The journey through Italy of museums to discover fantastic animals and places comes to stop number eight,Emilia Romagna. As usual, many fantastic creatures we found in the region’s museums, from the Apennines to the sea. Animals and Fantastic Places in Italian Museums is a project created by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture to help people discover our museums, safe places suitable for everyone, in a new way. Here are the animals from Emilia-Romagna!

Among the frescoes that decorate the walls of the nave of the Pomposa Abbey church is the “seven-headed beast” of which we find description in theApocalypse of John (13:1:11): “And I saw a beast come up out of the sea, which had ten horns and seven heads, on the horns ten diadems, and on each head a blasphemous title. And I saw another beast coming up from the earth. And it had two horns like the horns of the lamb, and it spoke like a dragon.” The artist, a painter of the Bolognese school who worked in the mid-14th century, depicts her just as she comes out of the sea, among the fish. We see her depicted as a leopard-bodied animal with dragon heads, and with a diadem over each of the heads, as per the Johannine description: she tends to be interpreted as a symbol of Satan. Its presence is particularly significant in that it is an interesting example of the figurative and religious language of the medieval period, which is located here as part of a cycle of frescoes with New Testament stories, of which theApocalypse of John is a part.

The image of Saint George Slaying the Dragon by Vitale degli Equi (Bologna, c. 1310 - 1360), a work preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, is one of the most famous in the history of medieval art. We do not know where this painting came from, but it is one of the most interesting attestations of the very lively, almost expressionistic language of Vitale degli Equi, also known as Vitale da Bologna (on the thigh of the horse we see a monogram that has been interpreted as his signature). Legend has it that St. George saved the princess of Selem from the clutches of a terrible dragon who wanted to devour her, as she was offered as a sacrifice by the people of Selem to appease the animal’s voracity: we see here the saint engaging in a fierce struggle, in which the horse caught in a loud neighing that we almost seem to hear, against the monstrous beast about to be overpowered by St. George’s lance. The princess, with noble features, watches the scene further back, sheltered. For the great Roberto Longhi, Vitale degli Equi’s painting is like a “fable between arcane and savage enough to anticipate the heteroclite follies of so many Nordic masters, from the Bohemians of the 14th century to Matthias Grünewald.” And we can also consider it one of the most dramatic and intense works in medieval art history.

The Bologna museum also holds one of Parmigianino’s (Parma, 1503 - Casalmaggiore, 1540) finest masterpieces, the Santa Margherita Altarpiece, so called from the presence of the saint. Legend has it that this saint, originally from the city of Antioch, was denounced as a Christian by the prefect Ollarios, who tried to seduce her but was rejected by her, and therefore decided to punish her. While in prison, Margaret was visited by the devil, who took the form of a terrible dragon: she was able to drive him out, however, by the power of prayer alone. In Parmigianino’s painting, we see the dragon painted as a hideous being, at once resembling a reptile and a fish, with its mouth wide open, below the saint who tenderly approaches the Child Jesus to receive a kiss from him to seal their mystical union. It is one of three altarpieces that Parmigianino painted during his stay in Bologna, between 1527 and 1530. “A masterpiece of the Italian manner” (as the scholar Jadranka Bentini has called it), the altarpiece was executed for the Benedictine nuns of the Santa Margherita convent (hence the subject matter), but was later given by them to the collector Giovanni Maria Giusti in exchange for a house with which they could expand the convent. Giusti, however, decided to destine it for the high altar of the convent church, where it remained until the Napoleonic requisitions: transferred in 1796 to Dijon, it returned to Bologna in 1818.

It is not often that we see fantastic animals in depictions of the episode of the Expulsion from Paradise: this is the moment when Adam and Eve are expelled from Eden because the woman is caught plucking the fruit of the forbidden tree. The Expulsion from Paradise by Jan Soens (’s-Hertogenbosch, 1547/1548 - Parma, 1611), a Dutch painter active in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (from 1575 and until 1606 he was court artist to the Farnese family in Parma and Piacenza), is distinguished by the presence of a unicorn: this presence is explained for several reasons. Meanwhile, the beauty of the animal, combined with that of the lush garden that serves as a backdrop to the story, serves to emphasize what Adam and Eve lost. Also, the unicorn in ancient times was a symbol of purity. And again, it was one of the Farnese family’s favorite heraldic animals: the family that ruled Parma and Piacenza thus wanted to allude to some extent to the splendor of their court by asking. We do not know where the painting was located; we do know, however, that it was part of a cycle entirely devoted to the book of Genesis.

Another unicorn that can be seen in Emilia Romagna is the one that appears in the elegant decorations of Casa Romei in Ferrara, and in particular in the wooden panels on the ceiling of the Sala delle Sibille. Casa Romei was the home built in the 15th century by the Ferrarese merchant and banker Giovanni Romei (1402-1483), who was very close to the d’Este family and the Ferrarese court, so much so that in his second marriage he married Polissena d’Este, niece of Marquis Borso d’Este. It is precisely to this marriage that the construction of the wing of Casa Romei where the Hall of the Sibyls is located is linked: the unicorn, a symbol of purity, is in this case a kind of homage to Borso d’Este, who had undertaken major reclamation of the marshy areas around Ferrara. Indeed, it was believed that the unicorn, a magical animal, purified the waters with its horn from the poisons they contained. Also completing the allegory of the Este land reclamation is the trellis behind the scene: in fact, it is reminiscent of the “paraduro,” or a palisade that was used as a support for river banks and to contain land for the purpose of filling in the canals to be reclaimed.

It is certainly one of the strangest fantastic animals to be found in Italian museums: a rampant lion with the head of an elephant. It is the heraldic symbol of the Del Sale family: the building in which it is located, Casa Minerbi, was in fact owned by the Del Sale family in ancient times. It is a residence of 14th-century origin but has been remodeled several times over time: the Hall of Coats of Arms, where the Del Sale family emblem is located, dates back to the second half of the 14th century. The Del Sale family had chosen to combine the two animals likely because of the characteristics that, according to medieval thinking, they symbolized: the lion was a symbol of strength, the elephant of prudence. Interestingly, the head is that of the elephant, demonstrating that it must still be the elephant’s prudence that drives the lion’s strength. Casa Minerbi is currently closed to the public, but it will soon be made accessible after major restoration work and a new exhibition layout.

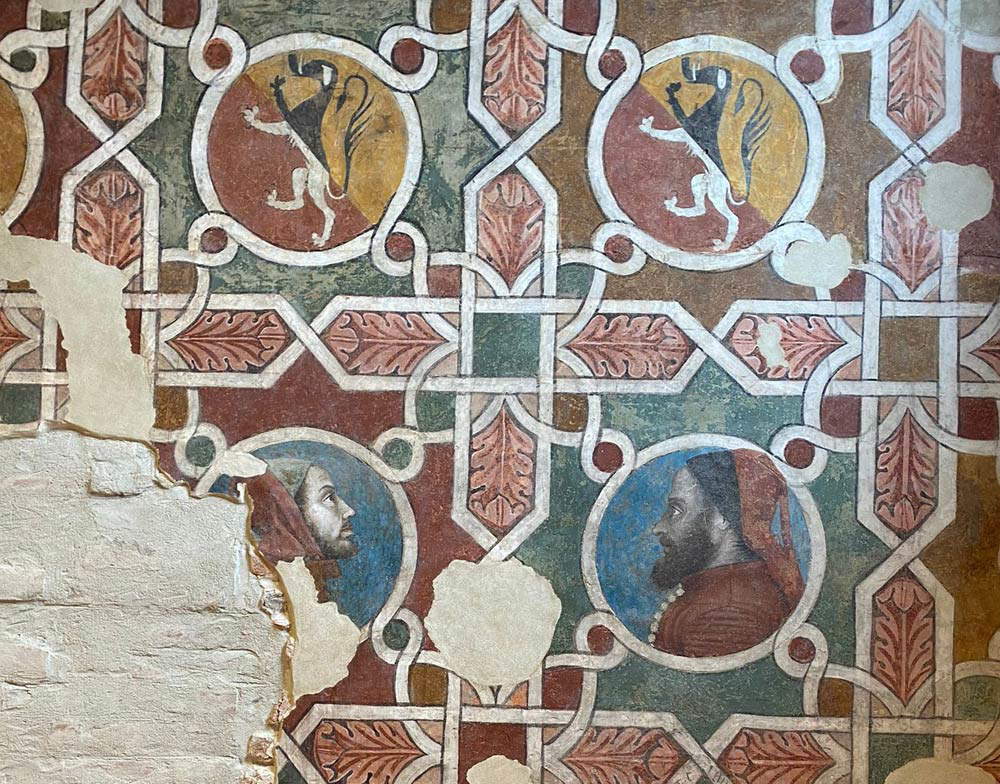

The Castle of Torrechiara, a splendid place nestled in the countryside on the far reaches of the Emilian Apennines near Langhirano, is a true paradise for lovers of fantastic animals: indeed, in the extremely rich decorations of the castle’s halls one can find all kinds of them. Few, however, are as present as the sphinxes: some can be seen in the Salone degli Stemmi, one of the richest and most interesting rooms in the building. This one also has a peculiarity: in addition to a woman’s head, it also features a female breast, demonstrating the imagination of the painter who executed it: the Mannerist culture, within which these frescoes were born, in fact loved the extravagant and the bizarre. The Hall of the Coats of Arms occupies the entire northeast side of the ground floor, and was in all likelihood the castle’s ceremonial space, where official receptions and even banquets were held. It is entirely decorated with grotesques: by this term was meant an ornamental motif on a typically white background and composed of bizarre interlacing of plants, animals and fantastic beings, which was very fashionable in the 16th century, and which owes its name to the fact that it was discovered in the Domus Aurea, the ancient residence of the Roman emperor Nero (these motifs were in fact widespread in the wall decoration of ancient Rome). Since the Domus Aurea was underground, the discoverers in the late 15th century thought they had entered a magnificent cave decorated in ancient times, hence the name of these motifs. We do not know to whom these frescoes are owed: the most likely name is Giovanni Antonio Paganino (active between 1572 and 1588), a painter who worked together with Cesare Baglioni, the “director” of the decorations of Torrechiara Castle.

The painting in question is the work of one of Ferrara’s leading artists of the second half of the 16th century, Ippolito Scarsella known as lo Scarsellino (Ferrara, c. 1550-c. 1620), and was made in pendant with another canvas depicting Original Sin. The protagonists of this pair of paintings are again Adam and Eve: here we see them in Limbo, where Jesus arrives to help the biblical Old Testament heroes ascend to Paradise by redeeming them from sin since they died before him, according to an episode described in the apocryphal gospel of Nicodemus. Eve approaches Jesus with folded hands, while Adam follows immediately behind. Surrounding them and the souls of those who died before Christ’s birth is a torment of devils, which Scarsellino’s imagination has allowed to be depicted in the most bizarre forms: there are some that look like dragons, the one on the right is a bizarre being with a very long nose, behind still we see one with an old man’s head and tail, and then the one in the center has a pig’s face, horns and claws, while behind him peeks out one that looks almost like a large rodent. This subject represents, to our knowledge, a unicum in Scarsellino’s production and is a relatively recent acquisition by the Galleria Estense in Modena, which bought it in 2000.

This frescoed fragment composes, along with eight other pieces, what remains of the decoration of a dressing room in the Rocca di Novellara, the former home of Alfonso Gonzaga, whose decorations were frescoed by an important local painter, Lelio Orsi (Novellara, 1508 - 1587), also known as Lelio da Novellara, one of the greatest Emilian artists of the 16th century. The subjects of the fresco cycle were taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and the one from which this laceration comes is certainly the bloodiest in that it depicts the flood that the god Jupiter hurled at humanity to punish it for its misdeeds. We then see humans wrestling with sea monsters in a tangle of bodies in the waves: among the fantastic animals are no shortage of hippocampi, creatures half horse and half fish. On the left, however, we see a figure hidden in a cloud from which a strong wind blows: it is Noto, the god of the southern wind. A curiosity: the background of these scenes is painted in mock mosaic, to imitate the decorations of ancient Rome.

According to legend, the minotaur was a hideous half-human, half-bull monster born of the bestial union between the queen of Crete, Pasiphae, wife of King Minos, and a white bull, which had been sent by the god Poseidon to Minos as a gift so that it could be sacrificed: the king, however, did not obey the sea god, deeming the animal too beautiful, so Poseidon as punishment made Pasiphae fall in love with the bull. The minotaur was relentlessly hungry, requiring the sacrifice of seven boys and seven girls each year to be fed to him: the hero Theseus offered himself in place of one of the young men and succeeded in killing the beast. In this columnar crater (a vase that was used to hold wine) from the Museum of the Ancient Delta in Comacchio we see the hero himself intent on defeating the monstrous animal. This is a vase that tells us the ancient history of this part of the region facing the Adriatic Sea: in fact, the ancient city of Spina, one of the main ports of northern Italy, stood here, where goods were constantly arriving from Greece, including figurative vases specially made in Athens and in Attic for the foreign market, just like this one, found in the necropolis of Valle Trebba and dating back to the fifth century B.C.

Attic potter

Attic potter |

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Emilia Romagna |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.