Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Abruzzo

The journey to discover fantastic animals in Italy’s museums reaches stage number seventeen: let’s find out today which creatures can be found in the museums ofAbruzzo. The project is conducted by Finestre sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and aims to help the public discover Italian museums, even the lesser-known ones, as safe and suitable places for everyone. Here is our itinerary in Abruzzo’s museums!

1. The dragons of the Marsica National Museum

The two dragons preserved at the Marsica Museum of Sacred Art in Celano come from the church of San Pietro di Massa d’Albe, from the hamlet of Alba Fucens to be exact. They decorate a panel bordered by a frame of stylized acanthus leaves. In medieval churches (the panel in fact dates back to the 12th century, and we do not know who the author is: the scholar Raffaello Delogu, former superintendent of L’Aquila, however, attributed them to artists who worked in collaboration with Roman masters) it is not uncommon to find representations of monstrous animals, which embody evil, or are used as demonic symbols, often defeated by saints. The uniqueness of this panel lies in the fact that the dragons, placed facing each other, have their necks entwined and entwined. We do not know the purpose of this tile, but it is likely to be a pluteus, or rectangular slab balustrade that was part of the ancient liturgical furnishings.

2. The dragon of the Church of San Pietro ad Oratorium in Capestrano

Another dragon is found on the portal of the church of San Pietro ad Oratorium in Capestrano: another 12th-century work, it responds to the idea that evil had to be left outside the church, which is why these monstrous presences appear on the facades of many churches of the time. The church in which this relief is located is that of the Benedictine abbey of San Pietro ad Oratorium, declared a national monument in 1902 and, as of 2014, managed by the Ministry of Culture through the Regional Directorate of Museums of Abruzzo. One of the singularities of the church lies in the fact that in the outer wall is a plaque with the “square of the Sator,” or the palindromic inscription, repeated on four sides, which reads “Rotas opera tenet arepo sator,” and whose meaning, despite several findings in various contexts, is still obscure.

3. The dragon of St. Michael at Casauria Abbey.

The dragon is also the animal that usually accompanies the iconography of St. Michael (when it is not replaced by the devil himself, although in this case we are dealing with more recent representations): and it is precisely in the act of defeating the devil that we see the saint depicted in a stone relief decorating a lunette in the abbey of San Clemente a Casauria, in the Pescara Valley. The archangel, shown with outstretched wings and dressed in a long tunic, is calm, almost smiling, and is caught piercing the monstrous animal with his spear. We do not know the artist who executed this relief, which, however, according to scholar Gloria Fossi appears to have been influenced by another master who worked in the church and who was distinguished by a refined technique, found especially in the folds of the cloaks and in the intensity of the gazes, characteristics that, moreover, we also find in this Saint Michael. The presence of St. Michael in this church is also due to the spread of the cult of St. Michael from not far away Monte Sant’Angelo on the Gargano, where he is said to have appeared in the late 5th century. The proximity to this place and the contacts that Abruzzi had with the Gargano and Puglia through pastoralism and the consequent transhumance were at the origin of the spread of the cult of St. Michael in Abruzzi. The peculiarity of this depiction lies in the fact that immediately below the saint we see depicted a galley, to which a psychopompa function was attributed, a term used to designate an entity destined to accompany the souls of the deceased. St. Michael, in fact, was believed to be a saint who accompanied souls to the afterlife, a function “inherited”; so to speak, from the god Mercury of pagan peoples.

4. The winged lion in Francesco da Montereale’s Madonna and Child with Saints at the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo

Made in 1505, this panel painting by Francesco da Montereale (Montereale, 1466 or 1475 - L’Aquila, 1541), one of the most important Abruzzi painters of the Renaissance, depicts the Madonna and Child, crowned by two little angels, with St. John and around the saints Catherine of Siena, Augustine, Lucy, Francis, John the Evangelist and Catherine of Alexandria. The painter is greatly influenced by Umbrian painting, particularly that of Pinturicchio from whom the figures derive, while the setting and sense of decorativism suggest that Francesco da Montereale must have looked to Carlo Crivelli. On the lower right we see a winged lion holding its paw above an open book: this is a clear reference to St. Mark the Evangelist, who is not present among the saints but is evoked by his symbol, precisely the winged lion, also called “St. Mark’s lion” or “Marcian lion.” St. Mark is represented with a lion because his Gospel opens with the words, referring to John the Baptist, “Voice of one crying out in the wilderness: prepare the way of the Lord, straighten his paths.” The voice of the Baptist crying out in the wilderness preaching baptism is likened to the roar of a lion: that is why the animal is associated with St. Mark.

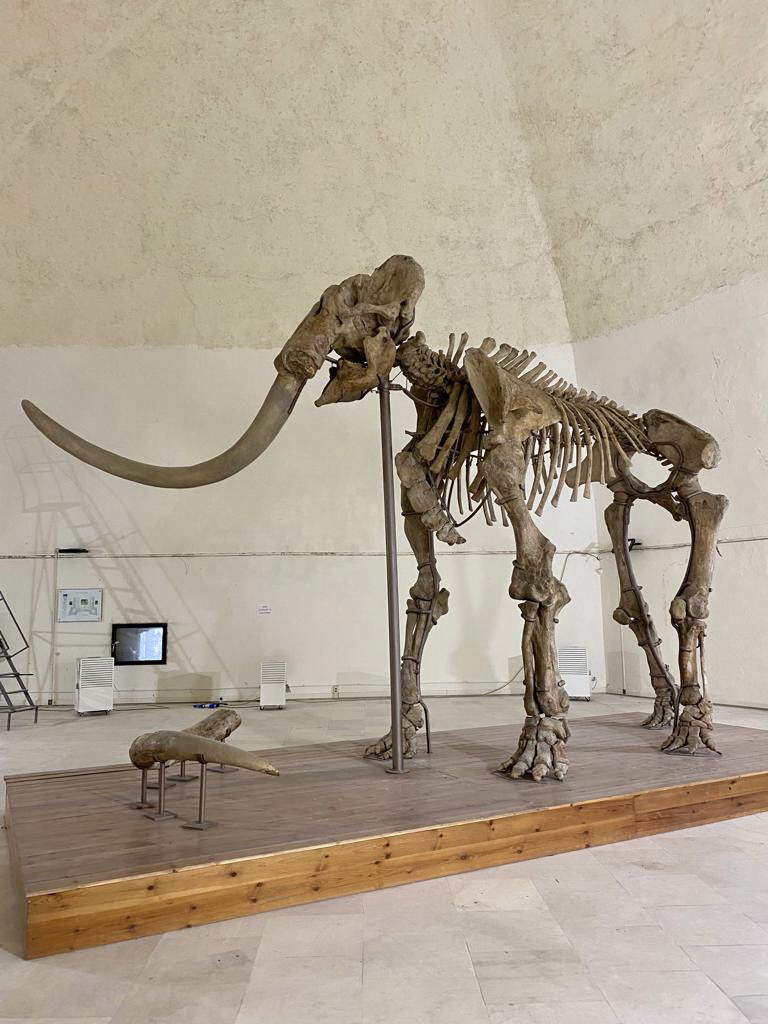

5. The Mammoth of the Abruzzo National Museum.

The mammoth is certainly not a fantastic animal, since it really existed, but because it went extinct in very ancient times, it evokes fantastic prehistoric imagery for us. And at the Abruzzo National Museum there is a skeleton of Mammuthus meridionalis, an ancient pachyderm native to lower Asia and also widespread in Italy at least until the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene (700,000 years ago). The animal could reach four meters in height and six meters in length, weighing about ten tons (that is, roughly the size of a present-day African elephant, although the tusks, as can be seen by looking at the Aquilan mammoth, were much longer: moreover, the southern mammoth had large molar teeth). The fossil in the Abruzzo National Museum was found in 1954 in a clay quarry near Scoppito, not far from L’Aquila: in 1960 it was displayed in the museum rooms at Spanish Fort, after which, following damage to the building during the 2009 earthquake, it returned to storage for restoration, and was again displayed to the public, with a new layout, in 2021.

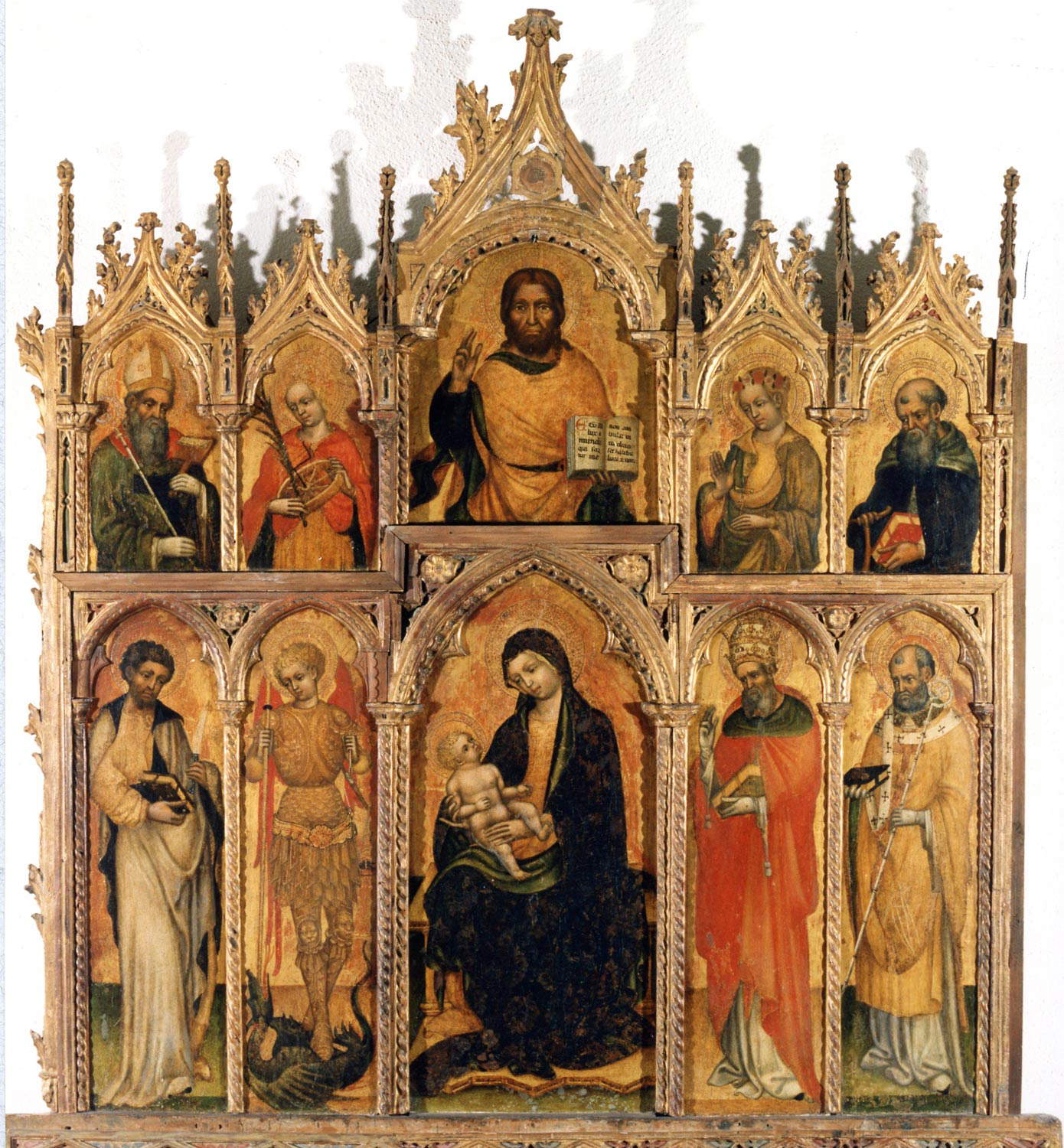

6. The dragon in Jacobello del Fiore’s polyptych at the National Museum of Abruzzo

Another Saint Michael with the dragon is the one we see depicted in the polyptych by Jacobello del Fiore (Venice, c. 1370 - 1439) kept in L’Aquila at the National Museum of Abruzzo. Jacobello del Fiore, a Venetian painter, was one of the most important painters of the Venetian school in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, although he spent much of his career outside his hometown. In Le Marche, his painting was mellowed by contact with the lesson of Gentile da Fabriano, after which the artist descended to Abruzzo, where he left several works, including this polyptych, one of the highest attestations of international Gothic in the lands bordering the Adriatic. It sees in the center the Madonna and Child and on the sides, in the lower register, Saints Bartholomew, Michael, Sylvester the Pope (or Gregory) and Nicholas of Bari, while in the upper register we find St. Blaise, St. Catherine of Alexandria, the Blessing Christ, St. Dorothea and St. Anthony Abbot. Discovered in a precarious condition by Enzo Carli in 1938, it has always raised important critical discussions since not all scholars agree on its authorship. What seems certain is that the splendid frame was made with the help of Abruzzi goldsmiths who innervated a flourishing tradition right at the end of the 14th century.

7. The devil in the polyptych of San Leonardo in Pianella at the National Museum of Abruzzo.

In this polyptych executed by Bernardino di Cola del Merlo (active between 1490 and 1500) and coming from the church of San Leonardo in Pianella (Pescara), the artist paints the figure of St. Michael as he defeats not the dragon as seen in previous depictions, but the devil, depicted as a monstrous, black being caught writhing under the saint’s spear. Despite the fact that this is a work made in the late 15th century, the setting is still that of Gothic polyptychs, but the author, in painting his figures, shows that he is up to date with the Perugian culture (of which he offers an obviously much cruder interpretation, being an artist of lesser quality), as shown especially by the figure of Saint Sebastian in the last compartment. The composition features the Madonna and Child in the center and on the sides a holy bishop, Saint Raphael, Saint Michael, and Saint Sebastian.

8. The animals on the plaque at the National Archaeological Museum in Campli.

At the National Archaeological Museum in Campli (Teramo) is preserved an ivory plaque, in the Orientalizing style, depicting a horse facing to the right, shown in the company of other animals, one standing above its back and two, on the other hand, standing below. It is a difficult work to decipher: it is not yet clear which animals are accompanying the horse. Moreover, the equine is shown with a very peculiar appearance: its tail, in fact, has the appearance of the head of an additional animal. Like almost all other materials on display at the Campli museum, this plaque was found in one of the tombs (specifically in the burial of a wealthy teenage girl) of the nearby Campovalano necropolis, which was only extensively excavated in the 1960s. This plaque is so distinctive that it has become the very symbol of the National Archaeological Museum in Campli: its workmanship proves that the ancient Picenes engaged in trade outside their territory, since the style of this work has no counterpart in the Picenian area.

9. The fantastic animals of the Campovalano sandals at the National Archaeological Museum of Villa Frigerj in Chieti.

The National Archaeological Museum of Villa Frigerj in Chieti preserves a very special object from the Campovalano necropolis: this is a pair of Etruscan-type bronze sandals, found in a female tomb, consisting of a shaped wooden top (now lost), made flexible with a jointed hinge halfway down the sole, which are tall and with the outer band decorated with mythological figures, fantastic creatures and real animals. In particular, the decoration features a mermaid with long hair, lion’s paws, tail, and fan-like wings (according to classical mythology, the mermaid was a half-woman, half-bird animal), depicted attacking a male figure, and then again a chimera, a panther attacking a wild boar, a horse with a female figure, some snakes, and a naked rider on horseback. This is a luxury item, decorated by a skilled craftsman, denoting membership in the hegemonic class of the woman to whom they belonged.

10. The hippocampus of the mosaics of ancient Teate.

Ancient Teate, corresponding to present-day Chieti, was one of the main centers of the Marrucini people, an Osco-Umbrian-speaking Italic population that fought against the Romans at the end of the 4th century B.C. and then allied themselves with the adversary by agreeing to be subordinate to the Romans: thanks to this move, however, they managed to obtain a certain autonomy for a few centuries, until their complete Romanization in the 1st century B.C. The city of Teate was then modernized: in the 2nd century AD a bathhouse was also built there, the floor mosaics of which have been preserved. As typical of all baths in ancient Rome, the baths of Teate also featured mosaic floors depicting marine animals, real or fantastic: the excellently preserved depiction of the great hippocampus is no exception. It was a legendary half-horse, half-fish creature that was often depicted in the processions of the god Poseidon. In the Theatine mosaic it is depicted, together with another identical hippocampus on the opposite side, along with another marine animal, a sort of dolphin.

The hippocampus

The hippocampus

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Abruzzo |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.