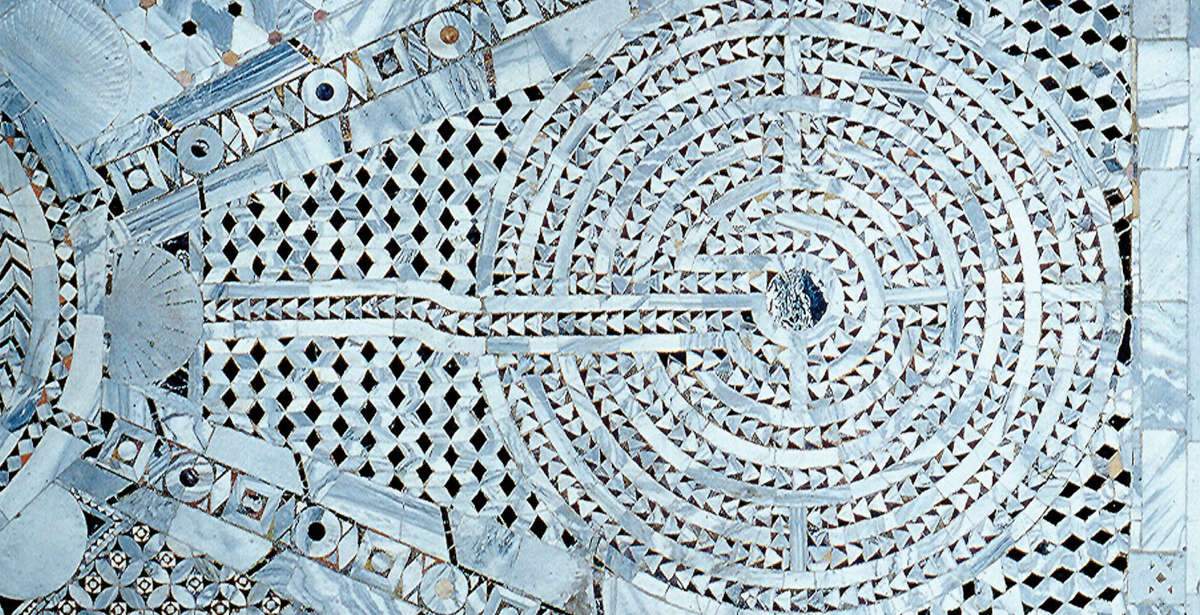

A marble labyrinth on the floor of the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.

It is of a predictable and disarming naturalness to find oneself wandering among the sights of Ravenna and carrying one’s nose upward, tangling one’s gaze among the golden mosaics until one arrives, more or less morbidly, at the highest point where the eye gets lost and confuses the tracks. But it is looking downward that one discovers equally interesting and faintly whispered secrets such as that of the labyrinth at the Basilica of San Vitale. “There is a labyrinth depicted on the floor in front of the altar,” Gustav Klimt wrote to his mother during one of the trips he took to Ravenna of all places: “it is a path of purification that leads to the center of the temple and when you walk through it it makes you feel lighter.” It was not only the opulence of the gold, then, that fascinated the Viennese artist, but also the geometric texture that unfurled beneath his feet.

It is an exercise that defies the keenness of sight as the basilica of San Vitale unmistakably represents an excellent work of an era marking the transition from Ostrogothic rule to the beginning of Byzantine rule in Italy, following the conclusion of the Gothic-Byzantine war. Its construction, inaugurated in 525, found its consecration in 547 under the auspices of Archbishop Maximian, and it fits distinctively into the Byzantine tradition, adopting an octagonal plan protected by a central core, surmounted by a majestic and delicate dome.The central core develops further in the chancel area, where the altar finds its location, culminating in an apse that embraces the Ravenna style, with an inner circular shape and a polygonal exterior. Despite its inception during the Ostrogothic period, under the protection of Theodoric and the financing of the renowned Ravenna banker Giuliano Argentario, the basilica reveals clear Byzantine influences, and this is not surprising, considering Ravenna’s deep ties with Byzantium since the time of Galla Placidia and Theodoric’s youthful experience as a hostage in Byzantium.

Diverging from the architectural approach of Roman and Romanesque structures, Byzantine constructions avoid massive masonry with mighty pillars, deep vaults and wide arches, but rather aim to communicate a feeling of lightness and elegance: the walls, perforated by windows allow light to filter in from all sides without creating sharp contrasts between illuminated areas and shadows, and the mosaics that adorn the walls, taking on hues from the vivid colors of the glass tesserae and the sparkling gold of the backgrounds.

Just inside the octagonal area, one discovers a fascinating pavement, where the observer’s gaze rests on the refined representation of the labyrinth with a circular shape that originates from the suggestive figure of a shell. With a diameter of almost three and a half meters, this iconographic motif became an integral part of the basilica after the renovation of the marble pavement strongly desired by the Benedictine monks of San Vitale between 1538 and 1545. The floor was redone not merely as a mere aesthetic affectation, but to raise the walking surface by 80 centimeters to try to counteract the frequent flooding caused by the gradual lowering of the entire religious building.

The elaborate renovation work legitimized the use of valuable ancient marbles, which found new life both in the complex labyrinth and in the sumptuous decoration of the basilica floor. Noble materials such as fine red porphyry, serpentine, antique yellow, fine Paragon black, fine Verona marble, and sumptuous red cipolin were carefully selected. The labyrinth, as well as the entire floor, were further embellished by the inclusion of vitreous pastes in vivid colors precisely delineating the circular path of isosceles triangles in white marble leading to the shell and further enriching it through the inclusion ofopus scutulatum: a background embellished with a refined perspective design of cubes.

All of this succeeds in leading the viewer to meditation as he or she tries to find the exit, but it is good to remember how behind the depiction of the unicursal Christian labyrinth there is no deception; rather, there emerges an awareness, both for those who venture inside and for those who walk the exit, that they can arrive at a dialogue with the divine. And so it is that vertical wall labyrinths, impassive and thus purely symbolic and evocative, together with floor labyrinths offer a viable alternative to physical travel and stand as a metaphor for pilgrimage understood as a means of salvation.

Beginning with the miniature Carolingian works of the ninth century, the labyrinth takes on an important Christian imprint by giving impetus to its tangible materialization within various Gothic-era buildings of worship. This metamorphosis underscores a gradual incorporation of labyrinth symbolism into the cultural and architectural fabric of the period, immersing its roots in a sophisticated iconographic tradition and thus manifesting itself as a symbol of convergence between the dichotomy of life and death, good and evil, rising as an emblem of the insatiable quest for some infinite time. Starting from the myth of Theseus, who triumphs through the rational determination of Ariadne, reaching the Baroque age that introduces the multicursal labyrinth, a symbol of the human capable of experimenting and master of his own destiny, moving to the Christian context in which Satan can be defeated solely through the power of faith in Christ, we discover how labyrinths are so intensely imbued with values and meanings that are similar to each other.

Since time immemorial, the labyrinth has embodied the risky complexity of the world, reflecting on life and death, good and evil, perdition and redemption: it stands as the supreme emblem of limitlessness that opens to a new dimension, yet to be explored for us finite and limited beings. Those who venture into or contemplate the labyrinth become aware that the boundary between human and divine, between finite and infinite, is mysteriously permeable, and it is no coincidence that its opening alone draws us irresistibly to the passage.

The labyrinth of the basilica of San Vitale, however, does not fall into the category of those that induce bewilderment, but the path that appears at the feet of the traveler is predefined and leads ineluctably from the shell to the heart of the plot. It thus appears as a symbol of pilgrimage of souls to the Holy Land, and its center embodies the final destination, the pinnacle of the intricate spiritual links with the divine, representing the culmination of the believer’s journey in which the shell is a synthesis of the pilgrimage.

|

| A marble labyrinth on the floor of the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.