The news, just a few days ago, is now well known: Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, has entered the UNESCO World Heritage List. And that was enough for handfuls of nostalgics to claim the achievement as a recognition bestowed on “fascist Asmara,” or “fascist architecture.” In reality, the footholds for talking about “fascist architecture,” or for reducing the artistic and architectural testimonies of colonial Asmara to the twentieth century alone, are rather precarious and flimsy: the Italian presence in Eritrea has a much longer history, and fascism represents but a single episode in this history that lasted decades and left traces that persist to this day.

To begin to clarify some aspects of Asmara’s urban planning, architecture and history, it is possible to start from the same definition that UNESCO gives of the city, namely “a modernist city in Africa”: therefore, we wanted to use a more inclusive reference, namely the term “modernist,” which, in international circles, identifies all the architectural styles that took turns in the course of Western art history between the late nineteenth century and the post-World War II period. In the description on the UNESCO website, it states the following: “positioned more than 2,000 meters above sea level, the capital of Eritrea developed from the 1890s onward as a military outpost of Italian colonial power. After 1935, Asmara underwent a large-scale urban planning program, with the application of the Italian Rationalist idiom of the time for government buildings, residential and commercial buildings, churches, mosques, synagogues, cinemas, hotels, etc. The site includes the area of the city resulting from the various planning phases between 1893 and 1941, as well as the unplanned indigenous neighborhoods of Arbate Asmera and Abbashawel. This is an outstanding example of early modernist urbanism in the early 20th century and its application in an African context.”

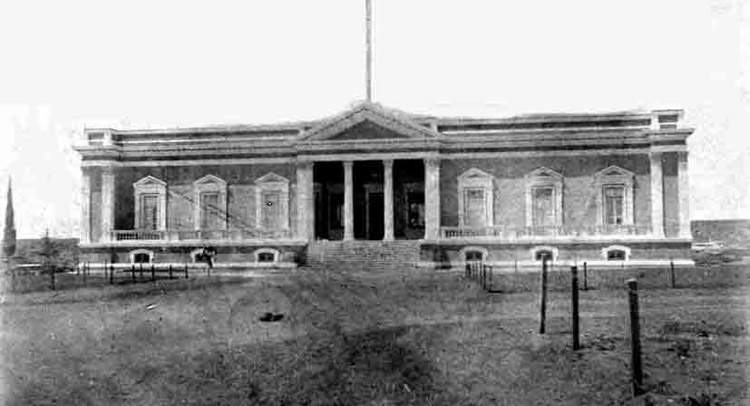

Not all of Asmara’s UNESCO-protected buildings were built during the period of Fascist occupation: there are several that date from earlier phases in the history of Italian colonialism. The Governor’s Palace, for example, was built in the neoclassical style in 1897, when the city had to prepare to welcome the seat of the Italian governorate, which, until then, had been located in Massawa. There are also many buildings dating back to the end of theGiolittian era, during which Asmara experienced rapid and intense development (certainly not comparable to what it had during the Fascist twenty-year period, but nonetheless the years immediately following World War I saw a number of construction sites spring up in the city). It is possible to mention two buildings that share the precise reference to a neo-Romanesque style that was particularly in vogue at the time: the first, in chronological order, is the Teatro dell’Opera, designed by Odoardo Cavagnari in 1918, and the second is the church of Nostra Signora del Rosario, begun in 1921 by Oreste Scanavini and finished in 1923. Also due to Cavagnari’s inspiration is the shrine of Degghi Selam, whose construction dates back to 1917, and probably also the facade of the cathedral of Enda Mariam, dating from 1920 but extensively remodeled in the fascist era.

|

| Asmara, the Governor’s Palace in a 1905 photo |

|

| Asmara, the church of Our Lady of the Rosary. Photo credit |

It is also true that the phase of major urban development took place during the years of Fascism (and Unesco itself declares this: in particular from 1935, the year that marked the beginning of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, an operation for which Asmara represented an outpost of exceptional importance), but this is not sufficient reason to speak of a “Fascist Asmara”: more correct, if anything, to speak of a “rationalist Asmara,” since most of the buildings constructed in the Eritrean capital during the Ventennio are connoted by the style that characterized much of the Italian architecture of the period. However, it is necessary to note that rationalism was born on the basis of cultural assumptions that had little to do with fascism. Take as an example the desire of the young architects of the period to draw on European taste as much as on the harmonies of classical Greece and the lines of the temples of the Mediterranean coasts: their ambition was to find a style based, in the first instance, on balance, rhythm, harmony. Nothing to do with the appeal to the imperial monumentalities to which the regime aspired in order to legitimize even from an artistic point of view its power. Consider, then, the fact that the architects of Group 7, who in fact sanctioned the birth of rationalism in Italy, drew on, albeit superficially and from a purely exterior point of view, the stylistic principles of a profoundly democratic movement devoted to full sharing such as that of the Bauhaus. And, moreover, it was precisely because of its open and innovative soul that the modern movement had great difficulty in spreading in Nazi Germany, which preferred in architecture a magniloquent, superb and exaggerated monumentalism of a classicist stamp. The latter also established itself to some extent in Italy, but in our country rationalism, during the Ventennio, did not encounter many obstacles in its path.

Unlike Nazism, Italian fascism was also moved by an innovative spirit, particularly evident in its desire to give the country a strong modernizing turn. The dictates of rationalism, which later inspired much of Fascism’s architectural works, were considered consonant with those of the regime, which in fact appropriated the movement, given also the lability of its ties with its European counterparts, to make it a political tool. The beginnings of Rationalism, moreover, were marked by a basic ambiguity: the aspiration to Mediterraneanism, and to an architecture with a European and international scope, ran the risk of giving way to obvious references to the so-called “Roman heritage,” as per the expression used in the contradictory essay by Adalberto Libera published in the catalog of the First Italian Exposition of Rational Architecture, held in Rome in 1928. In this text, considered one of the manifestos of Italian Rationalism, one can trace both the bases in common with the modern European movement (“Rational architecture-as we understand it-finds harmonies, rhythms, symmetries in the new building schemes , in the characters of the materials and in the perfect correspondence to the needs to which ledificio is destined”), as well as stances on the intrinsically national character of rationalism (“We Italians who devote our liveliest energies to this movement, feel that this is our architecture because ours is the Roman heritage of constructive power. And profoundly rational, utilitarian, industrial, has been the intimate characteristic of Roman architecture.”). This disagreement was masterfully captured, in 1933, by Edoardo Persico, an anti-fascist art critic found dead in 1936 in circumstances not yet fully clarified (he is thought to have been a victim of the regime’s repression), who spoke of an “inability” on the part of the theorists of rationalism “to rigorously pose the problem of the antithesis between national taste and European taste”: the consequence was the heavy risk of instrumentalization. And so it was, since Fascism took advantage of this ambiguity to resolve it in its own favor: prodromes of rationalism were identified, by regime intellectuals, in the architecture of imperial Rome, and Roman civilization was seen as the supreme model of that rationality from which the movement was inspired. Not only that, Group 7 wrote clearly that it did not want to break with tradition, because “it is tradition that transforms itself, takes on new aspects, under which few recognize it.” This aspect was also functional for fascism, which presented itself as a regime capable of welding modernity with tradition.

What is certain is that in Asmara, as well as in almost all Italian colonies, monumentalism struggled greatly to impose itself, because architects preferred to promote a more sober rationalism, which looked, yes, to ancient Rome, but more to domus and residential construction than to solemn and grandiose public architecture. In Asmara, colonial architects sought to construct buildings that were functional to the renewed needs of the population, and not buildings that celebrated the regime’s velleities of grandeur. Asmara’s architectures totally lack the celebratory vein that characterized many architectural works built in the Italy of the Ventennio. On the contrary: in Asmara there were also spaces for experimentation, and in this sense perhaps the most eloquent example is the Fiat Tagliero service station, a building that was designed and built in 1938 and is shaped like an airplane. A freedom that often distinguished Italian colonial architecture, as opposed to that of the motherland, which had to adhere to more stringent canons instead. An English engineer living in Asmara and author of several articles on Asmara architecture, Mike Street, described the city’s appearance this way in a 1998 essay: “people live in the center of the city, in stately or modest cottages, above stores or in apartments, in small hotels or family-run guesthouses. Whole neighborhoods of Art Deco villas are scattered all around the sunny hills. Cinemas, stores, factories, gas stations, offices, hospitals, churches, mosques and swimming pools have all been built in the same fresh, clean style. This is no longer fascist architecture, but Mediterranean-Modern in the mountains of Africa.”

In short, this is the heritage that UNESCO intends to protect in the capital of Eritrea: that of the “free gymnasium of Art Deco, futurist lines, modernism” (as defined by journalist Andrea Semplici), of the place where the most evolved styles of the twentieth century could be experimented with a certain freedom, of the city marked by the search for a classic and balanced geometry, of the site where the testimonies of an era that lasted decades are excellently preserved. And in all this, no room is discerned for the nostalgic.

|

| Asmara, the Fiat Tagliero service station. Photo credit. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.