It is almost 7 p.m. as I pass through the half-empty streets of the city. The new dpcm mandating the closure of theaters, cinemas and restaurants after 6 p.m. is already bringing its effects on urban sociality. The long shadow of the lockdown is increasingly tangiblejudging by the sound of the shutters dropping and the rhythm of the hurried footsteps of a few passersby.

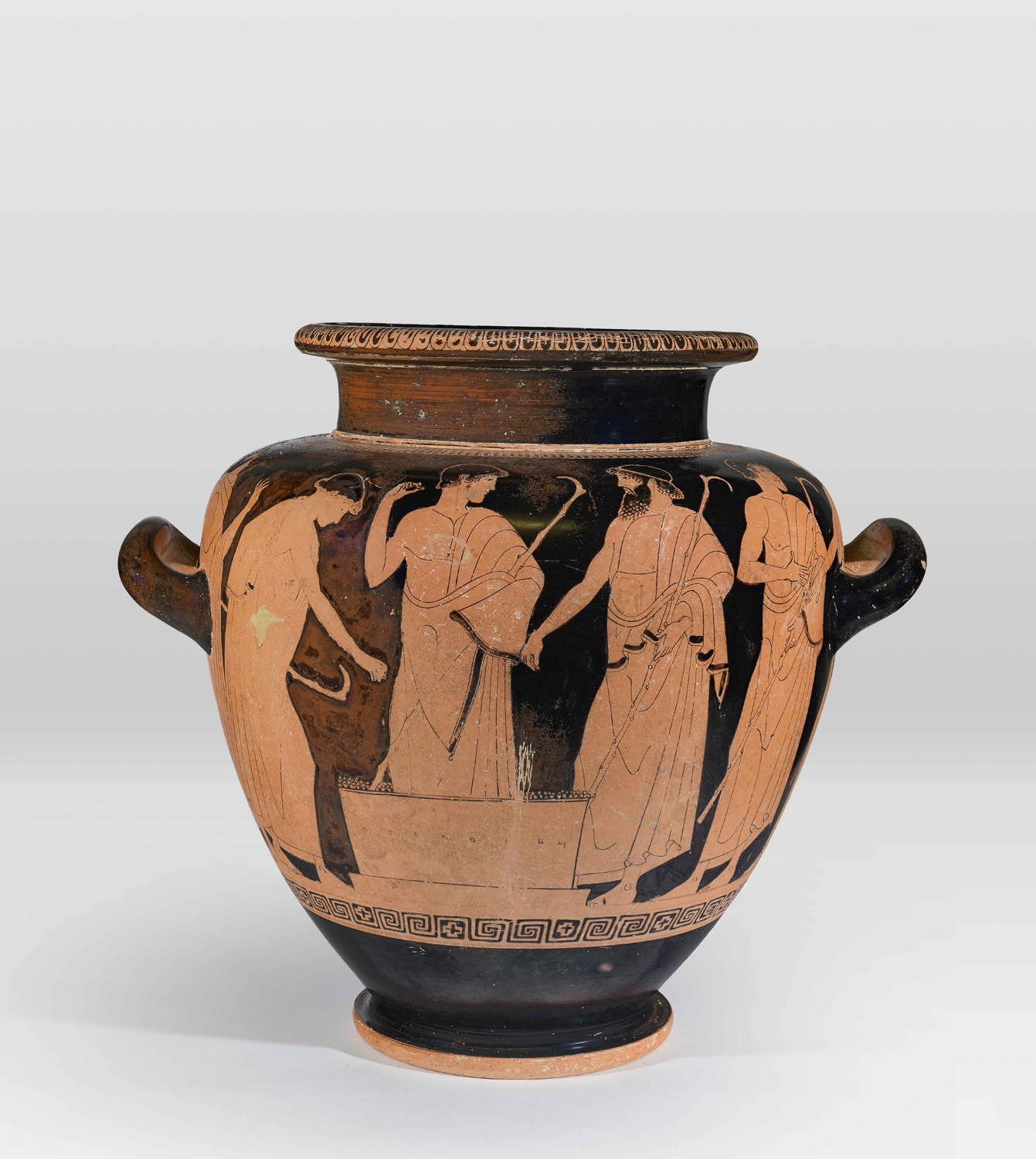

As soon as I enter the Archaeological Museum of Florence, however, I am greeted by a kind gentleman who measures the temperature while another worker hands out entrance tickets to other visitors who continue to arrive in a hurry. For a moment I feel as if I have entered an underground club, like those that were opened during the Prohibition era in America. Instead, I am at the opening of the exhibition Treasures from the Lands of Etruria. The Collection of Counts Passerini, Patricians of Florence and Cortona. A distinguished man in a suit and tie is emphatically recounting some passages from the Iliad in front of a beautiful Athenian stamnos (large vase) from 460 B.C. that reproduces the moment when the Achaeans democratically choose to whom they will hand over the late Achilles’ weapons. Around him dozens of appropriately spaced and masked people listen raptly. The guide is Mario Iozzo the director of the Archaeological Museum of Florence, who together with curator Maria Rosaria Luberto, an archaeologist from the Italian Archaeological School in Athens, has been welcoming for hours the many patrons who have come to learn about this precious collection. The various restrictions have already caused a sharp decline in visitors to Florentine museums. Seeing the people who are here is a pleasant surprise when we consider that archaeology in Florence has always had (unfairly) less visibility than the Renaissance narrative repurposed as a loop by major museum attractions.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Treasures from the Lands of Etruria. The Collection of the Counts Passerini, Patricians of Florence and Cortona at the National Archaeological Museum of Florence |

|

| Athenian red-figure Stamnos (symposium vase) (470-460 BC; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

|

| Figured lid of an Etruscan funerary urn made of fetid stone (second half of the 3rd-early 2nd century BC; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

|

| Etruscan funerary diadem |

As I enter I notice a section devoted to the maker of this true treasure. In the sepia-toned photo stands out in fine pose a bald man with a long beard; it is the portrait of a noted agronomist and botanist as well as one of the greatest collectors of the 19th century: Count Napoleone Passerini(Florence, 1862 - 1951). The son of wealthy landowner Pietro Passerini da Cortona, he devoted himself successfully to agricultural science, which led him to found the Agricultural Institute of Scandicci as well as distinguishing himself as a breeder of the finest Chianina breed. Thanks to his great economic affluence he was able to devote himself from a very young age to the growth of the family’s collection by sponsoring excavations and gradually acquiring new masterpieces. From the vast estates of Bettolle and Sinalunga and from the hill of Foiano della Chiana came the treasures of hundreds of Etruscan tombs with their magnificent grave goods. Some of these artifacts later found their way into the collections of the Metropolitan Museum in New York or the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Despite the dispersal of many artifacts, this valuable collection has also been supplemented recently thanks to the donation of numerous artifacts delivered to the Carabinieri Cultural Heritage Protection Command in Florence by a generous donor.

Among the many vases, jewelry and various utensils, I am struck by an Etruscan funerary diadem made of gold foil that is perfectly preserved and displayed in a dedicated showcase. Gold retains its characteristics even through the centuries and that is one of the reasons for its preciousness. The sketched face of the padded stand on which it rests prompts me to imagine that of the person who carried it. Perhaps he would never have imagined that his most beautiful jewel would be seen centuries later by other generations of men and women. She probably would not even have wanted it. Yet that tiara takes me back in time to the glories of the Etruscan age, and for a moment I forget the uncertain time in which we are living.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.