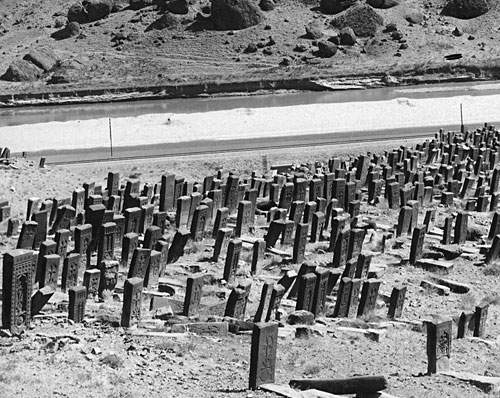

Last July 9, a long article, signed by political science researcher Simon Maghakyan, came out in Hyperallergic, calling the annual meeting ofUNESCO ’s World Heritage Committee (the committee that decides on sites that are part of, or will become part of, the World Heritage Site) an “insult to World Heritage.” Maghakyan’s very harsh stance against UNESCO is politically and culturally motivated: as is well known, the committee’s annual session was held in Baku, Azerbaijan, whose government is widely held responsible for what Maghakyan himself long ago deemed "the most serious cultural genocide of the 21st century." According to the researcher, over the past three decades Azerbaijan has wiped out much of the cultural heritage of Armenians in the country: a massive destruction operation that, in scope, would surpass even that carried out by Isis in Syria and Iraq. Symbolic of this campaign is the ancient city of Julfa, which until not long ago housed a medieval cemetery with the largest existing collection of khachkars (the typical Armenian funerary stele, usually densely decorated with elaborate ornamental motifs and with a cross in the center: since 2010, the khachkars have been part of UNESCO’s Intangible Heritage). Between 1998 and 2006, the site was deliberately destroyed (“the 1,500-year-old cemetery,” Icomos pointed out in 2006, “was completely razed to the ground”), and there are photographs and videos that can provide evidence of the devastation. According to the Azerbaijani government, there would be no destruction: simply, the monuments whose disappearance many lament would never exist.

Maghakyan pointed the finger at UNESCO, saying that not only has the world organization charged with the protection of culture not opened its mouth to publicly condemn the destruction of Armenian heritage in Azerbaijan (a country in which, it should be specified, anti-Armenian sentiment is strong and persistent, and Armenians are, according to a report by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, “the most vulnerable group in Azerbaijan when it comes to racism and racial discrimination”), but which has also gone so far as to describe Azerbaijan as a “land of tolerance.” Underlying the collaboration between UNESCO and Azerbaijan, Maghakyan denounces, would be economic motivations, including a $5 million donation that Azerbaijan granted to UNESCO in 2013. But while it is true that UNESCO does not receive adequate funding, it is equally true that it should not tie itself too closely to its donors. “One could argue about whether or not it is right for UNESCO to sever all ties with a country that has based its wealth on oil and destroyed 28,000 monuments,” Maghakyan concluded, “but to have hosted the world’s leading meeting on heritage conservation is a kind of point of no return: and UNESCO’s cruel irony in hosting the annual session of the World Heritage Committee is nothing less than an insult to all of the world’s heritage.”

|

| Julfa cemetery in a 1915 photo |

|

| Khachkar in the cemetery of Noraduz (Armenia) |

|

| UNESCO headquarters in Paris |

But it is not just the Azerbaijan problem that holds sway. Less serious, but still pressing, are the issues specifically affecting our country. UNESCO has not done much to save Venice from the problems of mass tourism: it could have inscribed the lagoon city in the sites at risk (the damage, and potential damage, caused by cruise ships in transit through the Giudecca Canal and beyond is news in recent weeks), while at the same time achieving two good results, namely making official the risk situation facing the city, and opening a discussion on what weapons UNESCO has at its disposal to deal with new problems that have arisen in recent years, such as those arising from the phenomenon ofovertourism. Journalist Anna Somers Cocks, founder of The Art Newspaper and past president for twelve years of the Venice in Peril association, has in recent days wondered “what UNESCO can do,” if “it has become so fearless and hopeless in defending its sites, and if it fails to recognize the obvious fact that Venice is in danger.”

And again, fierce controversy has arisen around the nomination of Italy’s fifty-fifth World Heritage site, the Prosecco Hills: the hills around Conegliano and Valdobbiadene, famous worldwide for their wine production, are, according to a study by the University of Padua, subject to a high risk of erosion, linked to intensive plowing, soil compaction, herbicides used in cultivation, and the fact that fragile hillsides are also being cultivated. And the situation worsens year by year, as the intensive cultivation of vines whose grapes will be turned into prosecco spreads at the expense of other types of crops, engulfing forests and meadows. What would be needed in this case, according to Massimo De Marchi, an expert in territorial and environmental policies and professor of Environmental Assessment Methods at the University of Padua, is a reflection “on the model of agriculture we are proposing”: an agroecological plan is missing in Italy and our country lags behind Europe in thinking about “what it means to think about production that feeds hundreds of millions of European citizens only with an agroecological model.”

|

| A cruise ship transits the Giudecca Canal in Venice. Ph. Credit VVox |

|

| Image of theVenice incident on June 2 |

|

| Crowd in St. Mark’s Square in Venice. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Protest against large ships in Venice. Ph. Credit Comitato No Grandi Navi |

|

| The Prosecco Hills |

Already last March, environmental associations had launched a protest march against the UNESCO candidacy of the Prosecco Hills, pointing out how vines for the industrial production of prosecco have totally disrupted the hills (with earthworks and deforestation), massively modifying a landscape that today looks totally different from what it looked like even just ten years ago, how prosecco monoculture has led to the disappearance of about half of the area’s bird species, how the crops are the source of the hydrogeological dangers that continuous earthworks create for the inhabitants, and how the extensive use of pesticides promotes pollution. Moreover, it was only a few days ago news that a group of citizens of Miane, near Treviso, protested against the clearing of a hill that is to accommodate a new vineyard (the inhabitants fear, as just mentioned, risks to the hydrogeological stability of the place and to the health of those living in the area). UNESCO, in essence, seems to have listed a site that perhaps should already be listed as endangered.

When a site is listed as a World Heritage Site, it is almost natural to associate the recognition with the benefits it could bring for tourism, or to consider it, as one would think from scrolling through politicians’ statements about the Prosecco Hills, a sort of certificate to excellence: yet World Heritage was not created as a tourist stamp, but as a list of sites to be protected and preserved with the utmost care so that they reach future generations as we inherited them. “Cultural and natural heritage,” reads the organization’s official guidelines, “is a priceless and irreplaceable resource not only for individual nations, but for all humanity. The loss, through deterioration or disappearance, of any of these precious resources constitutes an impoverishment of the heritage of all the peoples of the world. Parts of this heritage, because of their exceptional qualities, may be considered of ’extraordinary universal value,’ and are therefore worthy of special protection against the dangers that increasingly threaten them.”

Is UNESCO still able to live up to these guidelines? The answer, of course, can only be yes, but perhaps it is time for the organization to begin to reconsider itself and change its working systems: revise certain political ties (the case of Azerbaijan is emblematic), lighten its bureaucratization, reconsider the criteria for awarding recognition if it is true that there are too many sites and if it is true that, on the contrary, many noteworthy monuments are still excluded (on July 16, journalist Oliver Smith, in an article in the Telegraph wryly pointed out that the World Heritage Site also includes “a meat-packing plant in Uruguay, a shoe factory in Germany, and a hydraulic elevator in Belgium”), making more stringent commitments in assessing endangered sites, exerting stronger pressure on the countries in which these sites are located could be actions to be taken in the future. In a fervent article published last July 10 in The Art Newspaper and devoted to UNESCO’s failure to protect Venice at the Baku meeting, Francesco Bandarin, former director of UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre, wondered whether “anything can be done to make the World Heritage Committee stop being a marketplace for the exchange of favors between nations and return to what it was when the 1972 World Heritage Convention was signed.” That is what more and more observers are beginning to wonder.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.