The petition against Balthus is an act of imbecile violence, but the issue to think about is a different one

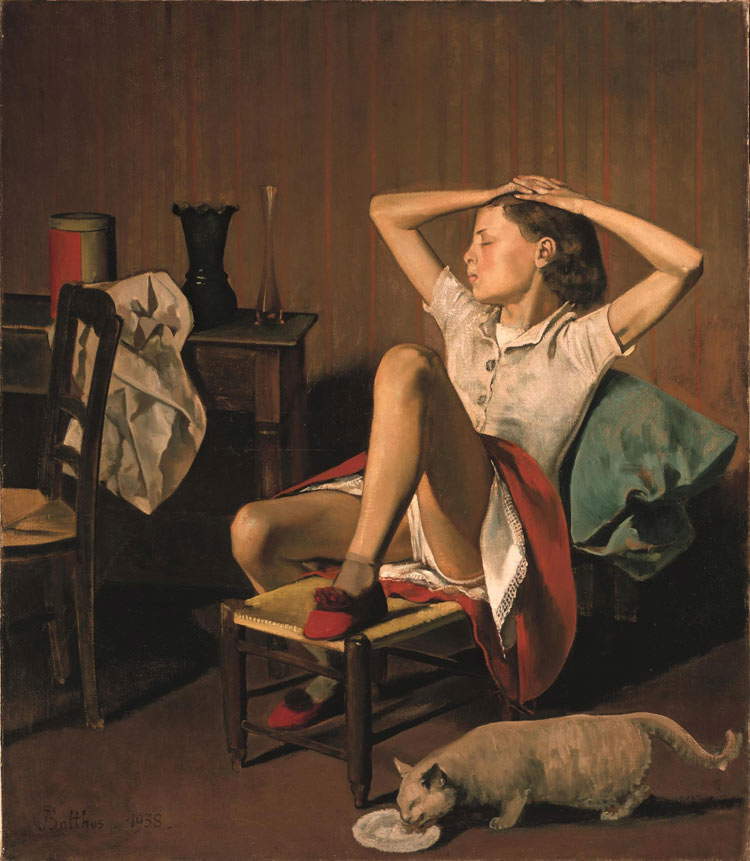

The article you are about to read is the result of long reflection. Not so much on the content, for that would have sprung up almost on the spur of the moment, as on whether or not to publish it: In fact, before doing so, we wondered whether it might not have been better to let the news of the online petition launched by a certain Mia Merrill, a New York City resident who is in fact asking her city’s main museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to take action to stigmatize the content of a painting by Balthus (Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001), known as Thérèse Dreaming and depicting a 12-year-old girl, Thérèse Blanchard, sitting on a chair in a disheveled pose that reveals her panties to the viewer. In the petition, the work is passed off as a painting that “romanticizes the sexualization of a little girl.” We read that “it is disturbing that the Met can proudly display such an image,” that “the Met, perhaps unwittingly, supports voyeurism and the reduction of children to objects,” and that “there is no call to censor, destroy, or never show the painting again, but to seriously consider the implications of displaying certain works of art on the walls of the Met, and to be more conscientious in contextualizing certain works to the masses.”

|

| Balthus, Thérèse Dreaming (1938; oil on canvas, 149.9 x 129.5 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

It is necessary to consider the petition for what to all intents and purposes it represents: an act of imbecilic violence, an obscurantist, arrogant, ignorant and bigoted demand, the child of a retrograde puritanism but brought back into vogue by the muddling excess of political correctness that now seems to permeate every debate and discussion. Thus, aware that silence is the best response against those in search of easy visibility, we had wondered whether we should give the news no weight. Especially since the Met has rightly responded, through the press office, that it has no intention of removing the painting or changing the context in which it is displayed. And also because, when all is said and done, the supporters of the petition seem to make up the numbers since there are ten thousand of them, but compared to the rest of the civil society they represent a sparse and negligible minority, immediately swamped and silenced by the shower of condemnatory articles that appeared in all the newspapers of the world and negative comments from thousands and thousands of users of online newspapers and social networks. But then we also reflected on the Met’s consideration that “moments such as these provide an opportunity for discussion, and the visual arts are one of the most significant means we have for reflecting as much on the past as on the present and for encouraging the continued evolution of our culture through informed discussion and respect for creative expression.” Reflection, then, should focus not so much on the incommentable petition and the ridiculous vagueness of its drafters (because if the underlying assumption were valid, then we should denounce all curators of exhibitions on Caravaggio or Artemisia Gentileschi for incitement to crime), but on the delicate relationship between art, morality and censorship-a discussion that, unfortunately, never goes out of fashion.

Obviously, Ms. Merrill’s petition (who, moreover, as if the affair were not grotesque enough in itself, also studied art in college) will never be taken seriously by any person working in the field or aware that we live in the year 2017, yet we could almost consider it as the spectacular tip of the iceberg of more insidious and creeping but no less damaging manifestations of dissent against art: perhaps the most immediate and glaring example is that of the tribulations to which anyone wishing to post a Venus or any nude, modern or ancient, on Facebook is subjected.

As early as 1963, philosopher Rosario Assunto pointed out how any censorious velleity arises from that “ontological distraction” whereby the work of art is considered not as “a possible-irreal,” but as “a possible of which the reality we are experiencing, that is, the work of art, is the actual realization.” This ontological distraction entails, Assunto continued, two errors. The first is a moral one: the censors are unaware that by destroying, removing or mutilating the work of art, the message is not removed and the alleged injustice is not repaired. On the contrary: even very recent examples show how censorship has actually reinforced the message of the censored work. The second, on the other hand, is aesthetic: a possible but not real vice or injustice can make that dimension “procure an absolutely different, and indeed opposite, pleasure than the morbid complacency that a possible reality of those injustices, those crimes, those vices, that malpractice might arouse” (so many works that annoy the viewer are born precisely as works of denunciation). And the cause of this distraction is obviously one: the inability to understand the work of art. All the more so if one tends to apply the yardstick of the present to works of art of the past. All the worse if no effort is put into understanding the context within which the work of art originated.

It is quite normal for there to be works that may disturb the viewer, and it is equally normal to feel discomfort when confronted with a work of art. What is not normal is to call for actions against the work of art: it means attempting to impose one’s own morality, it is tantamount to wanting to forcefully make one’s own view prevail over someone else’s, it means nullifying any attempt at dialogue and progress. It means, in other words, opposing the work of art with a violent act. In essence: an action against art. Simply inconceivable in a modern society.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.