The media has a (big) problem with attribution in art

On May 14, at the Foreign Press Room at Palazzo Grazioli in Rome, a scholar of Renaissance art, Amel Olivares, told the journalists present that after an eight-year search, she had identified an alleged new work by Michelangelo, kept in a vault in Geneva: an oil-on-canvas reproduction of the Last Judgment from the Sistine Chapel, which would also be Michelangelo’s only oil-on-canvas work. The work closely resembles another reproduction of the Last Judgment, the one by Alessandro Allori: that is why, according to the scholar, Michelangelo, after making it, gave it to Allori to make a reproduction. For iconographic, stylistic, historical, and even logical reasons (in the absence of documentation to the contrary, it is much more plausible that the oil on canvas is a copy of Allori’s Judgment, and not vice versa) the reconstruction proposed by the scholar is entirely implausible. Yet, before some art historians, and this newspaper among others, explained in a few words the absurdity of the attribution, the news of a “new found Michelangelo” had been taken up by RaiNews, Ansa, Adnkronos and most of the national newspapers: all of them report only the version of those who proposed the attribution.

This is not the first time this has happened, far from it. Just over two months ago, several Italian and international newspapers reported a news first launched byAnsa in Trieste: the Italian heirs of the assassin of England’s King William II want to donate the triptych depicting the moment of the assassination to a major British museum. And they want to do so despite having received major offers from Saudi Arabia and the United States. The news bounces from newspaper to newspaper under the radar until it arrives in the Guardian, which has millions of readers: some of whom point out that the triptych stylistically cannot be from the 11th century, that many of the figures appear clearly reworked from the Bayeux tapestry (11th century, but became famous from the 19th century onward), and that some of the Latin phrases contain gross grammatical errors. The article is amended, but by then the news of the alleged medieval triptych was everywhere.

A little over a year ago, the discovery of a new Raphael had made equal noise: the “tondo de Brecy” was described not as a Victorian-era, as everyone thought, but precisely as a work by Raphael, an original. The result had been provided by an artificial intelligence, which had recognized as almost identical the tondo and the Sistine Madonna preserved in Dresden, of which the Brecy tondo is (or was thought to be) a copy. The story of the Ia that allows original paintings to be recognized was evidently considered so exciting that La Stampa ended up devoting a headline to it, writing in the opening of the piece, “now even in art Artificial Intelligence is making great strides wins a match against the homo sapiens super expert in art history.” But beyond the more or less enthusiastic tones, the attribution was taken for good a little by everyone, despite the fact that what was had was only software that recognized an original and a faithful copy as almost identical.

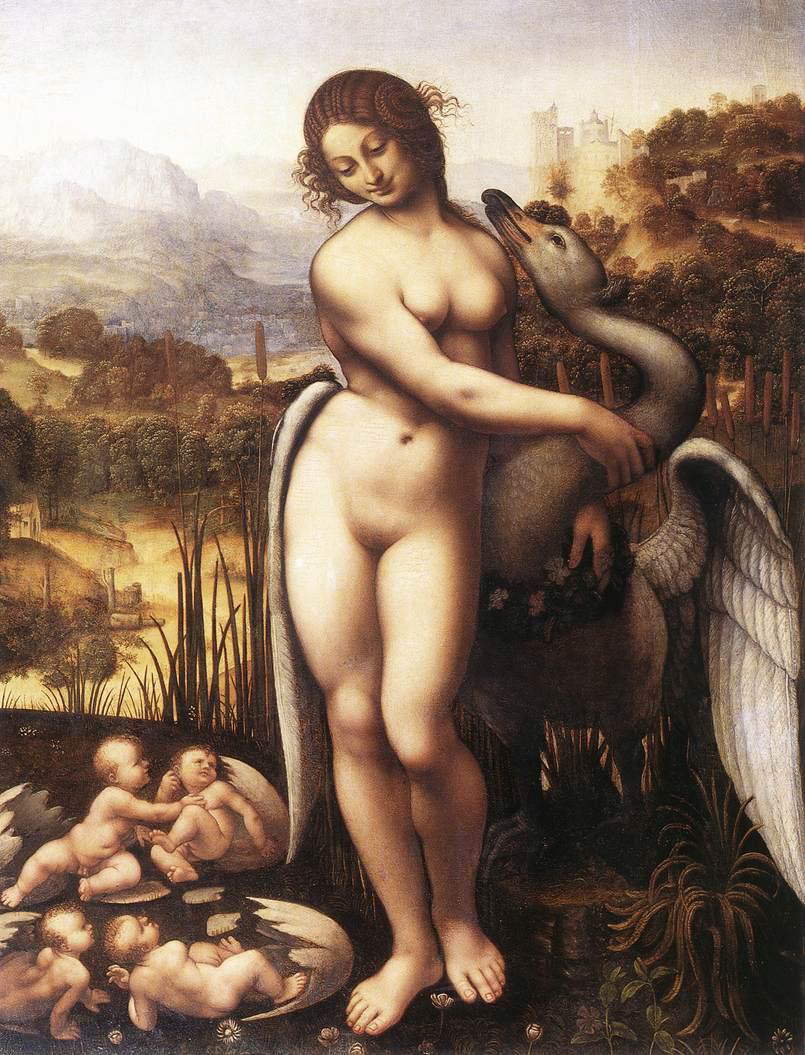

This pattern is constantly repeating itself. Just to mention a few recent cases, newspapers picked up the news of a new Raphael found (it was in all probability a copy from Perugino) in September 2023, then another in December 2023; a Leda and the Swan was attributed to Leonardo da Vinci in March 2023; then many other minor cases, with a debate about the second Mona Lisa continuing with more or less far-fetched proposals with constancy. It is nothing new that far-fetched attributions are being proposed; it has always happened. But instead, it seems to be increasing in the frequency with which these “wild shots” are taken at face value and revived by news sites with strong credibility, such as news agencies or national-level newspapers.

The pattern of these launches and relaunches is always similar: a news agency or daily newspaper picks up the news, without verifying it (i.e., without contacting one or more art historians who do not have private interests in the work), in this way legitimizing it, and other newspapers in the same way relaunch it, always reporting a single version, until - it happens rarely - someone with strong academic and media legitimacy claims that the attribution is at least improbable. Sometimes to tell the surprising new attribution to is a scholar in the field, who for the most varied reasons turns one of his hypotheses into a certainty; most often it is university professors (who derive authority from this aspect) from different backgrounds, often making instrumental use of scientific techniques that cannot be used to date or attribute: something, however, that the average public, including journalists, do not know.

Let me be clear, not all hypotheses of new attributions, even extraordinary and surprising ones, are of this kind. There are cases, even recent ones, where the hypothesis is both well-founded and debatable: for example, in the case of the Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo, a 16th-century level work that could actually be by Leonardo, or by a follower, or the Cimabue panel recognized in 2019 in a kitchen in France. There are various nuances in the art-historical debate. In all the cases we mentioned above, however, they are instead much more improbable hypotheses, sometimes surreal, sometimes technically impossible.

What leads them to end up in important and recognized newspapers is a dynamic, dangerous one, rooted above all in the crisis of journalism: in particular in the fact that, on the one hand, many journalists (most of them, even in news agencies) are paid per piece, or per pitch, and therefore little incentive to verify-a verification can blow up the pitch, and therefore the fee-and on the other hand that newsrooms are getting smaller and smaller, with fewer and fewer ordinary editors. Less knowledge, fewer contacts to call in case of doubt, more work. And furthermore, by a strange practice not only in Italy, those who tell in a biased or deliberately misleading way things that are not adequately verified or substantiated, in no way risk sanctions or lawsuits, if they concern the sciences, exact or not, unlike what happens in almost all other areas of journalism.

This weakness of the media system is often used, more or less legitimately, by people with private interests (the owners of the work, gallery owners, associates of the property). But it is also used, unfortunately, by public institutions, which “launch” partially false or misleading news counting on the fact that it will be difficult, or of little use, for editorial offices to verify it. In a dynamic that makes it increasingly difficult for readers who are not experts in the field to understand whether the news is verified or just told, creating confusion and contributing to polluting the debate.

A mistake many insiders make is thinking that certain “non-academic” news can be ignored. Victor Veronesi, an art historian from Milan who is engaged in systemic work of verifying and debunking press news, with disclosure on social media and information to journalists, has no doubts about this: “We cannot let these positions, which are rather difficult to prove in the absence of elements, circulate, clogging the media. They make life more difficult for journalists, who may not be able to understand when it is a real discovery, when it is a concluded research with scientific validity and when it is a hypothesis: this also damages scientific and critical research.” If all it takes to tell the story of art and increase the value of a work on the market is a good press office and a fair amount of rhetoric and imagination, it is a detriment first and foremost to those who are seriously concerned with the subject. Secondly, for those who want to know and understand it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.