“Territorial pissings” is not only the title of a famous song by Nirvana, but is also the expression with which Labranca identified pseudo-intellectuals who self-validate their positioning within a social area by marking its territory, that is, by criticizing or mocking situations or content deemed low or not worth mingling with. For example, those who emit indignant cries on social media when they hear about the Uffizi on TikTok. So many of those who cannot conceive of the presence of Italy’s most visited museum on a social full of videos of teenagers dancing in their bedrooms insist that it is “trivialization of art.” But trivialization is precisely what so many practice and seek. Otherwise they would not be standing in lines for yet another Banksy exhibition, otherwise they would not understand why museum “bookshops” are overflowing with books by Constantine D’Orazio, otherwise they would not explain why between yesterday and today the most visited page of our magazine was “we tried FaceApp on 15 famous works of art” (and surely it was also read by so many who are outraged by the TikTok videos in the Uffizi).

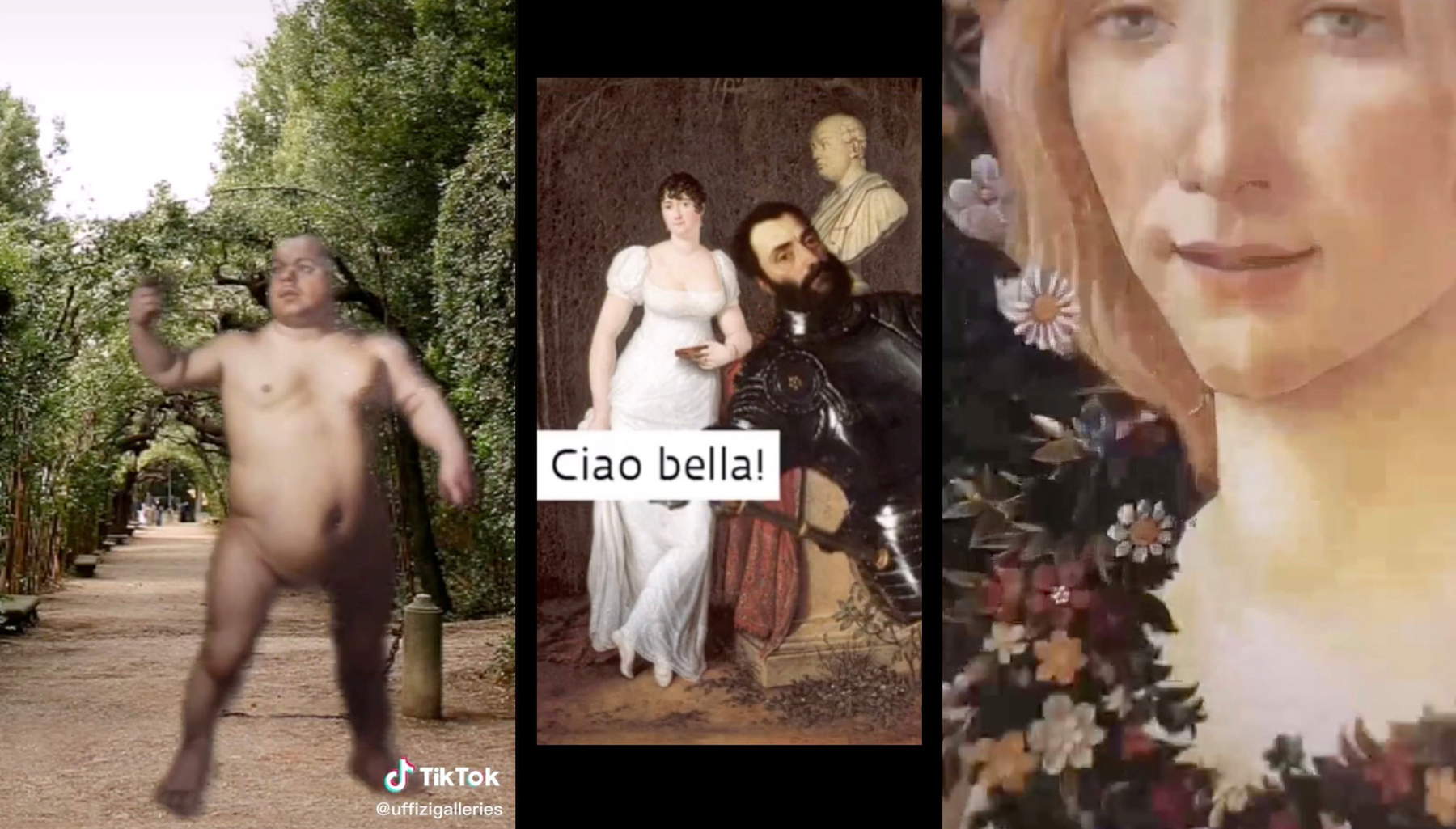

I am reminded of these considerations as I read in Repubblica a heartfelt intervention by Bonami who launches into an invective against the Uffizi’s antics on TikTok since, according to him, with such gimmicks, “art is removed from the public because it is reduced to a joke of the worst quality.” It escapes me what the mechanism is for which a video of the dwarf Morgante hunting to the notes of Blinding lights should prevent any attempt at further study, but there you have it: what is needed, says Bonami, “is respect for the work of art whose enjoyment by a vast public cannot be at the expense of enriching it. That is, the user must come out enriched by the artistic experience and not the other way around.” I am quoting Bonami’s exact words because, perhaps with different syntax or with the use of other synonyms, they are the ones most often heard uttered by a vast and varied congregation of our world’s denizens, from serious superintendency officials to the faint-hearted vestals who sequester their families on Sundays to take them to an FAI day or the Frida Kahlo exhibition.

|

| Dwarf Morgante on TikTok |

The data to focus on is: why should a stupid video exclude any “enrichment” a priori? To legitimize this idea is to have a really low regard for the public. Now, the Uffizi is visited every year by two million people, and I think we can agree that this is not an audience composed of two million Panofsky, Warburg and Wind who, in front of Botticelli’s Venus, engage in passionate discussions about the relationship between beauty, love and divinity in Neoplatonic philosophy. But neither are we talking about two million pithecanthropes who think that the “artistic experience” (if that’s what we have to talk about) stops at the dumb video on TikTok: any individual with an opposable thumb is perfectly aware that those videos are, as Bonami rightly points out, “jokes of the worst quality,” and no one imagines, even for a fraction of a second, that that is the upper limit they can expect to reach.

It is not the Uffizi antics of TikTok that rule out enrichment, because I think it is clear to everyone, even those who have never visited a museum in their lives, that that is an easy means of trying to expand the audience by seeking out new subgroups. The problems of enriching the experience, if anything, come later, when the audience enters the museum: they arrive when they see the latest pointless Van Gogh exhibition, where the poor Dutchman is presented as a suffering soul who painted moved almost by a spiritual afflatus and we forget about the social instances of his art, when we are confronted with a work by Caravaggio and the guides continue to peddle the inveterate cliché of the cursed painter without delving for example, into the political, religious and aesthetic bearing of his art, when they look at Banksy’s latest antics (punctually displayed in some Italian museum in search of easy queues) and think they know everything about street art. It is between these folds that the real trivializations creep in, fed by the generalist media that continue to present art to us as candy, as a mere aesthetic experience, as an alternative Sunday pastime to the trip to the lake. This cultural flattening, this leveling down, this encroaching aesthetic populism is infinitely more dangerous than a TikTok video, which itself was born as a low and crude product (and no one would dare to think otherwise).

Then, if for the TikTok user Caravaggio’s Medusa is simply going to be an interlude between the video of the guy dubbing his pit bull by engaging in an argument with him and the one of the little couple playing pranks on each other while ordering a hamburger at McDrive, the problem does not arise: it means there is no interest (which is entirely legitimate) and the Medusa will have slipped away among hundreds of videos of the same tenor that 15-year-olds from Houston to Romito Magra browse daily with the same compulsiveness. Just as the more palatial videos from the Prado or the Rijksmuseum offering pills about their works will have slipped away. And surely none of the TikTok kids will think of putting it down to authority or the sacred aura of the artwork. Smacking down the masterpiece, after all, is a genre that was not born on TikTok.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.