I believe that I am a person above parties and above suspicion when it comes to the movement of works of art : what speaks is the history of our magazine, it is the many battles we have always engaged in and supported to avoid unnecessary transfers, it is the personal convictions of myself and the editorial staff. In short, we are profoundly adamant that any movement should take place solely for scientific reasons, even if the work has to go only one floor of stairs. Of course, these are not original ideas: it is, in essence, what a great art historian, Francis Haskell, one of the most resolute opponents of the “mostrism” that has been raging for some forty years in most of those countries that also have a long tradition of art-historical studies behind them.

My positions have always been similar to those who, these days, are opposing the transfer of Caravaggio’s Seppellimento di santa Lucia, which should leave Syracuse to be displayed in an exhibition at the Mart in Rovereto. I have, however, always forced myself not to cross the line of extremism, that is, the one that many, on the matter of the Syracuse Caravaggio, have cheerfully crossed, often citing fanciful pretexts. It is necessary, in the meantime, to start from the curatorial project of Vittorio Sgarbi’s exhibition: the path imagined by the art historian, which I attempt to report below, rests on a series of historical and formal connections that bind the works that should be part of the project, namely Caravaggio’s Seppellimento and Flagellazione, a Grande ferro and a Cretto by Alberto Burri, and Cagnaccio’s Naufraghi di San Pietro. Summing up what Sgarbi told me, the exhibition will start with the intention of continuing the path to which the Mart gave birth in 2014, that is, to bring ancient art into a contemporary art museum: back then, a major exhibition on Antonello da Messina was organized, under the curatorship of Ferdinando Bologna and Federico De Melis, and today, six years later, it is intended to replicate that with this event on Caravaggio.

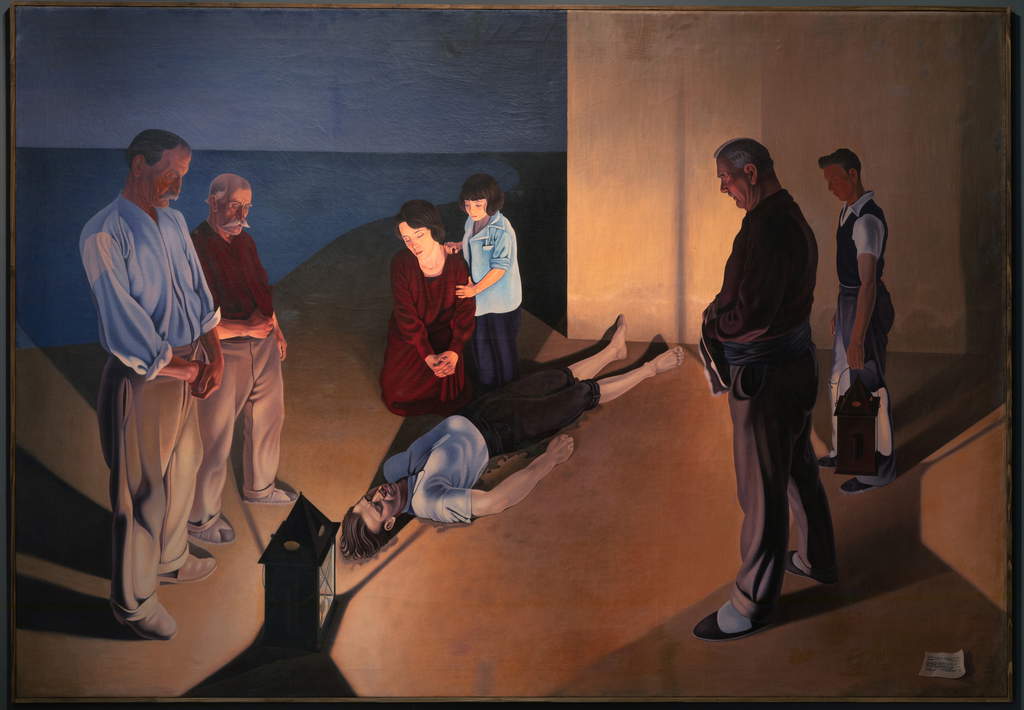

An exhibition event that aspires to reconstruct the relationship between Burri and Caravaggio (about whom, by the way, many have already written in the past: the names of Mauro Pratesi, Maurizio Calvesi, Bruno Corà come to mind) by evoking, through the presence of the Flagellation, a precise event, namely the entrance of the Grande Cretto, one of Burri’s most famous works, to the National Museum of Capodimonte: the Umbrian artist expressly wanted it near the paintings of the Caravaggeschi (it was 1978, the operation was strongly desired by Raffaello Causa and it was the first time that a contemporary work entered an ancient art museum: Sgarbi’s idea is to recall this passage). Then there is, as mentioned, the formal datum: the presence of the Seppellimento and the Grande ferro is aimed at bringing out the similarities between the two works, with the background of the Caravaggesque work highlighted as an anticipation of the informal of the second half of the twentieth century, and Burri (who, as is known, worked in Sicily) standing in direct figurative connection with the Caravaggesque precedent, in turn probably inspired by the natural landscape of the Ear of Dionysus just outside Syracuse. The Naufraghi, a work from the VAF collection on deposit at the Mart, where a figure that the project wants to connect to Caravaggio’s saint is at the center, instead has the task of introducing a reflection on Caravaggio’s realism and on the human types that crowd his art and that of his acolytes and that recall Pasolini’s Ragazzi di vita (Sgarbi has often emphasized the affinities, including physiognomic ones, between Pasolini’s characters and those of Caravaggio’s paintings: Pasolini himself, in the 1970s, had written some pages on the Lombard painter, and in particular on the realist and popular Caravaggio, referring to Longhi essays on Merisi).

|

| Caravaggio, Burial of St. Lucy (1608; oil on canvas, 408 x 300 cm; Syracuse, Santa Lucia alla Badia) |

|

| Michelangelo Merisi, Flagellation of Christ (1607; oil on canvas, 286 x 213 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, on deposit from the church of San Domenico, property of Fondo Edifici di Culto - Ministero dellInterno) |

|

| Alberto Burri, Large Iron (1961) |

|

| Alberto Burri, Great Cretto (1978; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) |

|

| Cagnaccio di San Pietro, Naufraghi (1934; VAF-Stiftung, on deposit at Mart in Rovereto) |

For the Mart, the confrontation between ancient and contemporary is nothing new: the formula of comparing a work of the past and one of the present is already part of the Rovereto museum’s offer, which a few months ago exhibited a Madonna by Bernardo Strozzi alongside a work by Yves Klein (after Caravaggio, this strand will continue with Raphael and Picasso, then with Canova and Mapplethorpe). This operation, although it intrigued me (to the point of going to the Mart to investigate: but I must also admit that Strozzi is one of my favorite painters), did not excite me all that much, just as, due to personal inclinations, I have little interest in the Burri-Caravaggio comparison, while recognizing that this is not a Sgarbi fetish, but is based on certain interpretative rivulets that have already emerged in the past from the pens of critics and art historians of unquestionable authority.

Now, the curatorial project may or may not be shared: it is certainly also legitimate to consider it fragile and weak, but that is not the point. The fact is that, in the meantime, the Strozzi and Klein exhibition was nonetheless an opportunity for scientific investigation, since the Genoese painter’s altarpiece, kept in a church in Tiarno di Sopra (near Trento), was restored during the exhibition: in the room of the Mart deputed to host the event (an enormous hall), the painting underwent a restoration that took place every day under the eyes of the public. Even if we want to consider the comparison with Klein as specious, the event offered the possibility of guaranteeing the work a necessary intervention (the altarpiece was in a far from good condition: it was clouded by dirt, it was altered by repainting and, above all, it had conspicuous falls and gaps), supervised by the superintendence and capable of leading scholars to discover some details of the work that were previously unknown. It was then also an important dissemination moment, since the public could see the restorers at work and ask them for any information or curiosity.

I think a question needs to be asked: what is more scientific than a restoration or a necessary conservation intervention? The same assumption also applies to the Burial of St. Lucy: the necessity of the intervention was stressed in the loan request to the Fondo Edifici di Culto del Ministero dell’Interno, the owner of the work, where it is stated that “the exhibition project has not only a valorization and research purpose, but also and above all a conservative one.” It is, moreover, the same ministerial directives that emphasize that the possibility of deepening the knowledge of a work and the opportunity to restore it should be relevant reasons for granting a loan. And here there is no doubt that the work has been, for years, in an execrable condition(we denounced its situation also on these pages, last year): it has been placed in a church (Santa Lucia alla Badia) that is not the place where it should be since the painting was moved in 2011 from the building for which it was made (the church of Santa Lucia extra Moenia) because the humidity of the latter risked compromising it permanently (and then because there were security problems), and what is more, in its current location, it is leaning against another painting, which therefore remains hidden from the eyes of the public. The Mart of Rovereto has made available the resources (350,000 euros) that will be used not only to finance a conservation intervention that is needed and cannot be postponed, but also to equip the work with a climabox, a burglar-proof case capable of guaranteeing the proper microclimatic conditions for the conservation of a work that, moreover, was last restored in the 1970s, by the Central Institute for Restoration in Rome.

Otherwise, the risk is to see the work permanently compromised: this is what art historian and journalist Silvia Mazza, who has kept the spotlight on the work for years on these pages, to the point of promoting in 2017 a conference on its status among the institutions involved, and who is now in charge of the technical coordination of the procedures inherent in the loan and conservation intervention for the Mart exhibition in Rovereto (the prodromes of the current project are to be sought precisely among the meshes of this long and constant interest), said in 2019 on these pages. And certainly, a museum cannot be expected to provide the funds to support the intervention on a work without being able to exhibit it: if for us the intervention comes before the exhibition, for the museum it is the exhibition that provides the occasion for the intervention (otherwise the museum would become a patronage association).

|

| The exhibition that compared Bernardo Strozzi and Yves Klein at the Mart in Rovereto. Photo by author |

|

| The exhibition that compared Bernardo Strozzi and Yves Klein at the Mart in Rovereto. Photo by author |

That conservation intervention is needed and is also rather urgent, we therefore wrote in Finestre sull’Arte already last year, but the situation of the work has been known for years (at least nine, if we take as a point of reference the date of the relocation of the Seppellimento from the church in the Borgata neighborhood to the one located in Piazza del Duomo): one would therefore wonder where the indefatigable defenders of Caravaggio were and what they have been dealing with until now. About the operation involving the Mart everything has been said. In order to keep the Seppellimento from leaving for Trentino, the most laughable and sterile arguments have been advanced: it has been said that only Caravaggio’s Sicilian works travel and that those kept in other churches have never been detached from their walls (when in fact it was enough to go and visit the great exhibition at Palazzo Reale in 2017 to see the Madonna of the Pilgrims, on loan from the church of Sant’Agostino in Rome, but not only that: the work had also gone on loan to Milan in 2006, and had returned damaged), the fusty cliché of the colonialist north stripping the south of its works was revived (when in fact, loads of works travel to and from every direction every day: to think that there is a fury against the south or against Sicily is simply to live outside of reality), the ability on the part of the Mart to allocate the 350,000 euro figure to the intervention was questioned on the simple basis of the fact that a regional ddl (and thus, being a ddl, still far from being approved) provides for cuts for the museum in Rovereto, there was regret that the Burial was not included in the list of immovable works of the Sicilian Region (when in fact the painting is owned by the Fec e, consequently, the Region has no say in moving it), there has been talk of “prostitution” of the painting in order to make it earn a restoration (when in fact, since the beginning of the world, fortunately there are patrons and supporters who finance restorations, and do not forget a Caravaggio in degradation, remembering it only when the possibility of moving it is threatened).

Then, as if that were not enough, the Sicilian section of Italia Nostra even claimed that the current location of the Burial in the church of Santa Lucia alla Badia “responds better to the needs of the community of reference,” also because the basilica of Santa Lucia extra Moenia “is a marginal place with respect to the historical city center and therefore extraneous to the main Syracuse tourist flows.” As if Caravaggio were a tourist promotion worker and the placement of a painting should respond to marketing reasons instead of cultural reasons: and if there is a possibility of having it stay in the church for which it was conceived, it is cultural reasons that should prevail. And there are also those who would like to musealize the painting: an anachronistic choice in 2020, when current technologies would allow us to avoid such translocations. It is then true that the church of Santa Lucia extra Moenia of today is no longer the one of 1608, but surely keeping the work where it was until 2011 (i.e., in its original context) would certainly be an infinitely less rash and arbitrary operation than locking it up in a museum, as well as a way to solidly tie Caravaggio to the Pasolinian context of the Borgata neighborhood, about which so much has already been written. Fortunately, however, there are also those who have defined the controversy as “sterile and useless”: this is the case of Legambiente Sicilia (so we are not talking about northern colonialists, but about an association of the territory, which has always been against useless loans), which has defined the “Caravaggio in Trentino” operation as “a serious project that can finally recover, restore and save the work, today in serious and certain danger,” and has branded as “provincial” those who “have created a useless fuss, seeking only publicity with easy slogans and useless alarmism.”

It is then true that the work is fragile (otherwise there would be no need for intervention: but it is also true that, for years, everyone forgot about it). It is also true that in recent years we have witnessed so many displacements that could have been avoided as unnecessary and often even harmful. We can then say that, as with most exhibitions, there is a probability that the “Caravaggio-Burri” exhibition will turn out to be anything but memorable. But more than a loan, we are de facto opposing a conservative intervention: the move will serve to make the operation possible, which, moreover, will take place in full view of everyone, just as it did for the Bernardo Strozzi altarpiece, about whose relocation no one in the Ledro Valley had any objections. And to oppose such an operation for reasons bordering on pure parochialism seems to me to risk causing serious damage to the work, since we will end up further postponing a necessary intervention, which will also serve to return the work to its church (an operation that, moreover, could be the prelude to the revitalization of the entire Borgata neighborhood).

Of course, we would all be happier if the work were to be restored in Syracuse, it goes without saying (even if the provision that the intervention, defined as “no longer procrastinable and otherwise unfundable” by the bishop of the Sicilian city, should take place under the high and close supervision of the Syracuse Superintendency goes in this direction). However, it does not seem to me that I have read so far of alternative projects: it would therefore be desirable that those who oppose the trip to Trentino should work just as hard to find the necessary funds for the intervention (in that case, we would have nothing to object to, indeed: only compliments will come from these columns). And, to complete the reasoning, it seems to me that no one is tearing their hair out over the departure of the Capodimonte Flagellation, a painting that has already traveled far and wide in recent years (including to useless exhibitions) and far more than the Burial, and a work that, moreover, would depart from a museum that, at least until the middle of the month, must already do without a very important nucleus of works, which left Naples at the beginning of the year to be exhibited in a superfluous and dastardly exhibition in Fort Worth in the United States (which, needless to say, we have obviously pointed out on these pages). However, if the displacement is someone else’s problem, then it’s all right (indeed, we exult): so what about the protection of the works only matters to us when the objects are within regional boundaries?

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.