On the triumph of aesthetic populism

In his seminal Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism begun in 1984, Fredric Jameson had summarized, with great clarity, the cultural trend that had been foreshadowed by MacDonald some twenty years earlier and that perhaps more than any other has characterized postmodernity: “the erasure of the boundary (essentially proper to advanced modernism) between high culture and so-called mass or commercial culture, and the emergence of new types of ’texts’ pervaded with the forms, categories and contents of that cultural industry so passionately denounced by all the ideologues of the modern.” Underlying this erasure is what Jameson sees as the supreme formal aspect of all postmodernism, namely that lack of depth(depthlessness) that would eliminate any hermeneutic possibility of the work of art and introduce a kind of surface culture, a necessary consequence of the reduction of art to a mere commodity and the separation of the work’s signifier and signified.

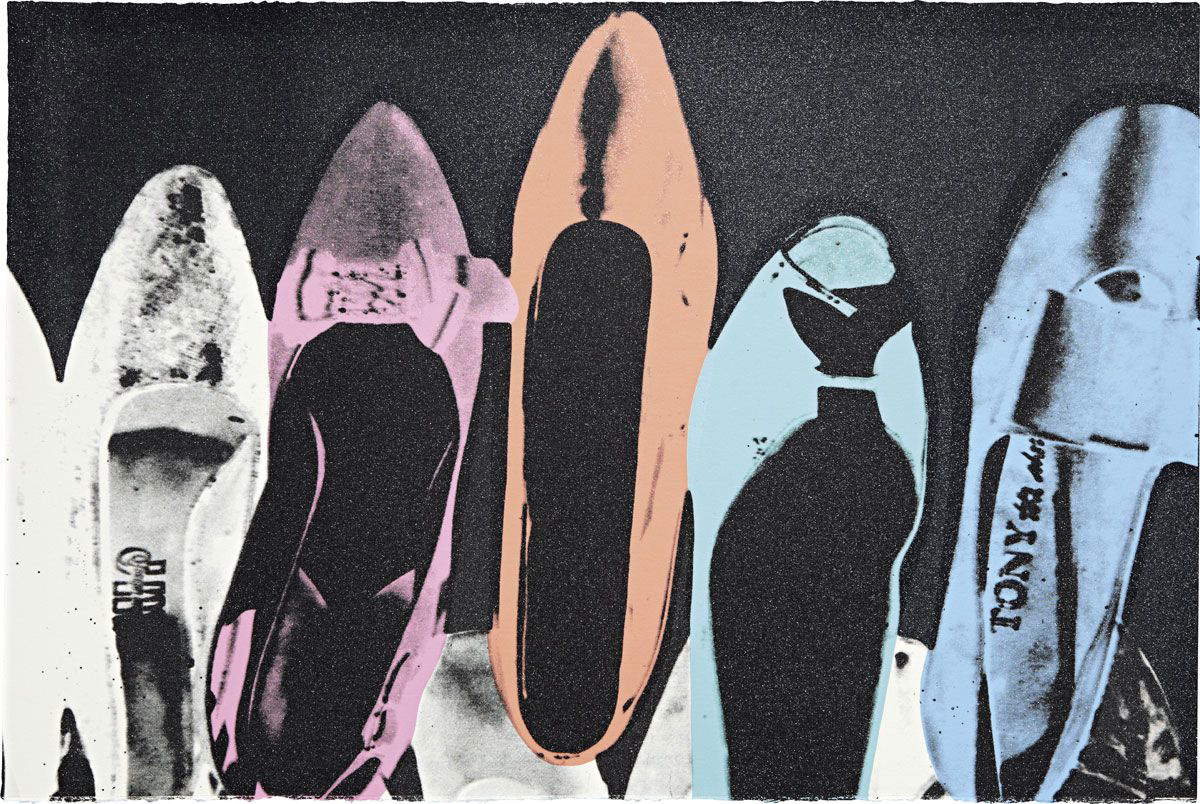

To better specify this concept of depthlessness, Jameson introduced the comparison between the “shoes” of Vincent van Gogh and those of Andy Warhol, calling into question the Dutch painter’s Pair of Shoes, painted in 1886 and preserved at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, and Warhol’s work Diamond dust shoes, from 1980. In the first case we are dealing with a work that, if it does not fall to the level of pure decoration, springs from a certain initial situation, which is set in a precise past and in a precise context: a context that needs to be reconstructed so that the painting does not remain an “inert object, a reified end product.” Jameson was calling into question Heidegger, for whom van Gogh’s shoes recreated the world that constituted its context, and were essence of that world, revealed to the concerning through the mediation of the work itself. A work that constitutes “a symbolic act” from the moment the image manifests itself to the eye of the beholder: the very materials, thick and coarse, that van Gogh used were a reflection of the strenuous peasant reality from which those shoes emerged, and the subsequent vangoghian explosion of the objects “in a hallucinatory surface of colors” was but a “utopian gesture, as an act of compensation that ends up generating a whole new utopian realm of the senses.” Warhol’s work, on the contrary, would present a mere “random collection of dead objects,” deprived of the ability to restore their lived experience: his shoes would be exclusively fetishes resulting from the commodification typical of contemporary society. In other words: Andy Warhol’s shoes, according to Jameson, do not speak, and it would not be possible to find in the image anything other than its mere signifier.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, A Pair of Shoes (1886; oil on canvas, 37.5 x 45.5 cm; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes (1980; ink and diamond dust print on paper, 101.6 x 152.4 cm; Private collection) |

Jameson had implicitly lumped together under the term “aesthetic populism” this attempt to eliminate the line separating high and mass culture, and a few years later, in his essay On “Cultural Studies,” he remarked how “the negative symptom of populism is the hatred and disgust with intellectuals as such (or with the academy, which seems to have become synonymous with them).” More than 30 years after their first formulations, Jameson’s theories on aesthetic populism not only seem extremely relevant, but also provide us with a basis for considering how this trend has taken hold and become increasingly aggressive, especially in our country, where one of the few to call attention to the issue in recent times was Gabriele Pedullà with an important article published in 2016 in Sole 24 Ore. The reason why Pedullà ’s voice can be considered substantially isolated is contained in his own words: characteristic of our days, Pedullà argues, is that aesthetic populism combines with political antipopulism giving rise to a phenomenon with unprecedented traits. It follows that those who “daily warn readers and voters against the threat of anti-system forces,” are the same ones who “miss no opportunity to grandstand the impatience of the most run-of-the-mill consumers toward any form of sophisticated art.” We are all, after all, familiar with many of the recent attacks on the intellectual class by so many politicians who claim to be anti-populist. There is thus a conviction that the people who should not be entrusted with decisions on the most important political issues, those who would not be able to inform themselves adequately and thoroughly before casting their vote in the voting booth, those often accused of being carried away by almost instinctive impulses or at any rate by logics that have more to do with emotion than with critical insight, can become, in matters of art, literature and music, the only admissible judge, against whom one cannot appeal.

This would not be a simple matter of taste, given the fact that taste has never been determined by the intellectual classes: it is a cultural tendency capable of undermining the very foundations of culture. And of such a tendency, to continue with Jameson’s examples, both van Gogh and Andy Warhol are victims (but the discourse could be extended to any representative of high culture): the former as totally decontextualized, deprived of the highest and deepest aspects of his art and his personal experience, the latter as overwhelmed by the very superficiality attributed to him. Aesthetic populism feeds on high culture (when in fact, before postmodernity, there was a popular culture that remained separate from high culture), but in doing so it corrodes it and deprives it of meaning: aesthetic populism, as a result, prevents us from looking at the figures of van Gogh and Warhol in their totality. And this is unprecedented, because if until not so long ago the “erasure of the boundary” was substantiated by a midcult production that imitated high culture without affecting it, now aesthetic populism directly wears down high culture: there has in essence been consummation of that degradation to pure decoration that Jameson feared. Thus, we have lost track of the fact that van Gogh’s works were endowed with disruptive and polemical social and political connotations, fueled by the numerous readings that had animated the great painter’s poetics (van Gogh was an avid reader: in his library could be found books by Michelet, Dickens, Hugo, Harriet Beecher-Stowe, and however much the artist read in no particular order or with no specific purpose, these were fundamental readings for the development of his painting). When confronted with Andy Warhol’s works, we do not question several fundamental aspects of his art (such as, for example, his relationship with religion), and we forget the fact that, if it is true as Barbara Rose argues, “Andy Warhol was a homegrown Duchamp who revived the Duchampian orientation of anti-art with intense proletarian vigor,” driven by the “Dadaist desire to change the rules of the art game so that more people could participate.” Aesthetic populism made van Gogh a tormented individual who painted propelled solely by his ineffable motions of the soul (a poor and trivializing interpretation officially sanctioned by the recent Vicenza exhibition, a markedly populist exposition), and Warhol the vacuous cantor of Hollywood celebrities, depicted in hundreds of replicated, easy-to-understand icons.

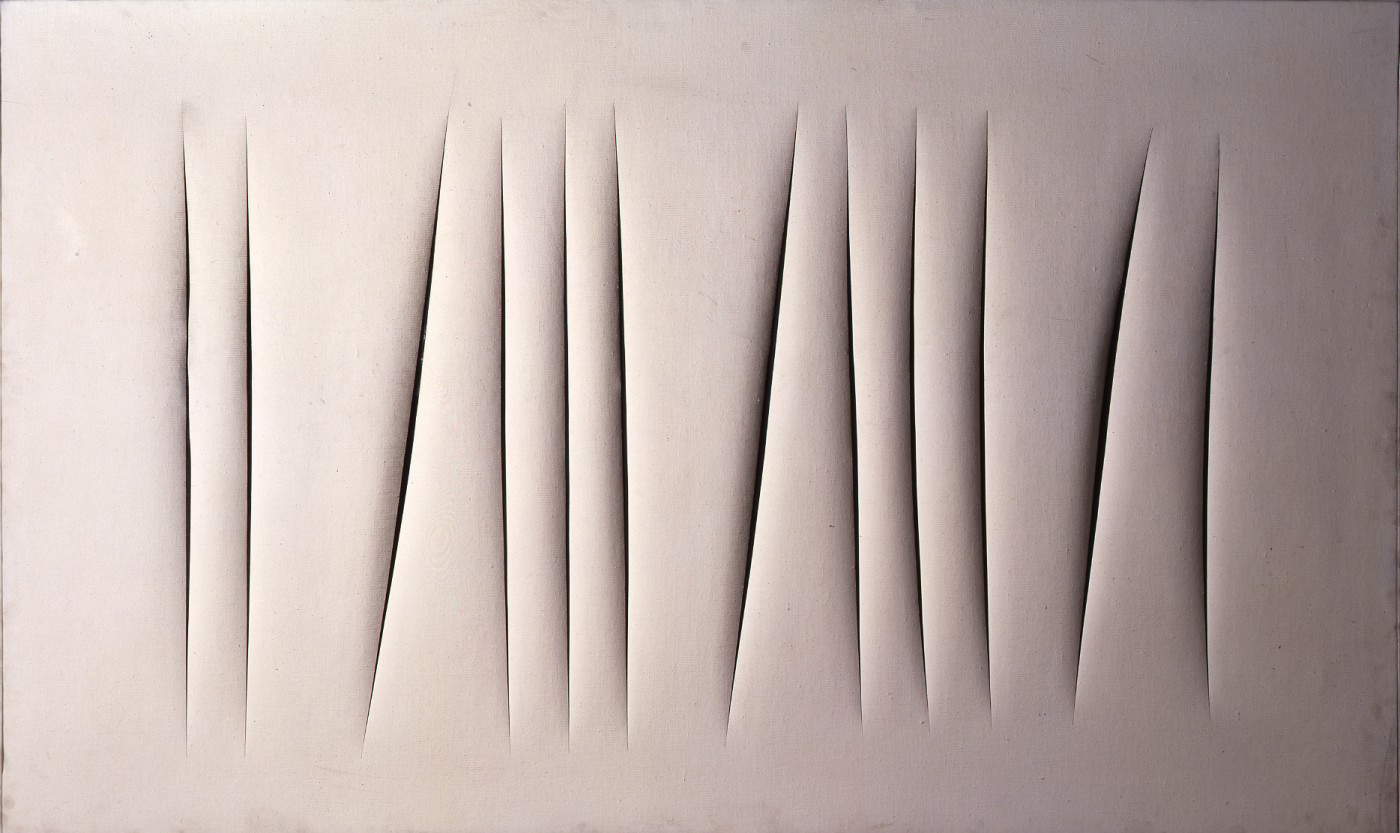

All this where there exists, however, an imagery that is capable of satisfying the populist taste or, more simply, his thirst for plots: the aesthetic populist does not, to use an image of Labranca’s, seek meaning behind the work of art, despite apparently, when faced with a work that is difficult or impossible for him to decode, he wonders what its meaning might be. The aesthetic populist, on the contrary, seeks a plot, and for that reason a work by Fontana or Burri will be incomprehensible to him: and since every hermeneutic attempt appears to the aesthetic populist as anintellectual activity, the most tangible consequence of Jameson’s assumption about the negative symptom of populism will be hatred, contempt or boorish sarcasm toward all those art forms that do not convey a plot, but require interpretation in order for a meaning to be grasped or at least a message to be derived.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1964; cementite on canvas, 190.3 x 115.5 cm; Turin, GAM) |

The effects of aesthetic populism on cultural production (without going into the merits of artistic production) can be easily seen by scrolling through, for example, a list of the most visited exhibitions by the public. For the most part, these are exhibitions specially packaged to pander to the prevailing taste (according to which, moreover, art must necessarily coincide with beauty, an assumption underlying the nefarious, and populist, rhetoric of beauty that corrupts many discussions on cultural heritage), exhibitions that do not set out to achieve scientific objectives, and which are often not even supported by an adequate research project, even if animated by merely popularizing purposes. And these are in several cases exhibitions that caress the populist purpose according to which art does not need interpretations, let alone interpretations provided by scholars (whom the populist vulgate often points to as guilty of wanting to exclude so-called ordinary people from the enjoyment of art), but it would only be a matter of emotions, and to have a satisfactory experience it would be enough to be guided only by one’s own feeling towards the work (and often, if empathy does not run between the populist and the work, it happens that the very qualities of the work are questioned). An intention that meets with wide favor by virtue of the fact that even art has been affected by the main assumption of populism in politics (“one is worth one”), and consequently the majority is also right when it comes to determining what is art and what is not, or at least in what way it should be accessed. Therefore, aesthetic populism, in essence, has made art a kind of entertainment, a divertissement for its own sake: if the majority is always right, Pedullà points out, “there is no spiritual ascent to be made (e.g., as self-education in the variety or historicity of taste),” and consequently “from here to revolt against the cultural elites the step is short: up to intolerance of any form of complexity.” Simply, vox populi, vox dei.

It therefore seems reasonable to assume that aesthetic populism today succeeds in directing the production of many exhibitions, books, television programs, and, in general, cultural products, and thus succeeds in charting what for many are the only paths to culture: a culture that is, however, deprived of its substance, sweetened and continually worn down. Aesthetic populism, however, is little talked about, and perhaps there is a need for the topic to be able to manifest a more consistent presence within the cultural debate: it is, after all, a matter of getting the message across that, in the meantime, one will never be able to definitively emerge from postmodernism unless an alternative route to aesthetic populism is presented, and that (by placing itself in front of another side of the question) art is not entertainment, and the approach to art (and to culture as a whole) cannot ignore its complexity.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.