Today the public needs clarity more than ever, and the purely inclusive museum must be a benchmark of the real thing. Often shy schoolchildren ask me under the cackles of their classmates whether what they see is original or not. I answer them that that is the fundamental question and that the only reason for their visit to the museum lies in the miracle of discovering the original works. However, if the aura of the original artwork is to be continually reaffirmed, whose fault is it if doubt exists and there is a hope of silencing suspicion? Beyond the divergent views on lending authentic works to commercial events, the real subject is that of the materiality and cultural context of the object.

Some cultural workers are now applying the syrup principle to the artwork. A single dose of Van Gogh or Klimt diluted into five doses of projection on the walls and a dose of Wagner creates an immersive experience far more enjoyable than the contemplation of a painting possibly abraded, small (“I never thought it would be so small” is the most frequent comment of the disappointed visitor in our museums) and impossible to illuminate perfectly because of reflections on the paint and protective glass.

Is there a chance to win this already lost battle? I will recall a personal experience : I had taken my daughter, who was then about ten years old, to see a soccer game at the stadium. A few minutes after the whistle blew, she asked me why there were no replays like on TV. But then he enjoyed finding meaning in making out the distant shadows of the players from the corner, listening to spontaneous pundits like his father and other spectators, eating a sandwich and drinking an American soda, and then returning home on a crowded bus.

Seeing the original work of art is an effort, not in the sense of a snooty elitism that no longer has its place in museums but in the idea that one has to get to the place where the discovery takes place: the armchair in the living room will never be the place of art revelation. Mind you, the museum is only a conduit like the theater or the concert hall. In a world that would not have known conquest, destruction and theft, the works would still be in the palaces or churches for which they were designed with precise calculations of perspective and lighting. The museum is like democracy according to Churchill, the worst form of transmission of works, except for all those other forms tried so far.

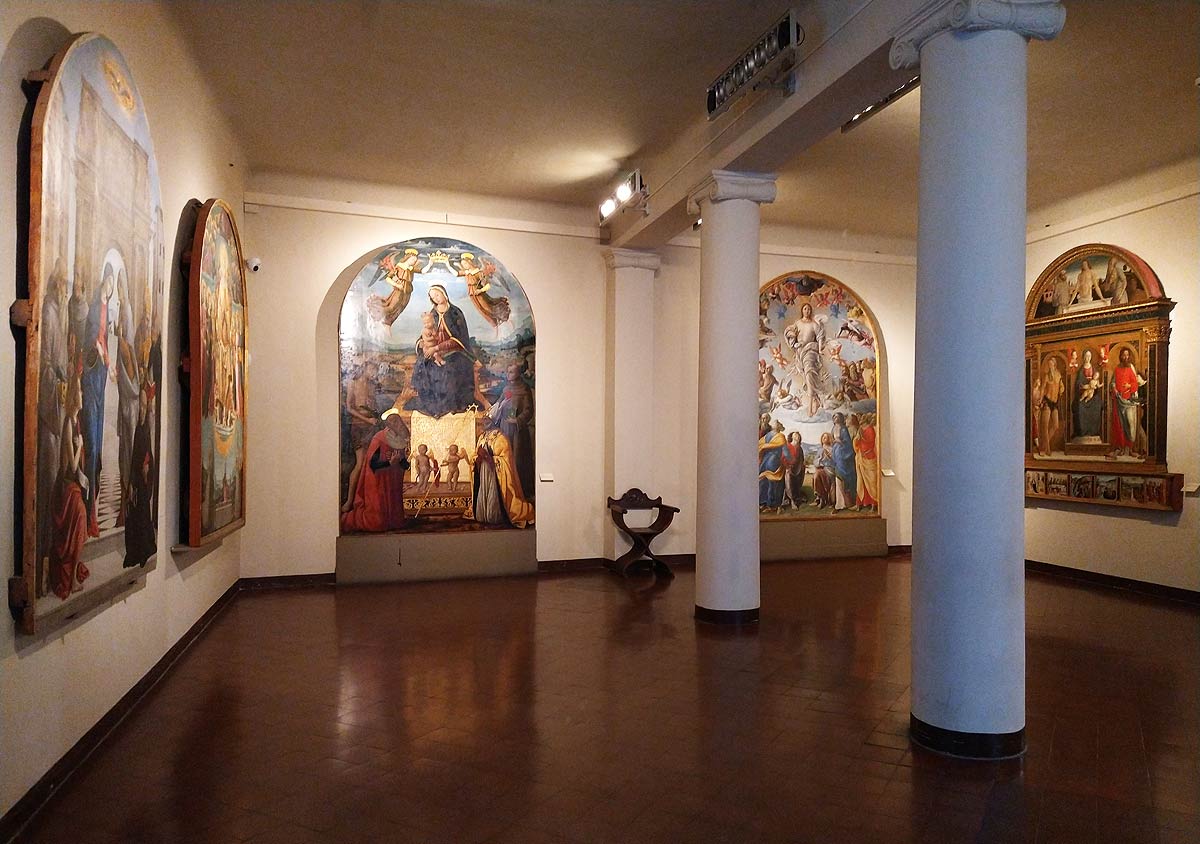

Reproduction even the most faithful never makes sense on its own even to replace a non-lendable work, indeed its very perfection increases the risk of manipulation of the viewer. Instead it must be included in the reconstruction of stumped ensembles such as modern additions in restorations, highlighted, never entirely superimposed on the ancient parts. It must then be explained and justified to avoid any misunderstanding. In the context of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena we are interested in evoking the missing parts of the polyptychs, the missing woodwork, the history of earlier restorations.

The nobility of the museum lies in offering a catalog of the lost, an inventory of the possible, and an honest deployment of the reflection of what were the beauties of the past, all set against our contemporary minds and sensibilities. And there is no indication that in the future audiences will stop lining up to see live this spectacle ennobled by the care of the women and men who have handed it down to us to this day.

This contribution was originally published in No. 18 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.