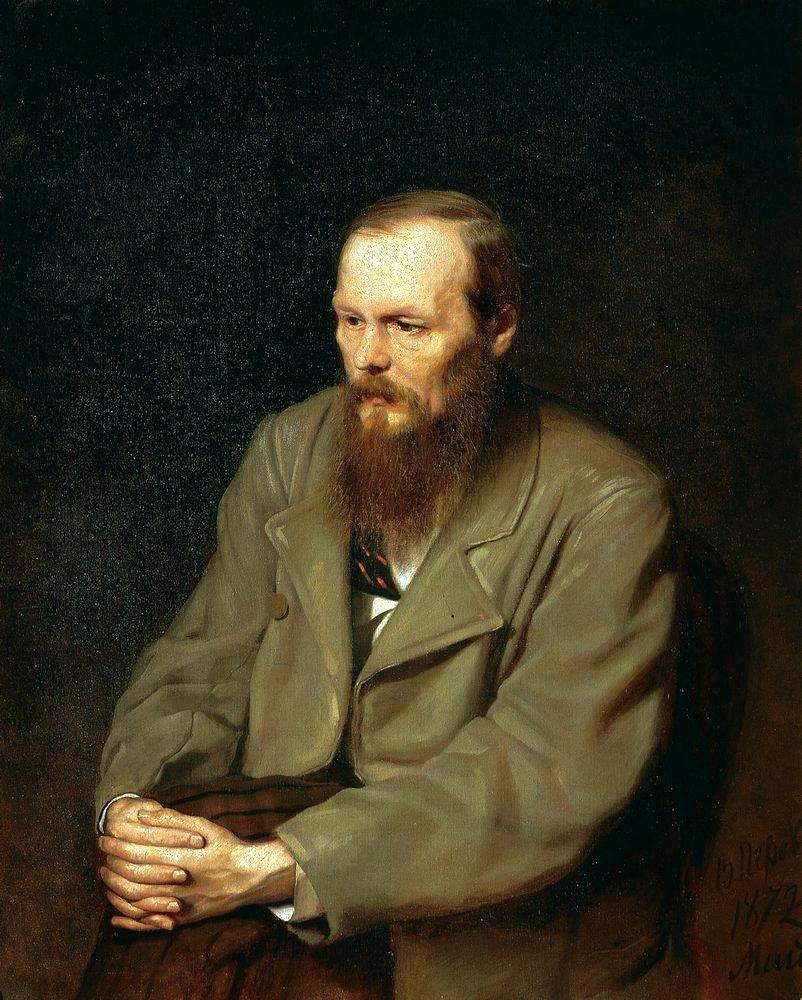

It is this morning’s news that the University of Milano-Bicocca has been caught up in the temptation not to have people talk about Russian culture: the writer Paolo Nori, a great expert on Russian literature, on his Instagram page, in a broken voice, denounced the attempt by the Milanese university, which sent him an email to inform him of the postponement of a course on Fyodor Dostoevsky. “The purpose,” the missive reads, “is to avoid any form of controversy especially internal controversy as it is a time of high tension.”

Now, to those who get caught up in the urge to cancel courses on Fyodor Dostoevsky because he is Russian and because talking about Russian culture might fuel controversy, another letter should be offered, the one the great writer sent to his brother on Dec. 22, 1849 from the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he was imprisoned for subversive activity, with a death sentence commuted to indefinite hard labor. A brief excerpt: “Life is life everywhere, life in ourselves, not in what is outside of us. There will be someone close to me, and to be a man among people and to remain a man forever, not to be sad or to give in because of whatever misfortune may befall me, this is life; this is the mission of life. I understood this. This idea has entered my flesh and blood. Yes, it did! The head that created, lived with the highest life of art, that understood and became accustomed to the highest needs of the spirit, that head has already been severed from my shoulders. She is left with the memory and images created by me, but no longer embodied in me. They will tear me apart, it is true! But there remains in me my heart and the same flesh and blood, which can also love, suffer and desire, to remember, and that, after all, is life. On voit le soleil!”

One cannot fail to note the sum total hypocrisy of those who believe that talking about Russian culture can foment controversy, and then perhaps think it is consistent to sympathize with Russian citizens who take to the streets in their thousands to demonstrate, and are arrested for reasons not unlike those that led to Dostoevsky’s arrest. Besides, from whom could controversy against Dostoevsky ever come? From the warmongers who have failed to understand that censorship should be a legacy of a past we wish would not return and that pointing to an entire people as enemies or deeming them similar to the autocrat who rules them is a dangerous anachronism? By whom has it not been understood, despite rivers of rhetoric that these days we almost come to regret, that culture is one of the best tools for creating a climate of confrontation, dialogue and détente? Democracy should also exist to allow people to talk about other cultures, regardless of what happens in everyday life. Especially since, in this case, we are talking about a writer, Paolo Nori, who immediately took a stand against what is happening in Ukraine. And all the more so when it comes to grotesque results: think of the case of photographer Alexander Gronsky, who was removed from the Fotografia Europea Festival in Reggio Emilia, and arrested last February 27 in St. Petersburg (then fortunately released shortly after) because he was protesting against the war.

In situations like these, if anything, the exact opposite is needed, as Paolo Nori rightly pointed out. Already, as he himself pointed out, it is ridiculous to lash out at living Russians, let alone dead ones, who moreover if they were alive today would be siding with those protesting against the war. It would serve to read more Russian books, see more Russian art, listen to more Russian music. More Dostoevsky and less obtuse bellicose rhetoric. It serves to understand each other, not to raise barriers. We need to broaden opportunities for the exercise of critical thinking: it is dangerous to repress them, it is blind to censor them, and it is deeply undemocratic.

In 1928, in a growing climate of censorship against Russian culture that would later lead to an almost total ban on Russian literary and theatrical productions when, seven years later, some fifty League of Nations countries imposed economic sanctions on Fascist Italy for its aggression against Ethiopia, in the journal Il convegno a great writer and journalist like Guido Piovene noting the obtuseness of those who said that “one should not read the Russians because they harm us Westerners,” and equally noting the interest that many young people were developing in Russian literature, could write that “it is ridiculous to bolt the gates of an empty city, it is ridiculous seclusion that does not serve to defend wealth, but only to prevent wealth from entering from outside.” Fortunately we are no longer in the 1930s, fortunately there is no longer fascism, fortunately already this morning there was a unanimous chorus of protests against the censorship of Dostoevsky (so the controversies did rise, but they were opposite to what the university imagined) and the University of Milano-Bicocca backed down. And the situation in Italy then is quite incomparable to the situation today. But precisely because we live in a democracy today, we should emphasize and keep Piovene’s words in mind, and prevent dangerous temptations from reappearing.

Of course: the danger now seems rather far away, first because civil society is proving responsible, and second because, for now, we are still at the tragicomic stage. That is, to the attempted censorship because of the fear that someone might resent that Dostoevsky is being talked about in a university. To complete the picture we are just missing someone who proposes to replace Dostoevsky with Euripides’Iphigenia in Tauride, since it is about a guy who goes to the land now called Crimea to steal a statue: perhaps there are those who might interpret it as an act of resistance against Russia.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.