Museums, it is not enough to talk about enhancement. What should a museum be?

Following the confirmation of the appointments by Cultural Heritage Minister Dario Franceschini of the directors of three of the country’s most important collections (i.e., the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, the Galleria Nazionale d’Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, and the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, autonomous museums that have strongly centralized most of the private and public revenues in the past years) along with the publication of the Top 30 Italian museums that hosted as many as 55 million visitors in 2019, one cannot help but reflect and try to shed some light on the rhetoric of the enhancement and educational role of museums.

|

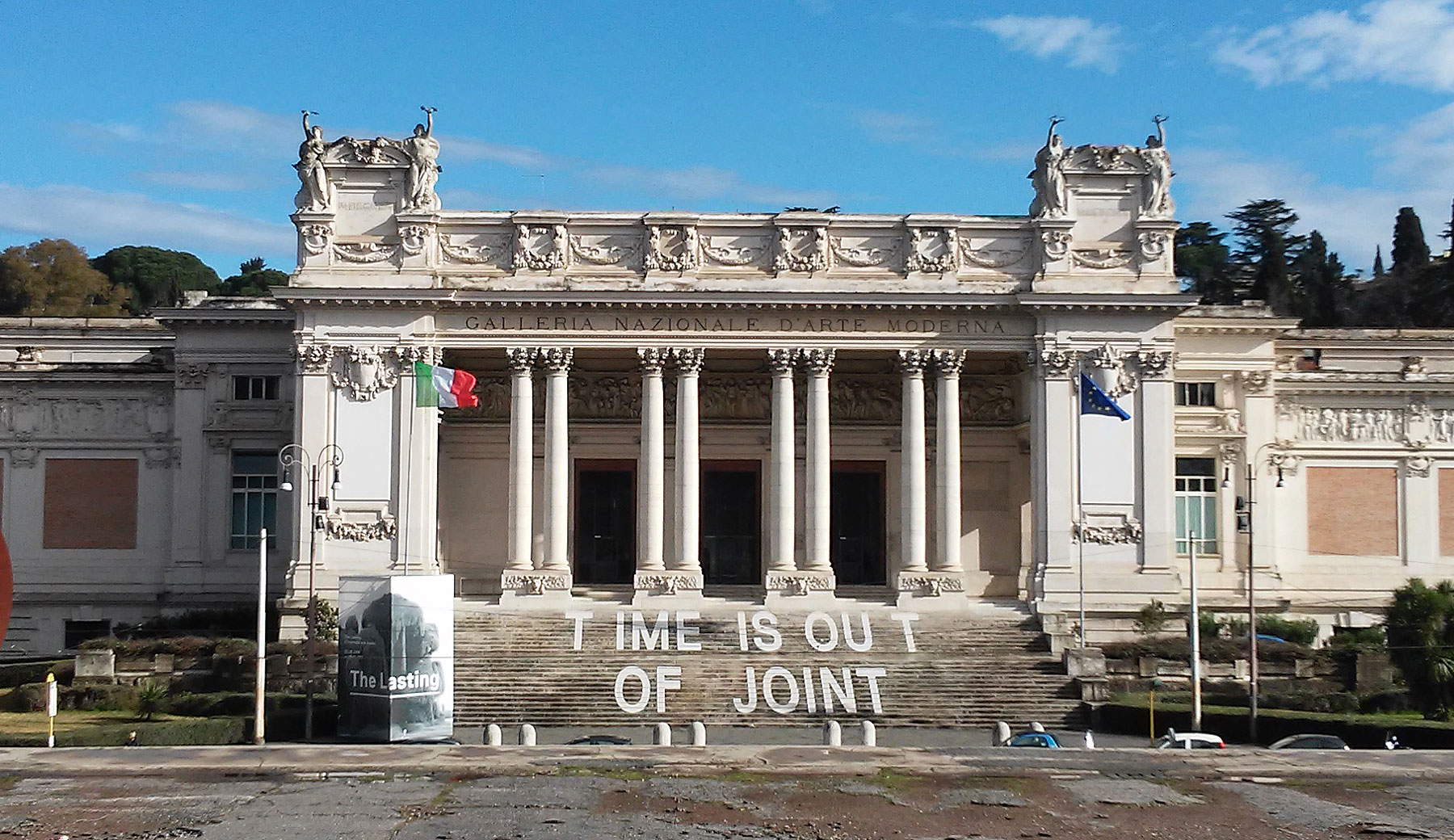

| Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

One of the trends of contemporary times, which museum policies should in no way pander to, is to promote a vision of the public as a more or less homogeneous and passive set of people who fill empty spaces without really developing their own critical sense and deeper vision about what they have seen. What happens today is that the various professionals involved in the culture sector become almost irrevocably the bearers of an abstract managerial practice often accompanied by profit-centered thinking about culture. It is clear how the critical aspects of this approach stem not from the “business” model itself (from which it would be virtually impossible to separate entirely today given the almost total absence of public funding and investment), but from its goals and policies, which change totally the moment management becomes focused on marketing as an end in itself. Simply because the thinking about the visitor changes. When we talk about “putting people at the center,” however, to what extent do we risk approaching them in large numbers but in a superficial way?How is this a reason for “development” for the area? How is it measured?

Salvatore Settis(Italia S.p.A, Little Einaudi Library 2007) traces a starting point in the very birth of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage in 1974. Already from the beginning it was made a handmaiden of other ministries (such as the Ministry of Labor) and then in 1998 (with Veltroni) changed the name by adding “cultural activities” and beginning the opening to companies for museum services; later, in 1999, competencies on sports and entertainment were incorporated. Then, with the Urbani-Tremonti-Berlusconi trio, the sell-off of heritage underwent extreme acceleration, through divestment of service management and concession of the assets themselves. Today, neoliberal policies continue with the current minister, including the critical Art Bonus (2014) and the devaluation of the superintendencies, which led among other things to the invention of the status of “autonomous museum” (Law 83/2014), all under the long shadow of the painful absence of broad-based funding for schools, culture and research (among which we recall the one billion cut to the ministry’s budget in 2008). This disquieting devaluation of cultural reality and knowledge, of all that, in short, is intangible knowledge and human need, on the one hand has caused neglect and degradation, and on the other finds a deceptive escape route in becoming a consumer object emptied of content.

If new models are to be established for the museum in contemporary times, therefore, it is not enough to talk about innovation, nor is it enough to appeal to its “educational role.” Rather, we need the museum to become a political institution, to deeply criticize its own content and to recognize itself as a common good (as history and science are). Indeed, we need to reflect on the word “enhance” and understand what it means when we talk about cultural heritage, tangible and intangible. First, it does not mean “giving” value, but rather recognizing it, recovering it: precisely because it has perhaps been somewhat lost. Second, what is to be valued? Certainly not (only) the wrapping of the art object, making museums into eye-catching stage sets. In fact, it was precisely this superficial strategy that caused the works of art to lose that “value,” and that today puts us at risk of falling into a vicious cycle, in which even if the public is stimulated in the short term, it is then lost completely in the long term. It is quite another thing that makes the public active and interested in their heritage. And this undoubtedly comes from a long, silent, but rich relationship that cultural institutions (schools first) must begin to establish with people.

So what is there to enhance? First of all, even taking the risk of being a bit abstract, knowledge. One must recognize knowledge as a human need, that “common” space spoken of by anthropologist François Jullien that generates hope for an open confrontation between different cultural subjectivities, for “if the universal depends on logic and the uniform belongs to the realm of economics, the common, on the other hand, has a political dimension: the common is what is shared”(L’identita culturale non esiste, Turin, Einaudi, 2018, p. 9).

Second, the transmission of this knowledge, which must take place not only between collection and visitor,matra heritage and community. How to do this? It is obvious that there is no one museum protocol or standard that is valid for all realities (many museologists and heritage scholars are critical of the concept of standards, from Giovanni Pinna to Salvatore Settis). If one’s only goal is to bring “together” the public and the work, one will create, on the one hand, the usual separation between “high” and “low” culture, which inevitably leads to exclusivity (and thus exclusion), and on the other hand, a surface culture that flattens everything. There is a need for museums and cultural policies in general to broaden their visual spectrum and scope. They need to (back to the point) regain a social function and a political function.

The mission of the art museum, long deprived of economic support, has perhaps lost the concept of the pedagogical, cultural and humanizing quality of visits. One does not just come into contact with artifacts but with their history and their nature of proposing a thought, a more or less creative reaction to what we experience every day. The museum must deal with telling the story of works and collections by promoting quality research (on which there has never been a long-term investment in Italy) and through the promotion of debate. And that is why, as an institution, the museum must guarantee scientific certainty about the heritage it preserves and begin to discuss it after making available all possible forms of knowledge about its collection. So many stories, all united by a uniquely human creative language. Here then disappears the paradox that museums should not make themselves the bearers of a “cultural identity,” but embody for all intents and purposes that possibility of transformation and hybridization as a political act. Political in that it proposes a coexistence that is a living together among different people.

When we too often speak of “cultural identity” either among homegrown museologists or as a precept to identify a cultural or landscape asset (Cultural Heritage Code Legislative Decree 42/2004) as a set of “cultural values,” either signifying a reactionary relationship of identification and belonging to a localist culture, we do not give proper value to the territory. Territory has always been, and will always be, the space of coexistence among different people, of the capacity for transformation, and of art as a historical, civic and human manifestation. If, however, educational purposes and investments in training (outside and inside the museum) remain in the background, or worse a burden, how can one hope to become a point of reference for cultural debate?

The art museum must politicize, not ideologize: propose more than the abstractness of a concept, the intimacy of a suggestion. Return to being a muse. An inspiring principle that tells us to glimpse the universality of the language of art, to understand how beauty and history are not aesthetic canons but human needs and quests. If we do not recognize this form of universalism, we will not be able to begin any pedagogical discourse, let alone speak of the emancipatory power of culture, because we will end up accepting a “pluralism” that does not see the invisible, that does not see images but different “figures” to be catalogued. Instead, what the museum must become, as museologist Peter Vergo suggested, will have more to do with a symphony, in which the various languages, codes (words, colors, sounds and texts) and moments (contemplation, study) alternate and leave space for each other. The museum should be the space where research is initiated, where diversity is discovered not only between cultures but between individuals, and where it is understood that creativity through the visual arts is only one of the possibilities and is transformative capacity. The social implications are enormous. Giving content to images. This is the goal that new cultural policies must strive to pursue.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.