Museum visiting is not a habit for Italians. What are museums doing wrong?

According to Istat (2021), visiting a museum does not represent a habit for Italians, relegating our country to the bottom of the ranking of EU countries in terms of citizens’ cultural participation.

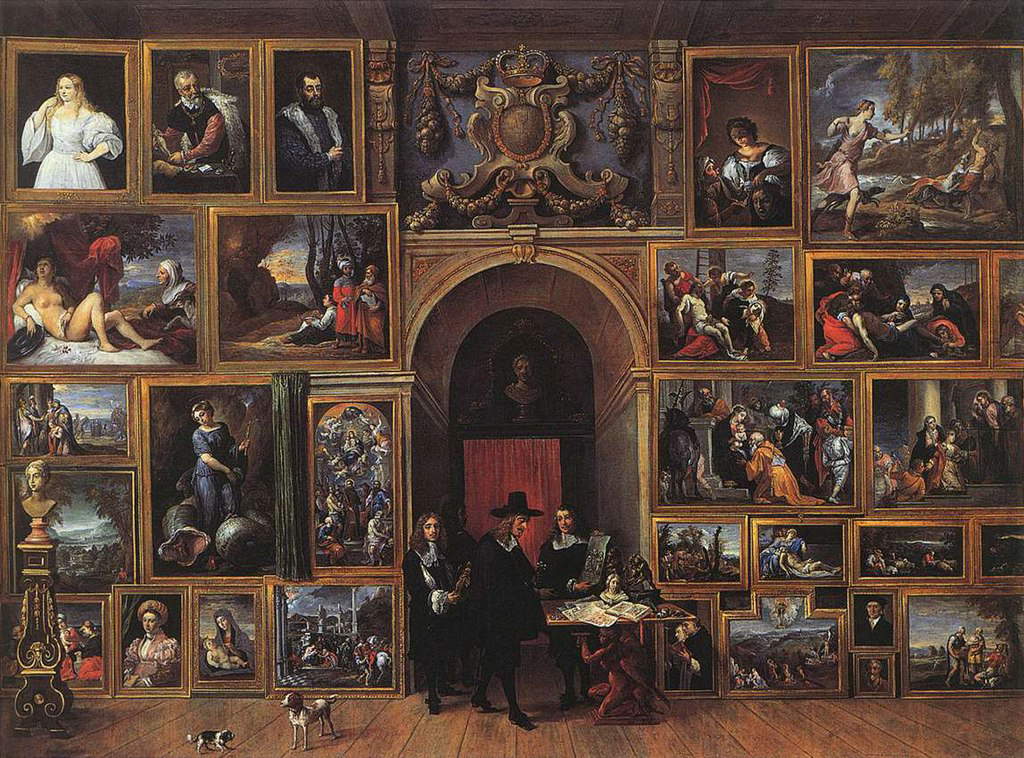

The main error found in a large part of our museums, starting with those of the traditional type of ancient art and archaeology, can be seen in the persistence of a positional cultural offer constrained by a Fordist approach. In many cases, cultural institutions continue to target selected clusters with specific skills, “sensibilities,” and “taste,” believing that, unlike in any other sphere, they must fordistically seek out audiences that fit the offer, which is considered to be of a unique, unmodifiable, and self-referential species. At the same time, many visitor surveys attest that cultural consumption still mostly responds to a demand for status symbols, driven by motivations of social prestige and aimed mainly at a few big famous museums. At the same time, the very concept of cultural heritage is often unduly linked to exemplars of particular rarity and aesthetic value, rather than referring to any tangible and intangible historical evidence having civilizational value, that is, relating to the way of life of a community lived in a given time and place.

Thus organizations dedicated to ensuring “knowledge” and “the best conditions of use and enjoyment” (Legislative Decree 42/04, Art. 6) of cultural heritage often, as well summarized by Bruno Toscano (2000), propose “a prosopopoeic, monumental and selective representation of things of artistic and historical interest” and use metaphorical and specialized language obscure to most, “far from any pragmatic meaning, from any interest in the technical reading of the spatial and temporal relations referred to by art objects as by the whole landscape.” Even the daily press (Chiaberge, 2007) has long reported that the works are often “accompanied by epigraphs drafted in ’Arctic history.’ Thus the dismayed visitor stumbles upon ampullary phenomena like ”realistic spatiality of strong perspective illusionism“ [...]. As for archaeologists [...] we go from Fibula to fistula, from rhyton to patera, from bothros to favissa [...]. Before language, the heads of bureaucrats and professors should be changed, who in writing do not think of ordinary people.”

Public organizations in charge of the valorization of cultural heritage that remain anchored to positional strategies, rather than producing an offer in tune with the above-mentioned mass democracy, characterized by social reforms including the right of citizenship to culture (Articles 3 and 9 of the Italian Constitution), contradict their own meritorious nature and, therefore, progressively lose consonance with the social and political-institutional fabric, endangering their own survival, as well as that of the stock on which they act.

The need to rethink the role, function and form of museums and the urgency of effective changes to bring them closer to citizens and foster cultural participation has been widely advocated for years at the international and national levels. Consider, for example, the Faro Convention (2005), the recognition of the museum as an essential public service (Decree Law 146/2015), as well as the new definition of a museum (ICOM 2022) as an institution “at the service of society” that operates and communicates “ethically and professionally and with the participation of communities, offering diversified experiences for education, pleasure, reflection and knowledge sharing.”

To this end, of paramount importance is the innovation of product policies and, in particular, of the core service (related to the enhancement of heritage) that is embodied in the communication of the historical information hidden in it, first and foremost rethinking its content and mode of delivery. In practice, this would involve ensuring broad and varied categories of users accessibility not only physically to heritage, which constitutes the minimum degree of supply, but above all intellectually, ensuring that everyone has as deep an understanding as possible of the wide range of meanings implicit in the assets. In this sense, the contents should be such as to reconstruct and explicate in the round the historical facts of which the goods are an expression (and not only their formal aspects), also referring each object to its context. The same Circular Letter of the Pontifical Commission for the Cultural Heritage of the Church (2001) clarified that “the historical-artistic heritage has acquired, due to secularization, an almost exclusively aesthetic meaning,” while the value of works of art cannot be understood in an “absolute” sense, but must be “contextualized in the social, ecclesial, devotional experience,” valuing “the contextual importance of historical-artistic goods so that the artifact, in its aesthetic value is not totally detached from its pastoral function, as well as from the historical, social, environmental, devotional context of which it is a peculiar expression and testimony.”

Likewise, the language used should be adherent to the concrete evidence of the phenomena and understandable to an audience not necessarily equipped with specialized skills.

In addition to this, it would be necessary to differentiate the offer because of the different clusters of demand. In addition to the usual criteria (age, education, etc.), the geographical and cultural contexts of origin could usefully be taken into account, in order to best satisfy first and foremost the local audience by offering them a presentation of objects highly contextualized with respect to the social, civil, religious, economic, artistic, etc. history of the place.

For such and other innovations through which to rethink the role, function and form of museums, the provision of highly qualified staff with interdisciplinary skills is indispensable, an aspect on which work has been going on for years(Curricula Guidelines for Museum Professionals ICOM-ICTOP 2000; European Handbook of Museum Professions ICTOP-ICOM Italy, ICOM France and ICOM Suisse 2008; National Charter of Museum Professions ICOM Italy 2005 and succ. agg. 2015, 2016 and 2017; Foundation School of Cultural Heritage and Heritage School; Universities and other training agencies).

So, the museum, through knowing and listening to its audience, should establish the most appropriate communication strategies to explicate the information potential implicit in the collections, implementing choices that are never neutral, but should be responsive to the needs of increasingly broad and differentiated clusters. Likewise, it should not be forgotten that for the consumption of cultural goods we speak of increasing marginal utility, since a satisfactory visit to one museum can only encourage the visit of other museums.

This contribution was originally published in No. 19 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.