The museum world’s view of the fate of monuments in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests could be described as pure outrage. But even so, I would choose Julia Rindleman ’s photograph as evidence of material culture on the Black Lives Matter protests. As I see it, this image represents the inherent paradox between, on the one hand, the freedoms and achievements of a society and, on the other hand, the struggle that continues unabated. It represents it thus (and, I might add, it does so exceptionally well): the two Rindleman dancers (14-year-olds Kennedy George and Ava Holloway) are standing, dressed in a black tutu, in front of the monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee marked with graffiti and spray-paint lettering shortly before its removal. Beyond the graffiti and spray paint (a nightmare for conservatives), the monument, and like it 1,700 other Confederate monuments found across America, in addition to shaping the military hero or leader they represent, have become symbols of oppression. Indeed, Kennedy and Ava’s statement is directed at the contested legacy that is now symbolized by the Lee monument, and which has been the subject of debate from the moment the idea of erecting a Confederate monument was conceived. In his letter to General Thomas L. Rosser dated 1866, Lee shared his concerns about erecting monuments to Confederates, acknowledging that such symbols would slow the formation of the nation rather than “hasten its completion.”

|

| Julia Rindleman’s photograph |

Should Lee’s words be taken as a warning, though recognized relatively late? Then, how might the contested heritage be understood and valued beyond the emotional reactions that lead to removals and culling?

There is no straightforward answer to this question, and the six strategies suggested by Hyperallergic to address the issue of contested monuments and memorials certainly represent a valid point on possible scenarios. The strategies proposed range from doing nothing, to removing, to relocating, to recontextualizing. Museums are mentioned as possible places for preservation, but not everyone agrees. Museums certainly are more than safe places to present contested heritage and material culture.

|

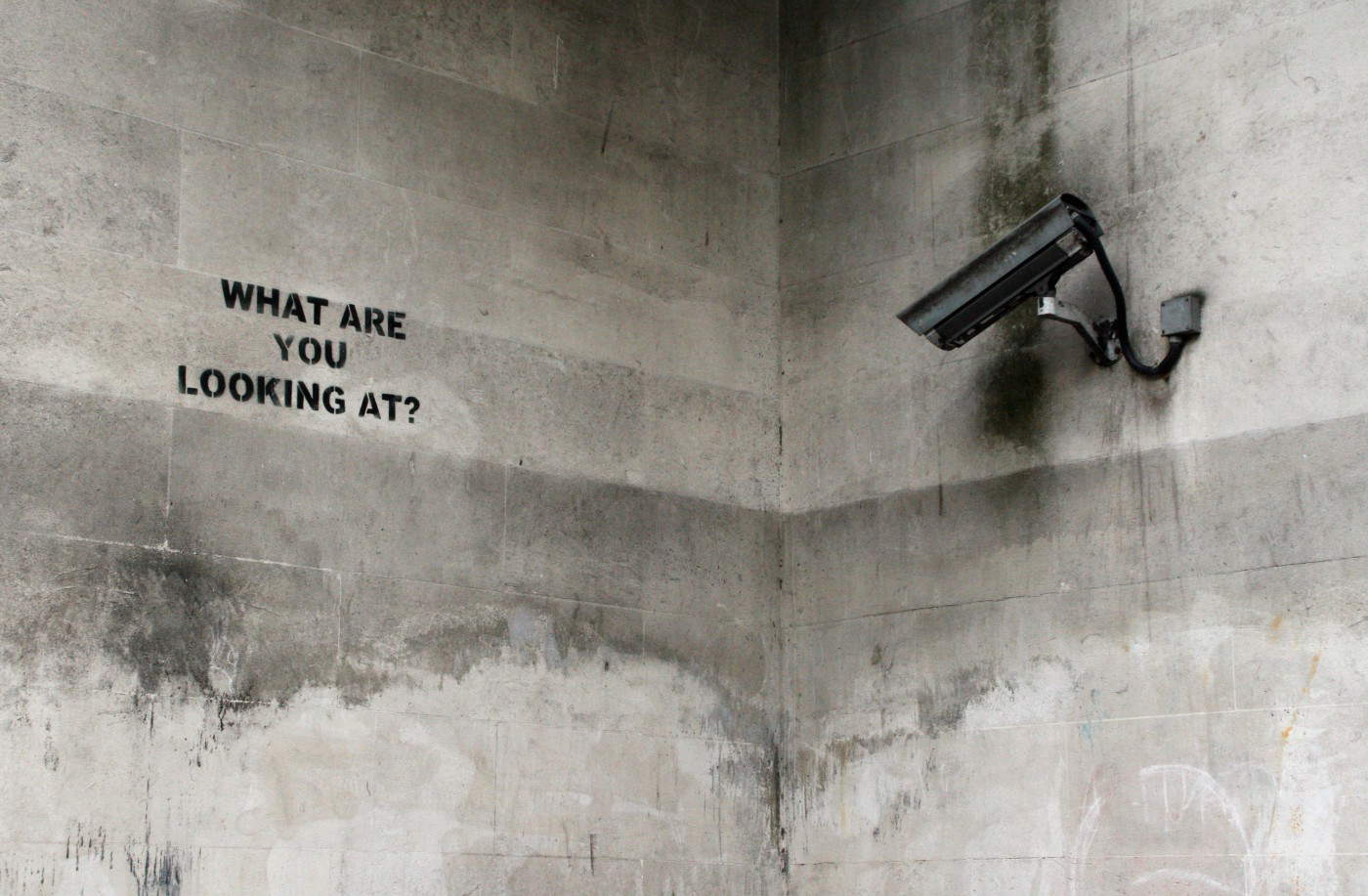

| Ph. Credit Niv Singer |

The other side of the coin

On the flip side, museums, certainly spurred on in this regard by the Black Lives Matter protests, have been active as never before in the Rapid Response Collecting strategy. The idea behind this strategy was developed by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2014 (with precedents to be traced to the History Responds project carried out by the New York Historical Society). The Victoria and Albert Museum describes Rapid Response Collecting this way on its website, "contemporary objects are acquired in response to important moments in recent history that have to do with the world of design and production. Many of the objects have become noteworthy because they have advanced what design can do, or because they reveal truths about how we live."

At the turn of the global crisis we are currently experiencing, more and more museums have begun to undertake Rapid Response Collecting actions. A recent article by Sarah Cascone on artnet.com provides very valid elucidation on Rapid Response Collecting. Aaron Bryant, curator of photography and contemporary visual culture collections at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, sees the object as a portal, a kind of medium for connecting history and the public. Peggy Monahan, director of content development at the Oakland Museum of California, also emphasizes the exceptional circumstance of being aware that we are living in a very significant moment. I agree that Rapid Response Collecting is a step forward in addressing the perceived imbalance in museum collection development practices. And as the act of protest itself becomes a producer of material culture worthy of acquisition, the democratization of the museum institution becomes more than just an ambition.

But the tendency tobias is ingrained in museum institutions far more than one might at first think. A good case study is offered by an app from the Google Arts & Culture project, the one on portraits introduced in December 2018: through this app, matches are found between one’s selfie and portraits held in museums around the world and available in Google’s database Google itself was surprised by the sudden success of the app, but the app excluded most people of color, for the simple reason that portraits of personalities of color are far from common. At the end of the day, the app worked much better for white users because the database was populated mostly with portraits of Europeans, mostly from the 18th century.

The fact is that portraits of people of color are far less common in museum collections around the world, or at least that is the case in the Western world. Taking Britain as a case study, the earliest known portrait of an African person, who incidentally is also a freed slave, was painted in 1733 by William Hoare. It does not belong to a British institution, but to the Museum of Oriental Art in Doha, Qatar.

|

| Ph. Credit Charisse Kenion |

The negative space

Both sides of the coin represent the challenges that museum institutions advocating the decolonialization of their collections face, and they are certainly not easy issues. It is a given that no matter how much effort museums may make to address the imbalances within them, the bias will remain as an inherent presence. Material culture may not be available for acquisition because it is all too well known that it can be destroyed, or at any rate it may not be attainable. Public monuments may still embody their contested narratives even if relocated to a museum. Making the decision-making process democratic about a monument that might be raised or removed could go a long way on the issue of bias. The same could be said for the material culture acquired over time by museums.

Another approach to democratizing material culture is to understand what I call the "negative space." I can explain this concept with an analogy. When a sculptor is given a block of material to sculpt, a sketch even executed quickly helps him to release the work trapped in the material. In the selective and deliberate choice of what parts to remove with the chisel, the sculptor approaches what is a very subjective opinion, which is the work when it will be completed. The act of choosing what to remove and what to keep is very similar to the way museums develop their collections. Museums form their exhibition narratives from their choices in material culture, and they continue to do this when they choose what to acquire and the modiscelects to press it. Material culture itself can also be presented and interpreted to represent what it does not represent in the immediate sense of the word and how a particular narrative has become dominant, discarding others equally relevant at the time.

This is what art historian Alice Procter is working on with her Uncomfortable Art Tours. Alice Procter’s tours are a clear attempt to decolonize museums and galleries by granting images the alternative narratives that underlie the material culture on display, beginning with the way and means by which it is represented (including through lighting and captions). These tours represent an alternative voice, an additional layer of meaning that has not been given sufficient space. And they certainly enrich the polyphony of meanings that material culture can represent and symbolize, bringing within the images those subaltern and unrecognized narratives that may have been discarded or left aside for too long. This can be an important step in the process of democratizing museums. Even if it is not an easy step.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.