A premise: The authors of this article are staunch pro-vax and ardent supporters of theextreme importance of the Covid vaccine in reducing the risks associated with the disease. However, we are less convinced of the idea of imposing a green pass or green certificate to establish heavy restrictions on the unvaccinated (unless they constantly want to undergo expensive swabs). As is well known, the government is studying the possibility of introducing a compulsory pass (issued to the vaccinated or to those who will have a negative tampon) in order to have access to various places, including places of culture (and this is the reason why we are writing this article): means of transportation, theaters, cinemas, concerts, restaurants, bars, discos. The certificate will most likely be approved by decree, thus without going through a parliamentary discussion: thus in a manner identical to that followed to manage the entire course of the pandemic.

At the moment, however, discussions are still ongoing: as we write, the regions are asking, for example, that the pass for restaurants and indoor venues not be introduced in the white zone, and instead always be required for access to discos and large events. On the other hand, the introduction of the pass to access museums seems ruled out (in France, the country from which Italy borrowed the green pass idea, the sanitaire pass will instead also be required for museums), monuments, and archaeological sites. On the other hand, it would seem safer to introduce the pass on trains, ships, long-distance buses, stadiums where the 25 percent capacity is exceeded, concerts and large events, indoor cinemas and theaters, swimming pools, gyms and discos. On the other hand, it is not known when the restrictions will come into effect, partly because so many Italians are waiting to receive their first dose of the vaccine and, from the time of booking to the call, up to a month may pass. So several solutions are open: multi-level certificate (one dose for certain activities, double dose for others), or even modulated based on regional risk, and so on.

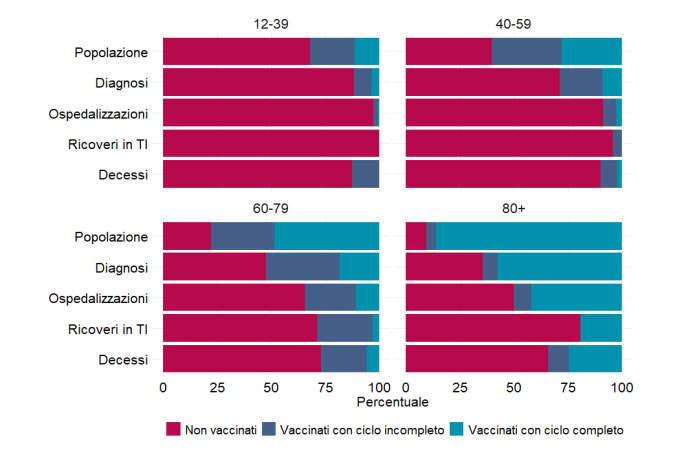

The Covid-19 vaccine is unquestionably useful in reducing the risks of hospitalization, serious consequences requiring intensive care unit hospitalization, and fatal outcomes of the disease, with naturally more appreciable results in the age groups most exposed to risk and in frail individuals, whereas, as will be seen, in young and healthy individuals the risk of serious adverse reactions resulting from vaccination is not very dissimilar to that of reporting serious consequences from infection. At present (the reference is the latest bulletin of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità published on July 14), in Italy 89.9 percent of the population over 80 years old (83.7 percent with double dose), 76 percent of the 60-79 age group (36.1 percent with double dose), 49.4 percent of the 40-59 age group (19.5 percent with double dose), and 19.6 percent of the 12-39 age group (9.2 percent with double dose) are vaccinated with at least one dose. Sars-CoV-2 diagnoses in the past 30 days affected 88.4 percent of the unvaccinated 12-39 population, 71.3 percent of the unvaccinated 40-59, 47.7 percent of the unvaccinated 60-79, and 35.7 percent of the unvaccinated over-80s. The figure for the latter group is particularly interesting, since this is the population where vaccination coverage is widest: in the last 30 days, 302 cases of Covid were diagnosed among the unvaccinated (35.7%), 58 among the single-dose vaccinated (6.8%), and 487 cases among full-cycle vaccinated (57.5%). Hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and deaths, however, are unbalanced on the unvaccinated, with 65.5%, 80.8%, and 65.9% of cases, respectively (on the other hand, 142 full-cycle vaccinees ended up in the hospital, 5 full-cycle vaccinees ended up in the ICU, and 55 full-cycle vaccinees died).

Thus, the data show that the vaccine does not prevent the circulation of the virus or even the lethal outcome, but it significantly reduces the risk. “If vaccines were not effective in reducing the risk of infection,” explains the National Institutes of Health, “no differences in the number of cases would be observed between vaccinated and unvaccinated. The observed differences demonstrate that vaccines are effective in reducing the risk of infection, hospitalization, ICU entry, and death.” The evidence suggests, in essence, that cases of infection as well as those of severe course of disease are largely borne by the unvaccinated population. That said, is it possible to quantify risk reduction? Biostatistician Maurizio Rainisio, relying on the bulletin data mentioned above, confirmed “that SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are effective in reducing severe COVID-19 cases and deaths, less so in reducing the number of infected individuals”: the vaccine, Rainisio explains, “helps reduce infections by 65-80%, but does not eliminate them. It is much more effective with regard to hospitalizations, which are reduced by about 90 percent, and even more so for intensive care and deaths, which in all age groups are reduced by more than 95 percent in the vaccinated compared to the unvaccinated.” In essence, Rainisio concludes, “the vaccine protects well against serious illness and death. It also protects against infection, but less effectively.” Further data come, for example, from England, where conclusions about vaccine efficacy are similar.

The biostatistician also notes, however, that “while vaccine efficacy is virtually independent of age, it is noted that the effect at the population level is incomparably different because of the difference in risk between age groups. In order to save one death among the very old (80+ years), it is enough to vaccinate 274 of them, while as for the young or young adults (12-39 years), it is necessary to vaccinate 167,000 (600 times as many).” The question that recurs especially among young people is: is it riskier to vaccinate or get sick? In April, the Spanish newspaper El País, cross-referencing data of hospitalized, hospitalized in intensive care and deaths in Spain by age group with adverse cases from viral vector vaccines (AstraZeneca and Janssen: Special Observatories at the time), found that, for those who contract the infection, the chance of dying from Covid-19 is always higher than the chance of developing thrombosis in all age groups ( El País’ calculation, however, does not take into account the past medical conditions of severe Covid cases). Things change as the risk scenario varies: for example, in a scenario in which out of 100,000 people 2,000 contract the disease, the risk of thrombosis is higher than the risk of death from Covid up to age 39, and the same is true for a medium-risk scenario (3,800 infections per 100,000 population) while it is similar (1.6 thromboses versus 2 deaths from Covid) in a high-risk scenario (10,000 cases per 100,000 population). In contrast, for the population 40 years and older, the risk of adverse reaction from vaccine to viral vector is always lower than the chance of dying from Covid in any scenario.

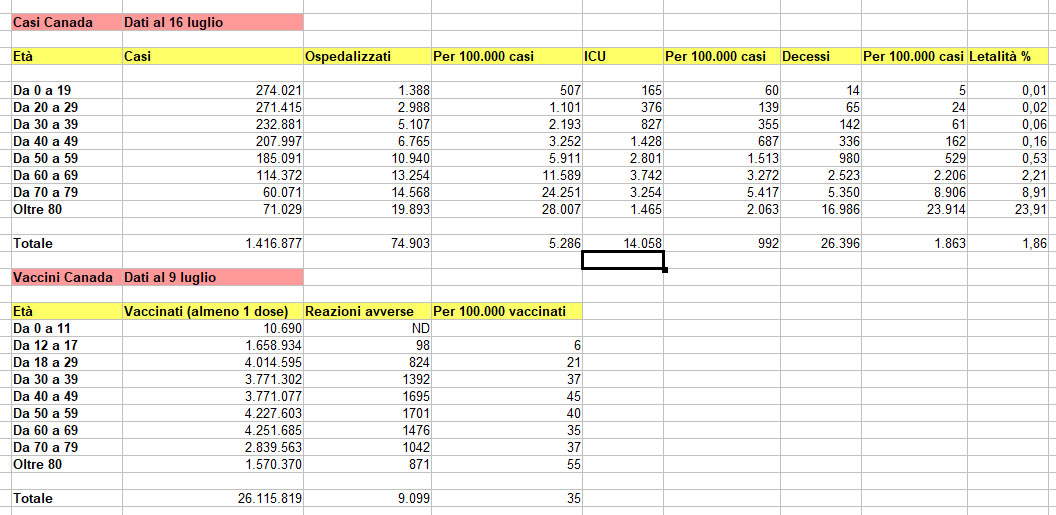

For further feedback, we crudely analyzed data from Canada (because they are the easiest to find and the easiest to cross-reference), comparing data on hospitalizations, intensive care, and deaths by age group (with reference to the July 20 Canadian government bulletin) in relation to the risk of reported adverse vaccine reactions (data can be found on the same site). It is necessary to emphasize that the Canadian report defines “adverse reaction” as any undesirable event, from the mildest (e.g., a skin reaction), to death, as well as it is necessary to point out that the numbers are very different than in Italy (in Canada so far there have been 25.1 reports per 100,000 doses, in Italy the latest AIFA bulletin speaks of 154 reports per 100,000 doses). There is no statistic by age of serious reactions, because the absolute number is given (23% of the total). Similarly, on the number of hospitalized patients, the figure on prior pathological conditions is not presented (to get a vague, but not comparable, idea, one can refer to the latest weekly report from Switzerland, where it is noted that 15% of the total hospitalized had no prior pathologies). We publish the raw data below without commenting on them, partly because it is very difficult to find complete data on the past medical conditions of hospitalized and vaccinated persons.

|

| Vaccinated in Italy as of July 14. Data from Istituto Superiore Sanità |

|

| Vaccine effects on the population as of July 14. Istituto Superiore Sanità data |

|

| Covid and the vaccine in Canada. Canadian government data, our processing |

To understand why Italy is about to enact a mandatory green pass, it is possible to refer to last week ’s statements by the extraordinary commissioner for the coronavirus emergency, General Francesco Paolo Figliuolo, according to whom the certificate could be the solution to “convince the last diehards” unwilling to vaccinate and thus reach the threshold of80 percent of the vaccinated population set as a new goal to avert widespread spread of the Delta variant. What the line is behind the idea of reaching as many vaccinated people as possible can be seen in an interview by the coordinator of the Scientific Technical Committee, Franco Locatelli, given last July 16 to Il Fatto Quotidiano: “Letting a variant like Delta, which has great contagiousness, run among young people,” Locatelli said, “means creating the conditions to cause mass uninfection. Let’s not forget that there is a substantial portion of the population that is either unvaccinated or vaccinated but not immunized because they are unresponsive to vaccines.”

It should be pointed out that the 80 percent figure refers to vaccine coverage and not toherd immunity, which is impossible to achieve because the vaccine has no immunizing effect (the ones that come closest to 100 percent immunity are the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which have a 95 percent efficacy against infection). This is what virologist Fabrizio Pregliasco was explaining back in May, speaking to the ADN Kronos news agency: according to Pregliasco, we will never achieve herd immunity: “in fact, this is the condition in which, according to mathematical models, the spread of the disease turns out to be zero, and we don’t make it, in the sense that the disease will become endemic, we will manage to lower the incidence a lot and therefore live with the virus. And this we will be able to do within 2-3 months.” According to the virologist at the University of Milan, “even if we reach 80 percent of the population vaccinated,” a target recommended as the vaccine coverage target by WHO Europe, “the disease is almost extinguished but we will never reach zero circulation of the virus.”

As of today, July 20, 58.4 percent of the population is covered with at least one dose of vaccine: we are therefore still far from the target of 80 percent but, according to some Corriere della Sera elaborations, we have reached a percentage of vaccinated people that has reduced the lethality to levels similar to those of seasonal flu. And right now, in the face of a massive increase in cases of infection, we are seeing far lower levels of hospital loads and deaths thanks to vaccines than in the past. The first doubt about the introduction of the green pass is therefore related to these data: it is not clear why such an invasive measure is used when the epidemiological situation appears to be under control. Perhaps, it would have been better to provide incentives for the vaccinated rather than restrictions for the unvaccinated: in some countries, for example, prize games, bonuses and lotteries have been introduced to incentivize those who do not want to vaccinate. In any case, if the pass is introduced, it is unclear what will happen when the 80% coverage threshold is reached: will it be abolished?

|

| European Green Pass |

There are also doubts about which places will be required to have a mandatory green pass. Places will be identified as those with the greatest risk of congregation. And again, culture is likely to be one of the most penalized areas. For now, there does not seem to be any intention to make the green pass compulsory for entering museums to go to an exhibition (although exhibitions and museums have been among the hardest hit activities, with long closures during the months of confinement despite the fact that the possibility of contracting an infection at the museum is much more remote than at other places), but the government is leaning toward at least making theaters and cinemas among the activities for which the health passport will be required.

If, however, the guide is to the risk of assemblages, there are theoretical and empirical data that suggest the low risks for virtually all cultural venues, of course within certain parameters (it is obvious that the risk goes up substantially during a crowded opening of an event in a museum). Earlier in the year, theHermann-Rietschel-Instituts of the Technische Universität Berlin had conducted a study showing that museums and theaters are the places most at risk of infection if attended at 30 percent capacity and with audiences wearing masks, all with two-hour dwell times (moreover, it is also worth noting that the study does not take vaccinations into account, since they had just begun at the time and there was very little data available). The study showed that the risk of contracting Covid is, for example, more than twice as high when shopping (with 10 square meters per person and a two-hour stay) as when going to the theater or museum, and it is equal to the risk of staying two hours without a mask in a movie theater at 40 percent capacity.

It is also interesting to note how events where basic rules (above all, spacing) were respected did not produce outbreaks: on these pages we have often cited the case of Spain, where museums and cultural venues were kept open for much of the second and third waves, we have reported the positions of cultural aldermen who have indicated how cultural venues are role models for fighting the virus, not to mention the fact that places such as cinemas and theaters have never been the source of outbreaks. Conversely, contagion can occur where distances fall, as the case of the Verknipt Festival in Utrecht, the Netherlands, demonstrates: held in early July, it required its 20,000 or so spectators to be vaccinated or swabbed in order to enter, but this did not prevent an outbreak with about 1,000 infected. Obviously, in a situation of widespread vaccination, this is an entirely manageable situation (also because it involves young people in the vast majority of cases) and should not cause concern, but it is also an indication that one of the problems with the green pass could be the sense of security psychologically induced by the patent, noted moreover also by the National Bioethics Committee. However, contagions should no longer be a problem if, thanks to vaccines, the effects of Covid become similar to those of seasonal flu: when will we get there, unless we are already there? Then there is the issue of vaccine purpose: those who vaccinate should do so solely for health purposes, whether they are selfish (I vaccinate because I don’t want to end up in the hospital and want to minimize my risk of getting sick, whatever my risk range is) or altruistic (I vaccinate because while risking little I want to help keep the infection down). With the green pass, we risk tying the choice to vaccinate to reasons that have nothing to do with the health emergency: I vaccinate because I want to go to the movies, I vaccinate because I want to go to the theater.

|

| Cinema |

The green pass also drags with it several other problems. Depending on its extent, it may become a de facto obligation to participate in social life (for those who do not want to vaccinate, it may be economically unaffordable to get a swab every other day, not to mention the inconvenience of testing). However, the de facto obligation, as Aldo Rocco Vitale notes in the newspaper L’Opinione, “is an institutionally incorrect way to induce the population to vaccinate without the appropriate legal precautions that are necessary in a rule of law in general and as provided by our Constitution in particular.” Indeed, Law 210/92 recognizes compensation for individuals irreversibly injured by mandatory vaccinations: however, since anti-Covid vaccination is not mandatory, compensation would not be awarded. One wonders, therefore, why the adoption of compulsory vaccination for the most at-risk groups has not been considered, in exchange for the recognition of compensation, rather than evaluating the introduction of a de facto obligation for all (this is probably because the vaccines are still in an experimental phase). Moreover, Vitale further notes, “the very Constitutional Court, recently, in the midst of the 2020 pandemic crisis, ruled in its 118/2020 decision that compensation for side effects must necessarily extend even to vaccines that are only recommended (as for now are the anti-Covid vaccines) provided that, in addition to the causal effect between inoculation and psycho-physical integrity damage, there is patient reliance on the basis of a public vaccination campaign (a requirement evidently present in the case of anti-Covid vaccination, especially if induced by green pass).”

Then there are practical issues. If one books up for the vaccine, one may not necessarily be able to get one’s first dose in a reasonable timeframe (taking into account the fact that almost half of the Italian population has not even inoculated itself with the first dose). Younger people are therefore at risk of having to complete the vaccination cycle in the fall: if the mandatory green pass is introduced earlier (there is already talk of August), what will those who want to vaccinate but are waiting have to do? Will a 25-year-old who is booked and will complete the cycle in October have to undergo frequent swabbing for two months if required to attend places where the pass is required (very trivially, if he has to take a train to work every day)? Logic should suggest theintroduction of free sw abs (which in any case do not save the inconvenience to those who have to undergo them) for those who have booked, running the risk that unrepentant no-vaxers will continually book and cancel until the emergency is over in order not to pay for the swabs. In the case of paid swabs, it will produce a serious and unacceptable discrimination dictated only by bureaucratic time, and which, moreover, will also affect those who intend to join the vaccination campaign. If, on the other hand, we wait until a good percentage of Italians have been vaccinated, what will be the point of the pass if the 80 percent coverage threshold is reached or nearly reached? Then, in the event of an abrupt introduction, there is the backlash that could be suffered by businesses already battered by the emergency: cinemas, theaters, bars, restaurants and so on. Those who are waiting to be vaccinated and have to take a swab to go to the movies will probably be inclined not to go.

Regarding the constitutionality of the green pass, it is useful to report the two opposing views: the one in favor by Giovanni Maria Flick and the one against by Ginevra Cerrina Feroni. Flick believes that “the current constitutional system allows vaccination to be made compulsory, based on Articles 16 and 32 of the Constitution, which respectively protect freedom of movement (thus the possibility of socialization) and health understood as a fundamental right of all citizens and as the interest of the entire community, only through a law. It is therefore legally permissible to introduce the Green Pass. There is the possibility of thinking about mandatory vaccination especially for certain professional categories who work indoors, in crowded places and in contact with the frail and minors. In my opinion, it is necessary to persuade people as much as possible to vaccinate with adequate information; otherwise, it is necessary, following a scientific technical opinion of the competent bodies, for the policy to decide whether to restrict not personal freedom but freedom of movement. It is necessary to safeguard not only the health of the individual but also of others and the community, and it is the task of policy to make socialization conditional on vaccination. Only people who for health reasons cannot vaccinate should be exempted. The freedom of the individual in these aspects must be coordinated with the principle of solidarity and its mandatory duties, as Article 2 of the Constitution recalls.” So instead Cerrina Feroni: “What will the green certificate be used for? The vagueness could open up disproportionate uses of the certificate, perhaps with differences between Region and Region, not only to attend a big event (which may be reasonable), but perhaps to go to a restaurant, to the theater or to exercise fundamental rights-duties, such as going to school or work. That is, the risk is that compulsory vaccination, even in the absence of law,becomes so surreptitiously. This is the heart of constitutionalism. Caution is needed.”

A final look, finally, at how other countries are doing. At the moment, the only country pondering the introduction of a health pass is France, from which, as mentioned, Italy copied the idea. In the other major countries, no one has made similar proposals yet. On the contrary: in Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel has ruled out the possibility of introducing coercive measures, appealing rather to the reasonableness of citizens. In the United Kingdom, “Freedom Day” was declared last July 19, the day of freedom from the restrictions in force, despite the large increase in cases (which, however, are not causing any particular problems at the moment, thanks to vaccines), and despite the fact that some museums (such as the British Museum and the National Gallery) have kept in force the distancing, the mask requirement and the reduced capacity, given the trend of infections in the country. No certificate requirement in Spain either. Among the smaller countries, a pass similar to the one being sought to be introduced in Italy has been in place in Denmark since April: it is called “Coronapas,” is issued to those who are vaccinated, those who have been cured for at least a year or those who present a swab taken within 72 hours, and is required for museums, cinemas, amusement parks, zoos, gyms, sports arenas, stadiums, hairdressers, spas, bars and indoor restaurants. In short: practically everywhere. Similar passes have also been introduced in Latvia (for indoor cinemas, shows, bars and restaurants), Austria (for restaurants, hotels and nightclubs), Portugal (only for indoor restaurants, and only in the most at-risk municipalities), Luxembourg, and Cyprus. Passes will also be launched shortly in Ireland and Greece.

Finally, it is noted that rates of vaccinated population are in no way correlated with the presence of coercion: that is, countries where passes to participate in social life are in place do not have much higher rates of vaccinated population than countries where there are no restrictions on the unvaccinated. Referring to the data diagrammed daily by Lab 24 of Il Sole 24 Ore, today, July 21, in Italy at least 61.70 percent of the population has received a dose. Here are the percentages of other countries: France, 54.42%; Germany, 59.24%; United Kingdom, 68.20%; Spain, 62.10%; Denmark, 67.38%; Latvia, 38.42%; Austria, 57.11%; Portugal, 64.70%; Cyprus, 56.40%. Other countries where there are no passes: Norway, 58.90%; Sweden, 58.34%; Finland, 64.35%; Switzerland, 52.10%; Belgium, 66.50%; Netherlands, 67.69%.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.