The Venice Biennale and the Italian Pavilion are litmus tests of a crisis in contemporary art that has been dragging on for at least ten to fifteen years. As I have motivated many times in recent years, the contemporary art system (market and events) is based on four fundamentals that do not need quality and judgment over content (public money, collecting, tax breaks, niche advertising). By “quality” we mean the ability to address the most pressing issues of our time, disentangling ourselves from the past century and thus avoiding derivative language and nostalgic poses. The citation of the past may be there, indeed perhaps it is inevitable, but it must become a bridge to deal with the present and not a way to fall back on the past. Every year the major events in contemporary art become symptoms of this crisis that the system does not have to face and solve.

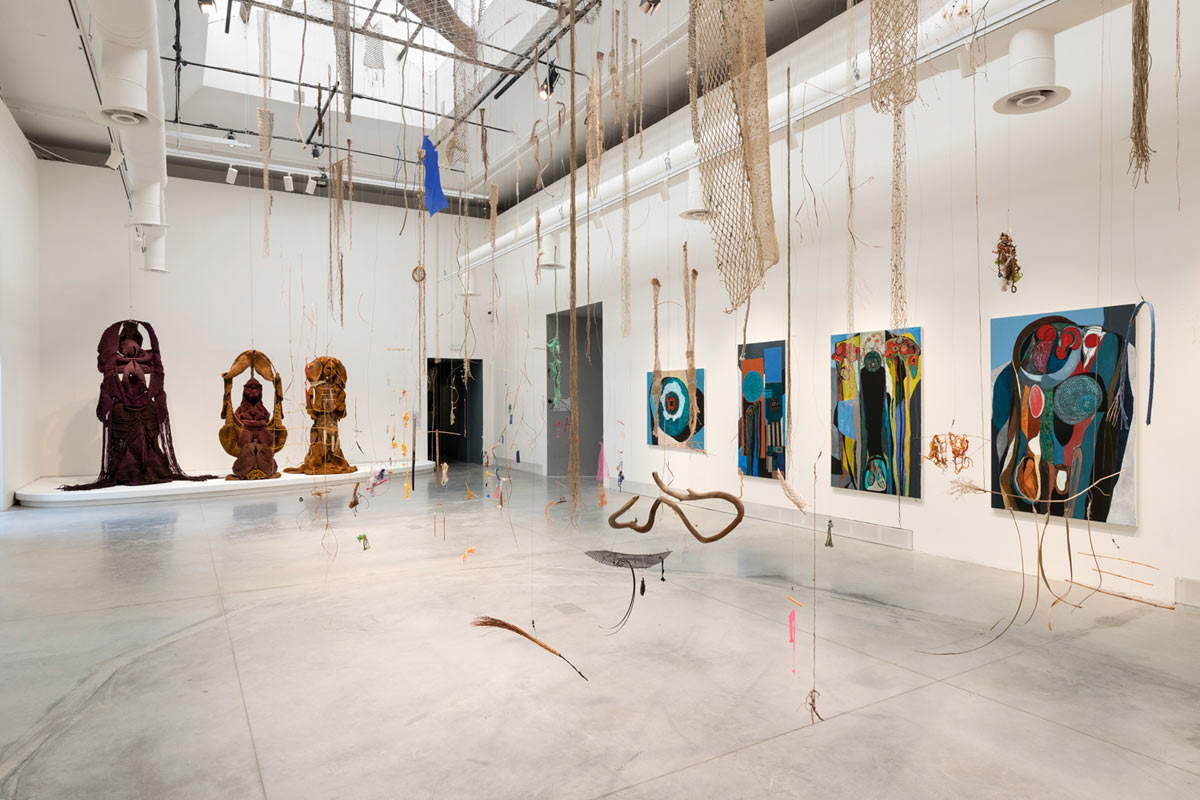

What is interesting is that the international exhibition curated by Cecilia Alemani at the Venice Biennale and Gian Maria Tosatti’s Italian Pavilion are two extremely explicit symptoms. The first step the sick person must take in order to be cured is precisely to recognize his illness through his symptoms. Cecilia Alemani’s Biennial, strongly supported by modern artists such as Paula Rego, when read through the works produced in the last ten years becomes an extremely conservative and reactionary exhibition, where the surreal element becomes a “wacky thrill” to be provided to the visitor of an “adult Luna Park.” It is evident how the artists have chosen to take refuge above the pedestal of the work in order not to have to face a present that they do not know, and more importantly, do not have to face.

To use a definition I coined in 2009, it is moving from the evolved Ikea to the “Maisons Du Monde”: the works become harmless knick-knacks, pleasant trinkets for a return colonialism. But the fault does not lie with curator Cecilia Alemani, and on this we must be very clear: the fault lies with a national and international menu that in the last two decades has not produced quality artists except in a derivative key of modern and 1990s art. No one brings these things out because there are only insiders in the audience who have to maintain good relations with everyone in order not to lose job opportunities.

A true and passionate audience does not exist, as the affair of Gian Maria Tosatti, the only artist in the 2022 Italian Pavilion, would have jolted a true and passionate audience. Tosatti until a few months ago was a marginal artist on the Italian scene, and suddenly he got three important appointments (sole artist at the Italian Pavilion, artistic director of the Quadriennale in Rome, solo project at Hangar Bicocca): a situation that in Italy, a country where we struggle to have public competitions carried out in a transparent way, is not nice to see. In his press conference a few days before the invasion of Ukraine on Putin’s orders, Tosatti called the war and the Ukrainian issue “bullshit,” because the real problem is that man must evolve (“We never move: this is the battle, the war we have lost: we are not evolving.”). But ours does not explain what this evolution consists of and tells us of a civilization in decline, when anyone who knows history knows that we do not live in “the best of all possible worlds,” but certainly “the best of all worlds that have ever existed” as levels of well-being, freedom and health. But of course the narrative of decline is very convenient for a certain rhetoric that goes so far as to quote Pier Paolo Pasolini who in 1975 would have given all of Montedison to have fireflies.

And it is precisely a failed factory during the Covid that is the protagonist of Gian Maria Tosatti’s Italian Pavilion. Too bad that without welfare, to which Montedison also contributed, perhaps that factory would never have existed and Covid would have made millions of deaths. Tosatti wants to talk to us at all costs about an “industrial failure” without realizing that his Italian Pavilion was financed by that same industrial system that he himself points to as “bankrupt” (1.4 million euros come from Valentino, haute couture, and Sanlorenzo, luxury boats) and for 600,000 euros from the state. That is, by the same citizens who must then visit, still paying, this same Italian Pavilion.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.