Leonardo da Vinci's loans to the Louvre: dialogue between Italy and France must continue, on a scientific basis

Before entering into the merits of the topic of the loans of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Italian” works to the Louvre, it must necessarily be premised that, if the masterpieces of the great Tuscan artist were to finally leave for the temporary move to Paris, it would certainly not be a matter of Italy’s subservience to France. We are certainly not discovering today the existence of international cooperative relations in the field of cultural heritage, which often result in the exchange of works moving from one country to another. Only in the last few months, just to advance a few examples, as part of a collaboration between Italy and Russia some works of the eighteenth century Veneto have left for the Pushkin Museum, and Moscow has then reciprocated by sending to Vicenza some paintings by Pushkin himself, while Italy and France have already worked together for the exhibition on Caravaggio in Paris: in return, a number of works arrived from the Jacquemart-André that made it possible to mount in Rome a small but fine exhibition on Mantegna and nineteenth-century collecting, and in Milan an unprecedented comparison of Caravaggio and Rembrandt.

|

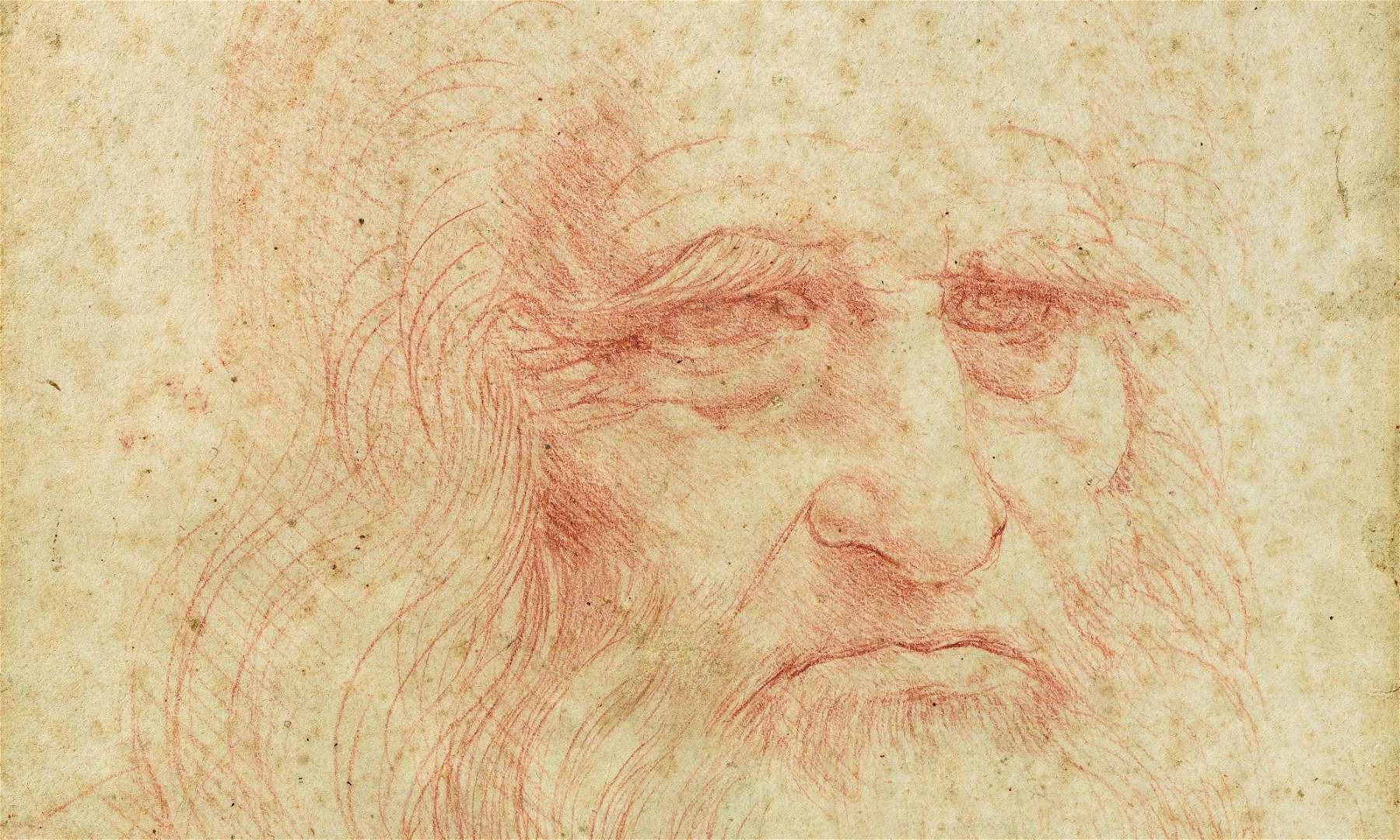

| Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of a Man Known as Self-Portrait, Detail (c. 1515; sanguine on paper, 33.5 × 21.6 cm; Turin, Biblioteca Reale) |

It is then certain that such exchanges are not always founded on scientific grounds and rather concern logics that have little connection with art: already some twenty years ago, Francis Haskell warned us that very often exhibitions are organized not for cultural reasons, but by pandering to commercial or political dynamics (risks that, one might add, increase during anniversaries, which often have the unfortunate defect of clearing the worst and most useless operations). And Haskell reiterated that the only permissible moves should be those motivated by serious reasons of scientific utility. Can this be said of the major exhibition that the Louvre plans to organize to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death? Will the works that are expected to leave Italian museums temporarily and move to Paris go to enrich an exhibition that will significantly advance knowledge about Leonardo’s work? Is the Paris exhibition the result of a valid scientific project animated by important research? Are there considerable novelties compared to the major exhibition on Leonardo held at the Royal Palace in 2015? These are the questions one would need to ask when faced with the possibility of Italian museums sending their masterpieces to France.

Yet, it is a topic that would seem to interest few or no one. The loan of Leonardo’s works to the Louvre, unfortunately, has become a political topic: on the one hand, there are those who want to reject it on nationalistic grounds, citing the pretext of Leonardo’s Italian-ness and arguing that, as a result, the main events related to the 500th anniversary should be held in our country (and, at least in the memory of the writer, such interference in international cultural exchanges had never been seen), while on the other hand there are those who would like, on the contrary, to send the works to France as a sign of détente at a time of rather troubled relations. All of these are shaky arguments: in the first case, because it is an anachronistic and illogical absurdity to refuse a loan solely on the basis of the artist’s nationality (culture and research, contrary to what many people think, know no barriers or borders), and because Italy celebrates the anniversary in a more than worthy manner, with top-notch exhibitions scattered throughout the country (from the Codex Leicester exhibition at the Uffizi to the exhibition on Leonardo’s drawings in Turin, from the palimpsest dedicated to Leonardo at the Ambrosiana in Milan with a focus on the Codex Atlanticus to the exhibition showcasing Wenceslaus Hollar’s unpublished engravings from Leonardo’s drawings). And this is without considering that Italy already had its own major Leonardo exhibition three years ago: the one, mentioned above, at the Palazzo Reale in 2015. In the second case, because it would equally be an instrumental use of the works of genius.

Therefore, the position of the minister of cultural heritage, Alberto Bonisoli, that the loans for the Louvre have nothing to do with the current tensions between Italy and France seems sensible: on the contrary, the minister has correctly offered availability for a dialogue. Here: it could be added that dialogue should avoid that evaluations are based on those instrumentalizations mentioned above, and on the contrary be motivated by scientific reasons. There are works declared immovable by their museums, and this is certainly not to spite the French: for example, theAnnunciation and theAdoration of the Magi of the Uffizi are included in a list of works, drawn up by former director Antonio Natali in 2008, that cannot leave the museum, either for conservation reasons or because they are iconic masterpieces of the museum, the ones that every visitor expects to find walking through its halls. Right, then, that the current director Eike Schmidt has seen fit to stick to the usual principles by denying the loan of his museum’s masterpieces to the Louvre (which, likewise, has masterpieces that it does not loan, for the same reasons). So there is no point in insisting on a move: the final word should rest with the entity whose responsibility it is to protect the work. However, there are also many works that can leave without any problems, and if curators and the exhibition’s scientific committee believe that their presence is important for the exhibition, and at the same time they manage to find acceptance from the lender, we do not see any valid reasons to support a possible denial.

On the other hand, there is also to consider that loans to the Louvre would not be one-way: France, of course, will reciprocate. Therefore, the councilor for culture of the City of Milan, Filippo Del Corno, is right when he stresses that a solid collaboration between Italy and France should be guaranteed for the Paris exhibition on Leonardo da Vinci, also because of the historical, social, cultural and economic reasons that bind the two countries, and that our cultural policies should be consistent with those of a great European country. And this should result in a peaceful collaboration that is profitable for both countries, but at the same time is able to avoid forcing. In other words, it is necessary and proper that Italy and France continue to dialogue on the basis of the scientific and cultural constraints that operations of this kind should underlie: as has always been done and as should continue to be done on this occasion.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.