The following statements are an intentional contradiction, of which I am fully aware. There is much truth in contradictions, I dare say. But how can something, especially an institution, be a contradiction of itself and of its own raison d’être? How can a museum be something it is not, and how can all this distinguish the future world of museums? This intentional contradiction has as its backdrop the whole discussion that has been going on for some time, with controversy, resignations, and a deep crisis at ICOM (International Committee for Museums) over the definition of museums. I always remain of the opinion that the museum of the twenty-first century is an undefinable institution, and this is paradoxically due to the fact that the varieties and mutations of the idea of the museum have enriched so much the world of museums where innovation always comes from the peripheries. The label of “nonentity,” in fact, has little to do with the standard definition of the museum. It should be recognized in this sense that the public’s perception when imagining a museum and what a museum represents is often something very different from any universal definition of “museum.”

The idea of “nonentity” is itself a matter of relevance-or, rather, irrelevance! We can say that something is a “nonentity” when, regardless of whether it is an institution, a person, or an art museum, that something becomes irrelevant to the present moment. Irrelevance works in two ways. In the first case, it may be that the context has evolved in such a way that the institution has become divorced from the circumstances of the present and has fallen behind. In the second case, it may be that the museum has evolved so much more than its context that it is perceived as an alien, exclusive, and detached entity--thus irrelevant. There are striking parallels with the avant-garde movements in art history, which were often controversially received at first, and were later accepted and recognized enough to become landmarks.

The context or local cultural landscape also plays a decisive role in the community’s understanding and recognition of the museum institution. In conservative suburbs, non-museums may need years, if not decades, to become <em>mainstream</em>. They may not even find fertile ground to grow, despite the fact that the museum landscape is more interconnected than ever. And yet, even if non-museums were to succeed in flourishing, the more conservative or those on the peripheries might slow the process from initial controversy to becoming a landmark. The risk would be to weaken and wither exciting projects.

|

But then what is a non-museum?

We can define a non-museum as a museum institution relatively lacking in relevance and significance in the present moment because it rejects the stereotypical standards and norms of what constitutes a museum institution. And it would fail to qualify as a mainstream museum on many counts for the simple reason that it would often fall outside a standard definition. I can give the example of two museums among many well-known and especially lesser-known ones, including those that would have no hope of surviving for long.

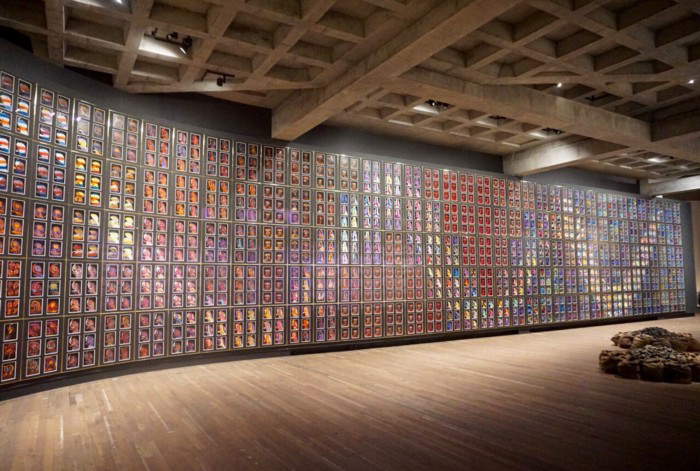

MONA, the Museum of Old and Modern Art in Tasmania, has been called a "subversive adult Disneyland" because it challenges our perception of what art should be and what we recognize as art. The museum’s website reveals much about the vision guiding this non-museum: “We believe that things like art history and individual artist intention are interesting and important, but only when paired with other voices and approaches that remind us that art, after all, is created and consumed by real and complex people whose motivations are mostly obscure, even to themselves.”

The conservative cultural and literary journal Quadranthaa radically differentopinion: “MONA is the art of a tired and declining civilization. The lights and special effects illuminate a moral bankruptcy. What is put in their spotlight blends seamlessly with contemporary fashion, design, architecture and film. It is an expensive and strained decline.”

|

| Nolan Snake at MONA. Photo from https://miifotos.com |

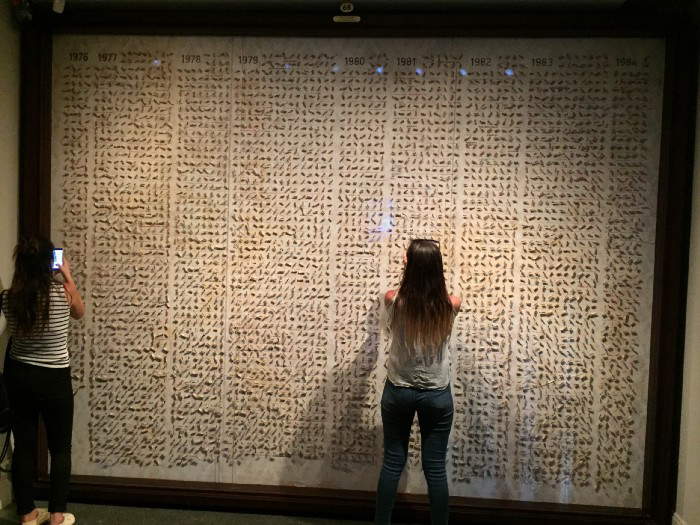

Another non-museum that is now perfectly assimilated into the museum landscape is Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence in Istanbul. This may be the first museum born in fiction and created in the real world. The novel and the museum share a collection that they share through their fiction, whether written or displayed.

Of the museum and the novel can be experienced independently, and the museum’s website is very clear on this point: "The museum presents what the characters in the novel used, wore, listened to, saw, collected, and marked, all meticulously arranged in boxes and display cases for exhibition. It is not essential to have read the book to visit the museum, and likewise it is not necessary to have visited the museum to fully enjoy the novel. But those who have read the novel will better grasp the many connotations of the museum, and those who have visited the museum will discover different nuances they missed by reading the book."

Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence has been much better absorbed into the museum landscape than MONA, but both can be defined as non-museums, conceived on the periphery of the museum world, where innovation continues to take shape. And this, too, is an interesting example of transmedia thinking where museum forms go beyond the physical.

|

| The Museum of Innocence. Photo from https://robertpimm.com |

So, what should be the ambition of the non-museum or non-artgallery?

I am fully aware that to choose an answer to this question is to risk simplifying the complex identity of these kinds of museums. But I could think of at least two strands of critical thinking about the non-museum that can guide us in the moment we are living even though there are certainly more elements to explore, define and analyze.

Meanwhile, they should aspire to connect different art forms and challenge art history classifications that have been in place for decades if not centuries. This happens all the time in temporary exhibitions, but permanent exhibitions remain somewhat removed from these kinds of developments. The digital, the virtual and the physical often remain separate exhibits. This thinking is feasible even for traditional museum forms, those perhaps best suited to the current definition of a museum. I tried to dispel this myth at the Malta Land of Sea exhibitionat the BOZAR center in Brussels in 2017. This project blurred the distinctions between artworks, as the photo shown below demonstrates. Videos, oil paintings on canvas, works on paper, and a mirror image of a seventeenth-century drawing by Dutch artist Willem Schellinks have been incorporated into a single narrative capable of crossing mediums. There are indeed images that are physical, virtual but also reflected. In my curatorial practice it is the image that counts: the rest is often shaped based on parameters conceived within a value system created by the art market.

|

| Malta Land of Sea |

Then, the ambition should be to recognize the universality of cultures that instead are often separated and caged in separate museums, which sometimes celebrate nationalistic narratives and nation-state ideals, and where we continue to focus on enduring and entrenched art-historical narratives. These continue to be included in Artsy’s list of the most talked-about and beautiful new museums of 2019, in MuseumNext’s list of new museums of 2019 for which MuseumNext exalted, and in Lonelyplanet’s top10 museums and art centers opening in 2019.

In short?

Non-museums are the vanguard of a necessary, essential and fundamental rethinking of the museum world. They are a necessity now more than ever as part of a quest to define the museum, the outcome of which seems more difficult than ever to achieve. Non-museums lead us to think about the museum differently, which would also be a necessity in the post-COVID19 world.

They are not easy to find and avoid recognizing any preconceived definition. And in fact their raison d’être is often to question that definition--and we certainly need them to do so. Do you know any of them?

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.