All those who visited Cremona’s Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone” this winter could not help but have an incomplete experience, probably unsatisfactory for many, since Cremona’s best-known museum, from late October to early February, found itself without its two main and best-known masterpieces: Giuseppe Arcimboldi’sHortolanus and Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Meditation. Both were temporarily out of their locations because they were on loan to temporary exhibitions, namely the one on Arcimboldo in Rome’s Palazzo Barberini and the major Milanese monograph on Michelangelo Merisi at the Palazzo Reale: two exhibitions that could easily have dispensed with the two Cremonese works without affecting the scientific and popular project. Needless to say, the institution’s reputation has suffered somewhat from such a situation: one only has to scroll through the museum’s page on Tripadvisor to come across a number of reviews from visitors disappointed at not being able to view the two works.

That of the Cremona Civic Museum is far from an isolated case. On the contrary: more and more often many museums, especially medium or small ones, lend their most iconic masterpieces, depriving themselves of them even for long periods of time, and more and more often works of fundamental importance within a collection leave for exhibitions of little value, if not totally lacking in scientific character: we saw this, for example, last year, when the central compartment of Piero della Francesca’s Polyptych of Mercy, kept at the Museo Civico in Sansepolcro (and let us remember that a 15th-century panel is a very fragile object: when faced with moving a painting, one must also come to terms with its physical nature), was brutally removed from the rest of the structure and sent to Palazzo Marino, in Milan, for a squalid and mortifying Christmas display. In return, the city of Sansepolcro had obtained the collaboration of the City of Milan to mount two exhibitions, scheduled for this year.

In fact, many loans arise from cultural exchanges that those involved aim to establish. One of the latest examples in this regard is the loan of Guido Reni’s Slaughter of the Innocents, perhaps the most famous work in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, which left Emilia for the Château de Chantilly, France, to be displayed in an exhibition that compared a number of works by artists from different periods on the theme of the Gospel episode: the exhibition was held from September to January, and the Bolognese museum had obtained in exchange the loan of one of Guido Reni’s most representative works, the Nessus and Deianira from the Louvre, which would be housed in the rooms of the Pinacoteca for the same period as the Chantilly exhibition (and some newspapers wrote, moreover, that the Nexus and Deianira would “return home,” but in fact the home of the Rhenish masterpiece is indeed the Louvre, since the work was acquired by Louis XIV as early as the mid-seventeenth century). However, one has to wonder to what extent such a practice can be considered acceptable: continuing with the same example, the Massacre of the Innocents had already been on loan from December 2016 until March 2017 for the exhibition The Universal Museum in Rome, and on its return from Chantilly it would stay for an additional month in Aosta. In essence, in the span of fifteen months, the most celebrated masterpiece of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna spent about ten away from its home. Did the absence produce benefits? Were the disadvantages or advantages greater? Is it an experience that will be repeated? These are questions that should be pondered.

|

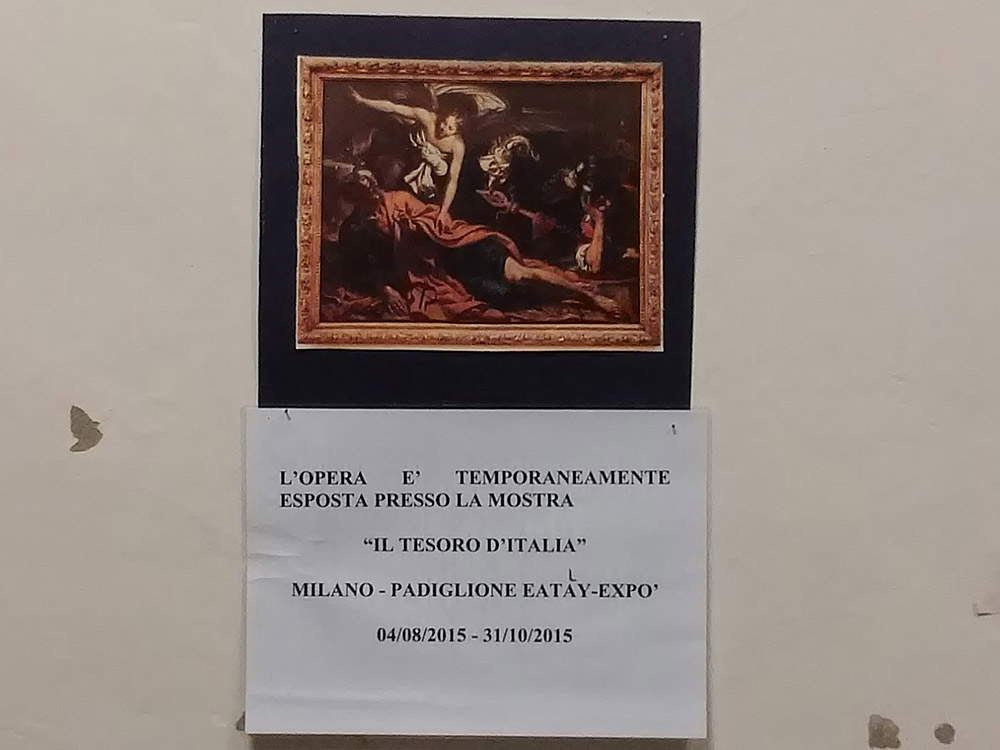

| A sign indicates the absence of Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri’s Saint Peter in Prison from its wall at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino in 2015: it had been loaned for Sgarbi and Eataly ’s exhibition at the Milan Expo |

And perhaps it is not even necessary to reiterate that the exchange should still be based on sound scientific grounds: it therefore becomes hardly acceptable to know that, in November 2017, three Caravaggio paintings from the Galleria Borghese in Rome (out of six) left, amid general silence, for Los Angeles, where they stayed for three months, for a scientifically useless exhibition, but which was part of an agreement with a fashion maison to publicize the project of a “Caravaggio Research Institute,” an international center for studies on Caravaggio, whose project appears, however, rather vague, at least at the moment, and whose promotion, for some bizarre reason, absolutely had to start in California. One must then consider the fact that ancient works of art are extremely delicate objects, and no matter how safe their handling is now, there is always the risk of something going wrong: the case of Bernini’s Saint Bibiana, loaned to the exhibition on the great Baroque artist at the Galleria Borghese, and ended up with a broken finger during the relocation operations in the church (which is three kilometers from the exhibition venue: a perhaps untimely loan, whose only justification lay in the fact that the work had been restored for the exhibition), should put everyone on alert.

Even churches, after all, are not exempt from the problem of all-out loans. One thinks of Caravaggio’s Madonna of the Pilgrims, a work made for the church of Sant’Agostino in Rome and still kept there: in the last year alone it has left its chapel twice, and always for exhibitions from which nothing would have detracted from its eventual absence (the monographic exhibition on Caravaggio at the Palazzo Reale, and the exhibition onEternity and Time from Michelangelo to Caravaggio, in Forlì). The same goes for Pontormo’s Visitation preserved in the parish church of Carmignano, near Prato: also out twice in the space of a year, for the exhibition on Bill Viola at Palazzo Strozzi (where it could have been replaced by a reproduction, partly because of the fact that Bill Viola, for his work The Greeting, did not meditate on the original), and for the exhibition on Pontormo at the Uffizi.

What, then, is the right balance? Can a small museum deprive itself of its masterpiece if it can gain concrete benefits in return? On what basis should a cultural exchange between two institutions be based? Shouldn’t every museum have a list of works that are immovable, or can be moved only for more than solid reasons? Francis Haskell, the critic “who detested exhibitions,” as per Pierluigi Panza’s icastic definition a few years ago, was convinced that the only justifiable moves were those that were useful, where usefulness is to be measured solely on a scientific basis. So perhaps it is time to open a discussion about lending policies and the way we regard works: too many times we have witnessed the trampling of every good practice of art history, and it is therefore necessary for works of art to return to the center of reflection. These are topics to which, surely, we will return shortly with some proposals.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.