Is it right for a seminal masterpiece by Pietro Lorenzetti to fly from Arezzo to New York?

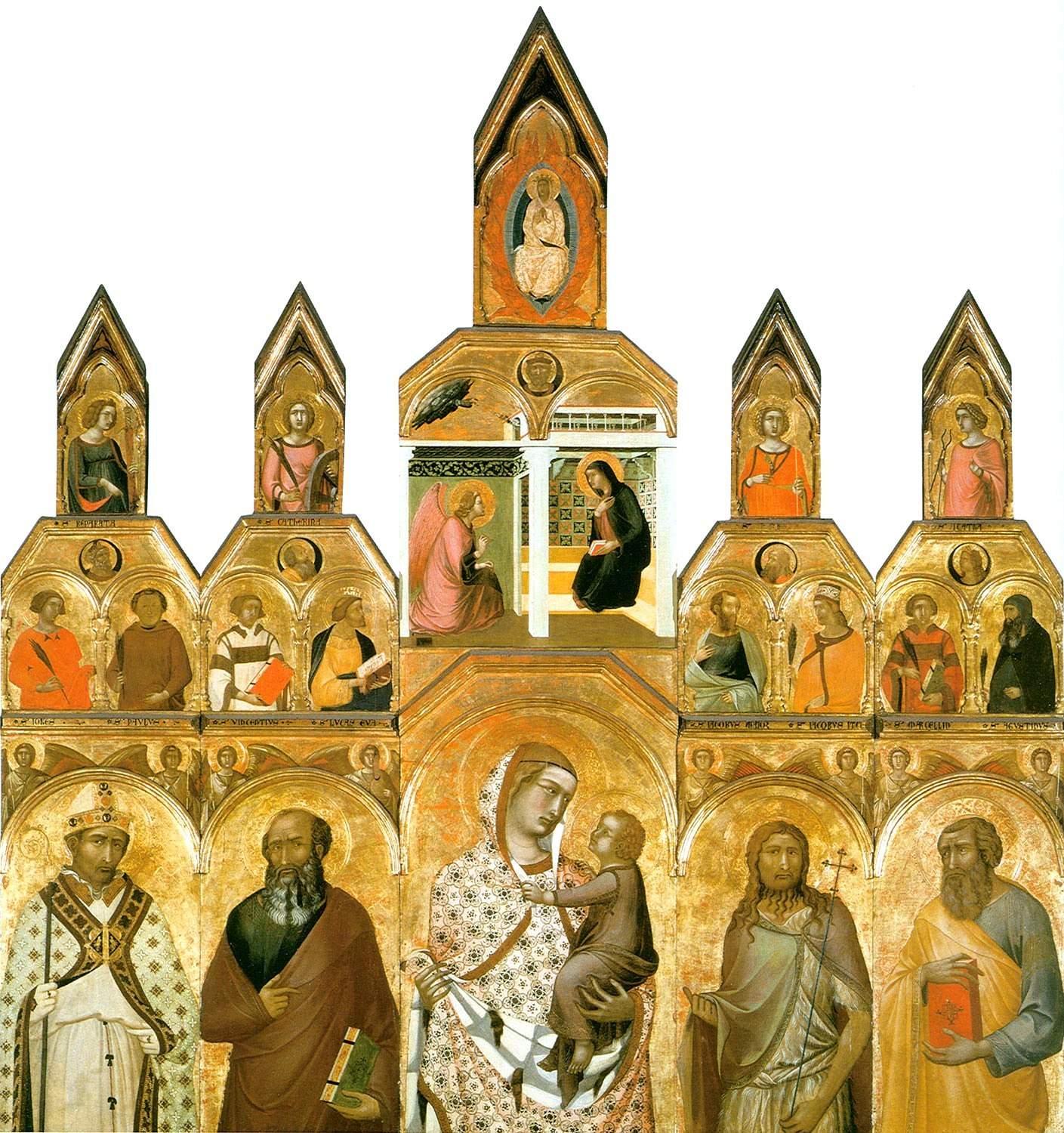

Giorgio Vasari also speaks of the Tarlati Polyptych, a masterpiece by Pietro Lorenzetti that since 1320 has never moved from the site for which it was painted, the church of Santa Maria della Pieve in Arezzo, in his Lives: in Vasari’s compendium is “the panel of the high altar of the [...] Pieve, where, in five pictures of figures as large as the living man’s knee, [Lorenzetti] did Our Woman with the Son in her arms, and St. John the Baptist and St. Matthew onone of the sides, and on the other the Vangelist and St. Donatus, with many small figures in the predella and above in the fornimento of the panel, all truly beautiful and conducted with bonissima maniera.” Vasari was also familiar with the work because it was he who oversaw the remaking of the altar above which the polyptych is placed, as well as the restoration of the entire church of the Pieve, one of the oldest, most important and complex churches in the historic center of Arezzo, a church to which Vasari himself was very fond by his own admission, having attended it since childhood.

And in the very year of Vasari’s celebrations, in the year in which we commemorate anniversary number 450 of Vasari’s death, in the year in which Arezzo revives the memory of its artist with a long schedule of exhibitions, the public, for several months, will see stumped the church to which Vasari was so attached, because the Tarlati Polyptych left a few days ago for New York, where an exhibition on the arts in Siena in the fourteenth century(Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350), which will then be moved to the National Gallery in London for the second leg, scheduled from March to June 2025. We said that the Tarlati Polyptych, also known as the Polittico della Pieve, one of Pietro Lorenzetti’s major works, has never moved from its church. It has always remained in place, restoration permitting (it has only been removed during the maintenance work it has had to undergo, the last in 2020: we are still talking about a work that is seven hundred years old). It is a work of capital importance, one of the cornerstones of Pietro Lorenzetti’s production, one of the references for the reconstruction of the vicissitudes of the arts in Siena in the early fourteenth century, one of the symbols of Arezzo, as well as one of the most documented works of its time: it was commissioned by the then bishop of Arezzo, Guido Tarlati, who called the Sienese artist to Arezzo (we are left with the contract of allogation of the work). This is therefore the first time it has been lent for an exhibition, and its debut will take place overseas, several hours’ flight from its natural home, from the place where the Tarlati Polyptych has always remained. Now, in short, it will no longer be possible to say that that work has never left its natural home, the place for which it was made. And all this for an exhibition built primarily around the collector cores of the Metropolitan Museum and National Gallery, and thousands of miles away from its context. It is as if Siena were to organize an exhibition on the Impressionists: it may be an obviously excellent and thorough review, but it will never have the same value as an exhibition on the Impressionists organized in Paris, where Impressionist painting was born, in the midst of the places the Impressionists frequented, close to the museums that preserve their fundamental masterpieces. The same applies to an exhibition of fourteenth-century Sienese art held in New York.

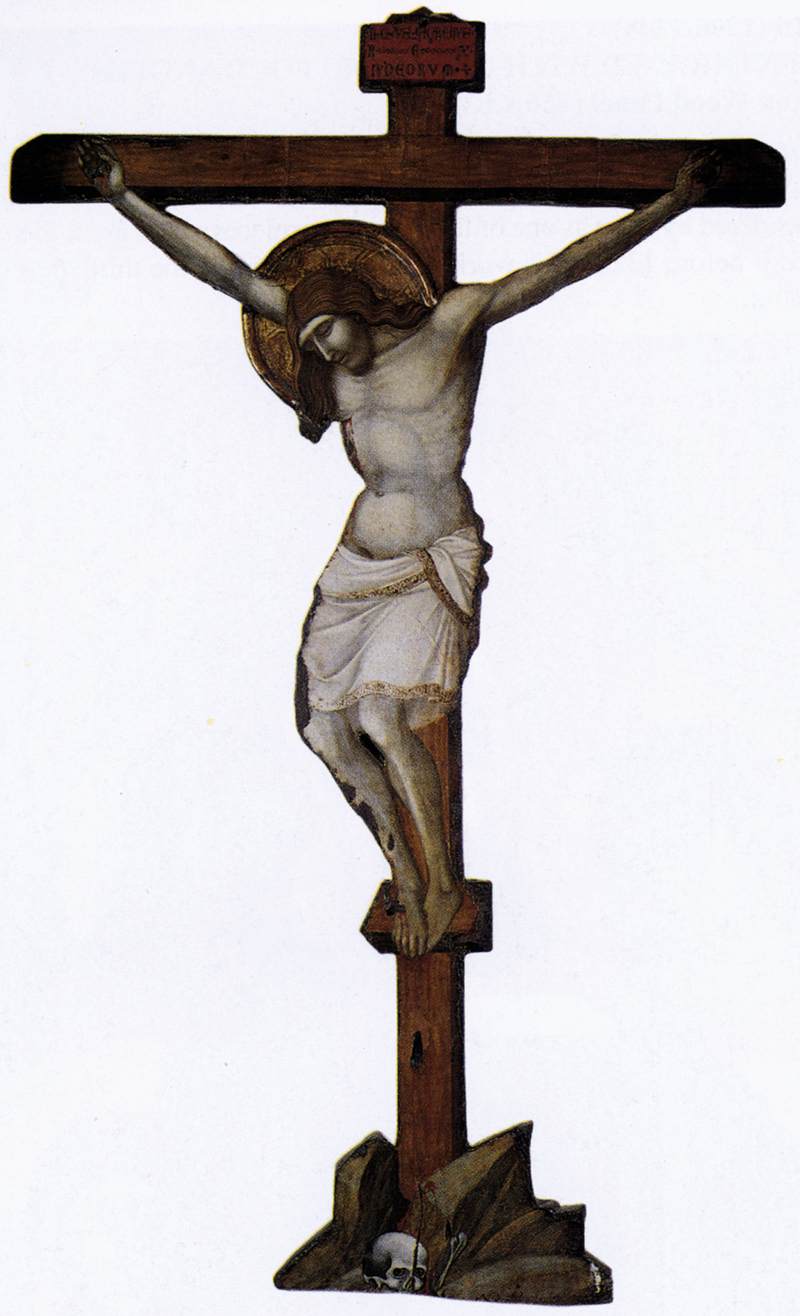

The Tarlati Polyptych is then not the only other “Arezzo” work by Lorenzetti exhibited in New York. From Cortona, in fact, his Shaped Crucifix also left for the United States. The decision for both loans was made by the Diocese of Arezzo, following negotiations with the Met that started as far back as 2019, although nothing leaked out for years: only this summer, in some articles that appeared in the American press, did a photograph of the Pieve Polyptych begin to circulate (without, however, being mentioned as part of the exhibition), and only after the overseas trip had now taken place was the news given proper prominence. In exchange for the loan of the two works, the Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery in London secured funding for the restoration of the Transit of St. Joseph by Lorenzo Berrettini, a work from 1662-1672 kept in the Co-Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Cortona.

Long gone are the times when, a short distance from Arezzo, the inhabitants of Monterchi, in the 1950s, refused to send Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto to Florence for an exhibition. And the days when Cesare Brandi lashed out at the Monterchi administration for deciding, it was 1983, to lend Piero della Francesca’s masterpiece (curiously enough, always to the Metropolitan) in exchange for resources intended to improve its exhibition conditions also seem long gone. Today no one raises the slightest objection if a key masterpiece by Pietro Lorenzetti, a work never removed from its church except when strictly necessary for its survival, is boarded on a plane and sent overseas in exchange for the restoration of a work by Lorenzo Berrettini.

Many are then the questions that such an operation raises: if even a work, such as the Tarlati Polyptych, which has extremely rare characteristics (i.e., a polyptych executed by one of the great names in the history of Italian art, well preserved, documented like few other works of its era, strongly linked to its territory, and never left its natural home), is deemed lendable for an exhibition that on paper does not appear to be essential, then does it still make sense to speak of immovable works? Is it proper for two such important works by Pietro Lorenzetti to be loaned for so long (almost a year) in exchange for the restoration of a work by Lorenzo Berrettini? Hadn’t local lenders been found? Is a restored Lorenzo Berrettini worth two trips, one to New York and one to London, of two Pietro Lorenzettis, one of them crucial? Are we still convinced that lending an important work lends luster to the city from which the work departs? Or is it the other way around? That is, is it not, if anything, a boast for the Met? Besides, isn’t depriving Arezzo for almost a year of one of its most important works, and in return for so little, tantamount to impoverishing the city?

The best answer, for now, is perhaps the message that the exhibition’s curator, Caroline Campbell, sent to Arezzo Mayor Alessandro Ghinelli: “Dear Mayor, we can breathe a sigh of relief. All five panels are safe in our warehouse. They arrived shortly after midnight.” Lo and behold, if it is necessary to stand by with bated breath while a seminal masterpiece by Pietro Lorenzetti, never moved from its location, is on its way from Arezzo to New York, it means that perhaps we need to think very deeply about the casualness with which capital works of art are lent.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.