Inside Michelangelo Pistoletto's resonance chamber.

There is an advertising poster from the 1980s, the advertisement for an American hairspray, in which Andy Warhol can be seen holding a spray can in his hands, albeit with a certain concentration: he is wearing his typical dark turtleneck, he is wearing his typical blond wig, he is fixing his eyes on us looking at him, and above him is the slogan: “Vidal Sassoon Natural Control Hairspray for men - the art of style.” We can all agree that the label of the artist as a brand of himself, the artist as a brand, sticks to Warhol more than to others: a label that Andy Warhol tried to keep sewn onto himself obsessively throughout his career by building around his figure, with engineering precision, a well-marked public identity. It was not just a matter of presenting recognizable art to the public, an end to which any artist usually tends. Andy Warhol transformed himself into a brand by acting on several fronts: he made his art, through seriality and by fishing his subjects out of popular culture, a commercial product. He constructed a precise public image of himself, enigmatic and recognizable: the same wig, the same expression, the same clothing, the same way of life. He tried to remain in the spotlight as much as possible. So many later would follow her example.

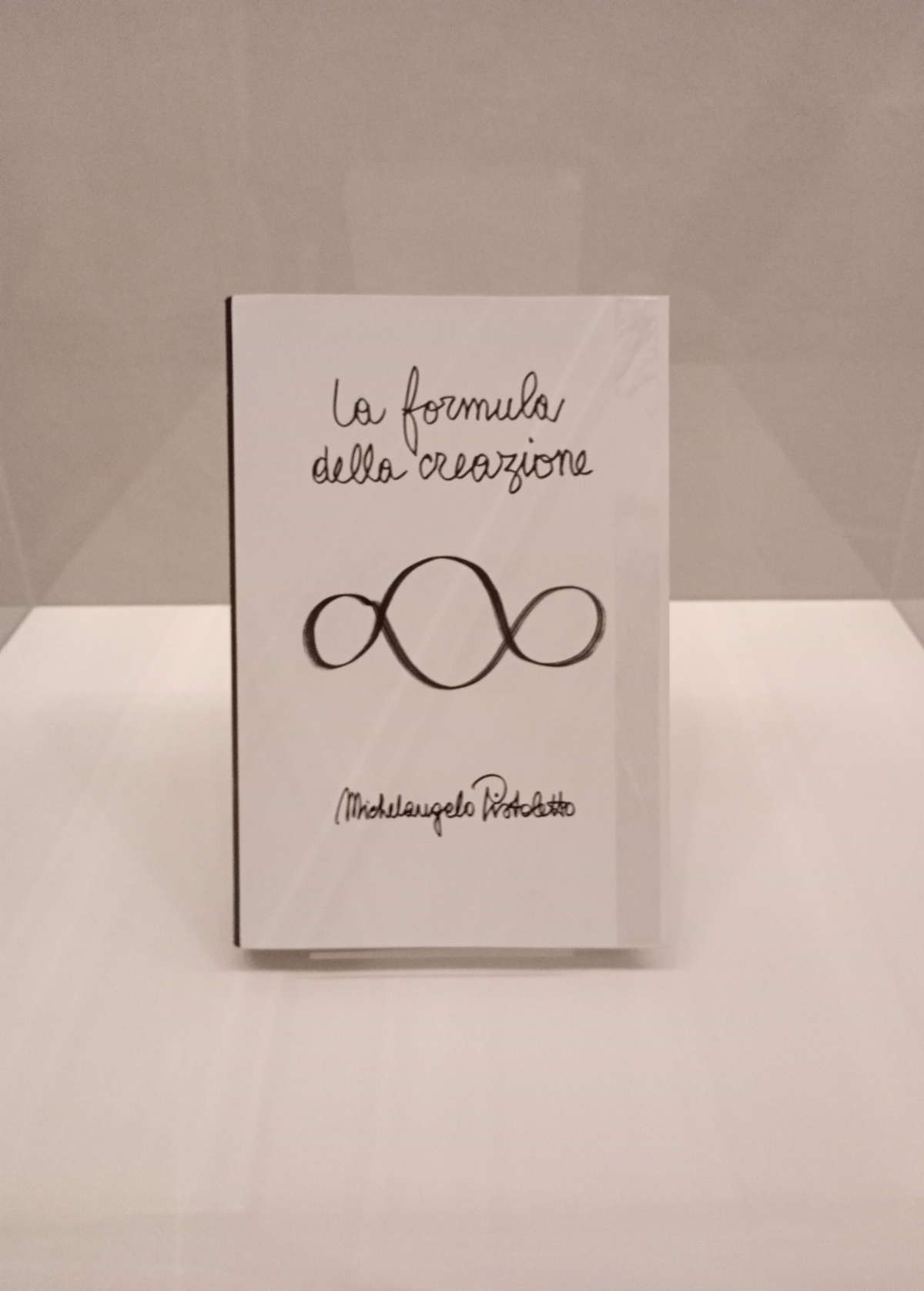

Today, at least in our parts, the artist who in this sense comes closest to him is probably Michelangelo Pistoletto, despite the fact that Pistoletto has repeatedly shunned any juxtaposition with Warhol. Pistoletto is also an artist whose works are marked by a certain regularity, if we do not want to use the term “seriality.” Pistoletto, too, has built an unmistakable image: the guru aura, the well-groomed white beard, the clothing always on black, the inseparable fedora. Pistoletto, too, is a devotee of presentialism: he is seen on television with a frequency unknown to virtually all other living artists, with the interviews he has given one could fill a library, there is no event about him at which he does not appear in person (he has an enviable energy, it must be said), he organizes flurries of exhibitions. What’s more, compared to Warhol, Pistoletto also has his own logo, the Third Heaven, which has now become a kind of graphic expression of his personality. He may have shied away from arguing with Warhol, as he stated in one of his countless interviews, because he was interested in “fighting imperialism in art,” but Pistoletto, too, has, over time, become a brand. Let it be said, of course, without any tinge of outrage, far from it: Pistoletto is an artist who has managed to do things around his person that the vast majority of his colleagues are precluded from doing. And still, the presence of recognizable artists at a time in history when art appears increasingly irrelevant is positive.

The brand ’s reputation will inevitably benefit from the recent “nomination” for the Nobel Peace Prize, which Pistoletto immediately welcomed willingly, although seeing it, he said, “not as a personal recognition for what I have done so far, but as a commitment to future work.” A commitment, the press reports, “to peace, social justice and collective responsibility.” Now, it is not so much the news of the nomination itself that is of interest, but if anything the very fact that the Third Paradise has been recognized, for some reason, as having such a current and relevant dimension that Pistoletto’s candidacy for the Nobel Peace Prize is serious and well-founded. The artist from Biella has been taking his project around the world for more than 20 years, understanding art as a means of social transformation, as a means of building a collective responsibility that aspires to create a more sustainable and peaceful world. His Third Paradigm is, by ’statutory’ definition, shall we say, the “phase of humanity that is realized in the balanced connection between artifice and nature,” the “transition to an unprecedented stage of planetary civilization planetary, indispensable to ensure humankind’s survival,” a stage of our common existence that aims to reform ethical principles and behaviors that guide our societies. Since 2003, the definition has not changed one iota.

Pistoletto’s Third Paradise has gone through the Second Gulf War, the birth of social networks, the Orange Revolution, the Arab Springs, the Great Recession, the sovereign debt crisis, the attacks by theIsis, the migrant crisis, Obama’s and Trump’s double inaugurations, Covid, the assault on Capitol Hill, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, the war in Ukraine, the war in Gaza, the advent of artificial intelligence. The world has changed, but Pistoletto’s Third Paradise has remained the same. Always the same. Always the same logo re-created with whatever medium comes to hand: stones, hedges, trees, neon, metals, textiles, T-shirts, furrows in the wheat, the ever-present roundabouts. Always the same Third Paradise. All around, the world has been turned upside down. We have all changed. Everyone except Pistoletto. Who has never stopped proudly flying the flag of his naïve and purely idealistic pacifism. As the world moves on, the Third Paradise seems as if trapped inside a parallel universe in which the 1970s never ended. Back in 2003, when Pistoletto founded the Third Paradise, the idea that the world could be changed through great collective utopias seemed at least anachronistic. Let alone today, in a liquid, fragmented and uncertain world: those who call for concrete actions, direct engagement and stances are answered with the abstractionism of quantum leaps in planetary civilization.

In theinterview with Corriere that accompanied the announcement of his candidacy, Pistoletto, despite all his commitment to peace, also succeeded in the feat of entrenching himself behind a “no comment” to questions about the war in Ukraine and Italy’s position in the context of the crisis we are experiencing. The Third Paradise does not mix with the contingent: it is one of his prerogatives, a choice that is certainly always claimed, but at the very least it is out of date. To those who ask Pistoletto for a stance, he responds by saying that the Third Paradise is not “political” but an “alternative practice.” Today we risk a peace in Ukraine closed on unsustainable terms, which would smack of surrender and capitulation in the face of a Russia that is moreover in the throes of a crisis, and would risk projecting us into a future of even more serious and unsustainable tensions. We are at a time when the roles of the invader and the aggressor have come to be reversed. We have a U.S. president who even goes so far as to insult what should be his ally, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelen’skyj, not hesitating to call him a dictator and to say that his presence at the negotiating table is useless. There is the prospect of a reorganization of the structure of Euro-Atlantic relations in ways that may not be ameliorative and may even push away that very “preventive peace” that Pistoletto called for. Here, in this context, how current can it be to continue with the roundabouts of followers? How topical is it to disconnect from reality by refusing to take a position regarding real conflicts? How current is it to preach to one’s choir, to sensitize those who are already sensitive, to put oneself in lockdown inside one’s own resonance chamber?

So, is the Third Paradigm as a method of promoting peace an initiative with concrete impact, comparable to the efforts of so many who have won Nobel Peace Prizes in the past, or is it, if anything, an artistic exercise aimed basically at those who already share the values of the Third Paradigm, and linked to a worldview that was relevant when Pistoletto was young? The problem is that today the transformative power of art is not what it used to be, because the world is no longer what Pistoletto experienced fifty years ago: today we live in a fragmented context, saturated with stimuli and information, including visual information, and the impact of art depends on how art fits into the real social and political fabric. To say, a work of redevelopment of a degraded urban context, or a company that invests to restore a work to which a community is attached or to refit a local museum, are actions with a more concrete impact than a Third Paradise in the halls of the Royal Palace. Of course, under the brand of the Third Paradise, it will be said, concrete actions have also been done in the local area (food education initiatives in schools, workshops on the issue of environmental sustainability, meetings in hospitals and more): one certainly does not dispute the usefulness of these actions. What is contested is the fact that the narrative framework of the Third Paradigm, in addition to being a superstructure (there are many entities that pursue social utility without aspiring to move towards unprecedented stages of planetary civilization by carrying around logos, there are myriads of citizens who feel the need of an assumption of responsibility without the need for a symbol), if it avoids involvement with the contingent, or with “politicking” as Pistoletto calls it, it remains a pure conceptual exercise.

Then we return to the work of art: if at this historical moment a work that aspires to have an impact on society carefully avoids taking a position on what is happening in the world (always assuming that today the possibility of an art capable of having a real political impact can be given), lo and behold, that art ends up, on the contrary, by excluding itself, by limiting its impact to those who are already sensitized. Which is not to say that it is not a prospect, there are those who do so consciously, there are those who believe, for example, and legitimately, that the refuge in the everyday can be an answer to uncertainty (indeed: it is an answer even more practical, direct, comprehensible and incisive than the transition to the more evolved stage of planetary civilization). The hypersentimentalism of so much contemporary art arises as a reaction, if you will, also political, to the fragmentation and liquidity of our society, and it is also much more interesting, concrete, and topical than a Septuagint ideal. Or a logo.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.