If we feel touched on fascist monuments, perhaps we still have some unfinished business

Finding a single answer to the question launched by the already widely discussed New Yorker article signed by Ruth Ben-Ghiat, who wondered why so many monuments of the Fascist twenty-year period still exist in Italy, is a virtually impossible task, since it would be necessary to trace the history of each of the individual vestiges of the regime that still remain intact. To answer the question, however, one can start with a necessary historical premise: in Italy, defascistization advanced in a rather confused and chaotic manner, and without responding to any systematic coordination, with the consequence that the process encountered not a few difficulties, failed to be truly incisive (also due to the fact that many functionaries involved in the defascistization, which was supposed to cover all aspects of the public sphere, from schools to the administration, from the army to the judiciary and so on, were themselves implicated with the regime), and on the political level experienced a major setback with the Togliatti amnesty to the point that, according to the vast majority of historians, the outcomes were all but unsuccessful.

The same lack of organization, combined with contingent situations, could be cited as one of the reasons why many accounts of fascism still make a fine showing today. It must be stressed, however, that Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s article starts from a rather fallacious premise, since the author includes, in the broader category of"monuments," as much buildings as statues, tombstones, and perhaps evenodonomastics, given that the scholar wonders why France changed the names of streets named after Marshal Pétain while “Italy allowed its fascist monuments to survive undisturbed.” Assuming, of course, that even in Italy there are no longer any streets or squares with names that can be traced back to Fascism, it is necessary to remember that throughout history, successive regimes and civilizations have always preferred to reappropriate pre-existing buildings rather than erase them. A building may be clothed with symbolic meaning, but it also has a practical function: remove the symbol, the practical function remains (an assumption that does not apply to statues and tombstones). Add to this the fact that, at the time, Italy was emerging devastated from a world war that had left behind rubble everywhere, which is why the economic resources available to the country at the time were used to rebuild, rather than demolish. The work of reconstruction that also passed through the buildings of the regime, with all that came with it (about the reuse of the Eur monuments, a staunch opponent of fascism such as Bruno Zevi wrote, with biting sarcasm, that "at a fifth of five-story-high pillars, designed to frame military parades after the occupation not only of Paris and Alexandria, but also of Cape Town and Beijing, one can read a sign: pastry shop or diner"), necessarily involved that reappropriation which is a typical trait of art history and architectural history, achieved through more or less refined steps.

One of the most distinguished historians of Fascism, Emilio Gentile, has advanced a comparison with wars of religion (in this sense, the Pantheon is, moreover, one of the most illustrious examples of reuse): "a whiff of religious ritual was present in the symbolic defascistization of Rome, as it had been present in the symbolic fascistization of the capital and in the monuments of Mussolini’s new Rome, the stone Fascism, in which the myths of Fascist religion materialized. As in any religious war, even in the war between secular religions, the religion that emerges victorious erases the symbols of its defeated rival, and if it cannot erase them, it baptizes them with new names and incorporates them into its own cult. This is what happened when anti-fascism supplanted fascist religion: the Ponte Littorio was incorporated into the antifascist religion under the name of Giacomo Matteotti, who was murdered by the fascists in 1924; to the young antifascist Piero Gobetti, who died in exile in 1926 after suffering repeated squadron assaults in Turin, Viale Libro e Moschetto was named near the university city, inspired by the pedagogical motto dictated by the Duce to fascist youth; Viale dei Martiri Fascisti was reconsecrated with the name of trade unionist Bruno Buozzi, who was shot by the Nazis in 1944. And by the law of counterpoise, the headquarters of the Ministry of Italian Africa became the headquarters of FAO, the United Nations Organization for Agriculture and Food." The same process of reuse (which is necessarily followed by a decontextualization that should in fact empty the buildings of all primal meaning) also affected Nazi Germany: the same “law of counterpoise” to which Gentile refers also affected Hitler’s buildings, such as the Führerbau in Munich, which from being the administrative headquarters of the regime became a sorting center, towards the countries of origin, of works of art stolen by the Nazis. But think also, very simply, of a fact well known to Italians, namely the 2006 World Cup soccer final that saw Italy victorious on penalties over France: it was played in that same Olympiastadion in Berlin strongly desired by Hitler for the 1936 Olympics. A couple of cases to highlight that the survival of buildings is a normal historical fact and should not be confused with the dismantling of statues, tombstones, plaques and inscriptions, an operation that is decidedly easier and presents far fewer practical and economic difficulties than the demolition of an architectural construction would entail.

|

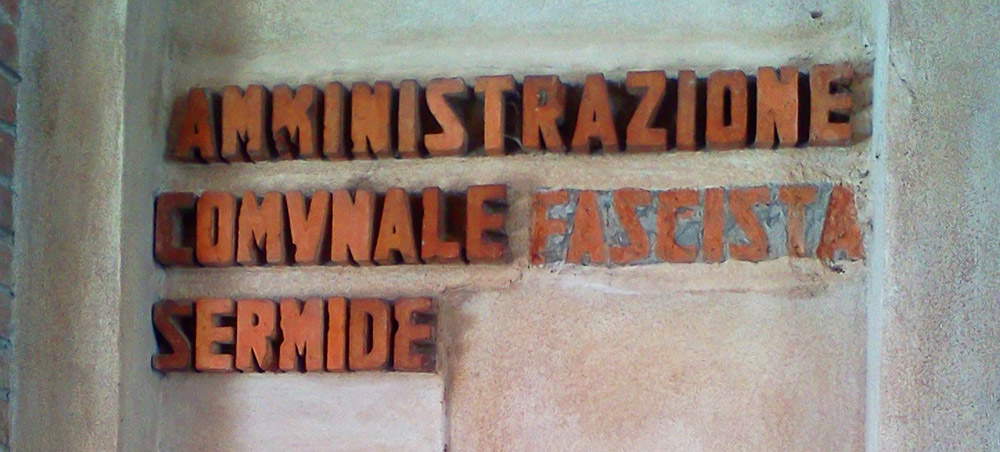

| Inscription on the Civic Tower of Sermide (Mantua) with the word “fascist” abraded. At the last elections in the small Lombard town, a list with the fascio littorio in the symbol entered the town council. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Nor was it a matter of aesthetic sensitivity aimed at safeguarding the major artistic eminences created under the regime, since the dismantling did not spare works by some of the most distinguished artists of the time: the so-called “Bigio” by Arturo Dazzi was removed and stowed away in a municipal warehouse in Brescia, the bust of Mussolini made by Adolfo Wildt that adorned the Casa del Fascio in Milan (and of which copies survive today) was destroyed, ironically, by blows from that pickaxe that had become a metaphor for the demolitions of entire neighborhoods that the regime put in place to renew the urban planning of the country, and again the precious interior decorations of the Casa del Fascio in Como, the work of Mario Radice and among the first interventions of abstract art applied to a public building, were also removed after the Liberation, and the Casa del Fascio itself, an architectural masterpiece by Giuseppe Terragni, would have been demolished in the 1950s, if a chorus of critics (including the aforementioned Bruno Zevi) eager to safeguard one of the greatest examples of Italian rationalism had not risen against the operation.

On the other hand, a large number of wall paintings and frescoes remained intact or almost intact, which, being inside buildings, managed to go virtually unnoticed and thus avoid the natural iconoclasm that followed the fall of a totalitarian regime. Or at most they were emended of the more conspicuous symbols. However, even conspicuous testimonies have managed to pass through the course of events unscathed. Take, for example, the large inscription that stands out on the facade of the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana at EUR, one that celebrates Italians as “people of poets of artists of heroes / of saints of thinkers of scientists / of navigators of transmigrators”: it is a phrase taken from the proclamation of the war on Ethiopia. And fixed on the facade of a monument with the triumphalism typical of the Ventennio. Or at theobelisk in the Foro Italico, a legacy that remained standing because the complex, in the midst of the war, was occupied by the U.S. Army, which, at the end of the conflict, reconverted it into a rest center for soldiers and then handed it over to the local authorities (the CONI headquarters was installed there) when, evidently, the removal of fascist symbols was no longer an urgent or priority matter.

Net of the basic misunderstanding and certain boutas that Ruth Ben-Ghiat indulges in (such as the “viva il Duce” episode at the pub, devoid of any argumentative character, but effective in appealing to the U.S. public), it is possible to consider the article not as a call for a resumption of the dismantling work (that would be ridiculous, and the author herself, in a subsequent interview, specified that that was not her intent: of course, the many accusations of renewed iconoclasm that have been levelled at her are nothing more than a misunderstanding bordering on functional illiteracy), but rather as an invitation to a reflection on our past and, above all, on the tensions to which that past still seems to force us: if an intervention such as Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s stimulates stymied responses, which misrepresented the message of the contribution and were more concerned with chastising the U.S. scholar for the ills afflicting her country (as if a foreigner has no right to express an opinion on what is happening outside her homeland) than with understanding the reasons that led her to write her piece, it evidently means that we have not fully come to terms with our past. Otherwise, it would not explain why, seventy years later, many people have not yet begun to consider those monuments as mere remnants of a bygone era, devoid of any political connotations referable to the present context, but full of historical significance from which to draw thoughtful and profound considerations. And, of course, we are not referring to those few who, having taken the path of a nostalgic Mussolinism, completely outdated but not without risks, believe that those symbols are still able to speak: the problem is more subtle.

If we want to trivialize, the decontextualization of fascist-era monuments risks, on the one hand, giving rise to a sort of mythicization that, far from bringing back a fascism similar to that of the last century (an eventuality that seems improbable and anachronistic, although certain recent current events should nonetheless give pause for thought), it could give rise to the idea of a past grandeur of Italy that was such only in appearance but that still tickles the instincts of populist political groups or the ultra-right that, even without going through the rereading of monuments, appeal to the emotional base of their respective electorates (and Ben-Ghiat herself fears, not entirely wrongly in the opinion of the writer, the return of a new fascism, under different forms: the same goes for other observers), while on the other hand, avoiding addressing the problem is tantamount to severing ties with history, an equally dangerous operation. What attitude to take, ultimately? For new symbol-removal campaigns, we are now out of time. What is needed, if anything, is an awareness of the problem. And above all, it is absolutely necessary to insist on education and didactics, reflecting on targeted commentaries, on exhibition routes, on documentation and research centers, on school curricula, on exhibitions and museums that can offer us concrete help to face with greater serenity a thorough reflection on our recent past. And the effectiveness of an effort aimed at critically rereading our past and averting the risk of new fascisms will obviously be greater if there is a policy capable of putting people at the center of its work.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.