One could turn a blind eye to the first proposal of the new president of the Fondazione Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, actor and comedian Luca Bizzarri, who at his inauguration last week proposed moving Paganini’s violin from Palazzo Tursi to Palazzo Ducale: an idea that, moreover, was well received by the City Council through the mouth of the councillor for culture and territorial marketing, Elisa Serafini, who asserted that “its valorization can pass from a change of location but also and above all from a sponsorship by a private entity through an annual disbursement.” Patience, then, if at the first useful opportunity the attention has been catalyzed by a single work, and if the idea (improvised, in the opinion of the writer) is to remove it from a museum itinerary where the “Cannon” (this is how the instrument is called) is exhibited together with other objects that create a logical and coherent path around the figure of Paganini, to exhibit it as a fetish in the Ducal Palace.

|

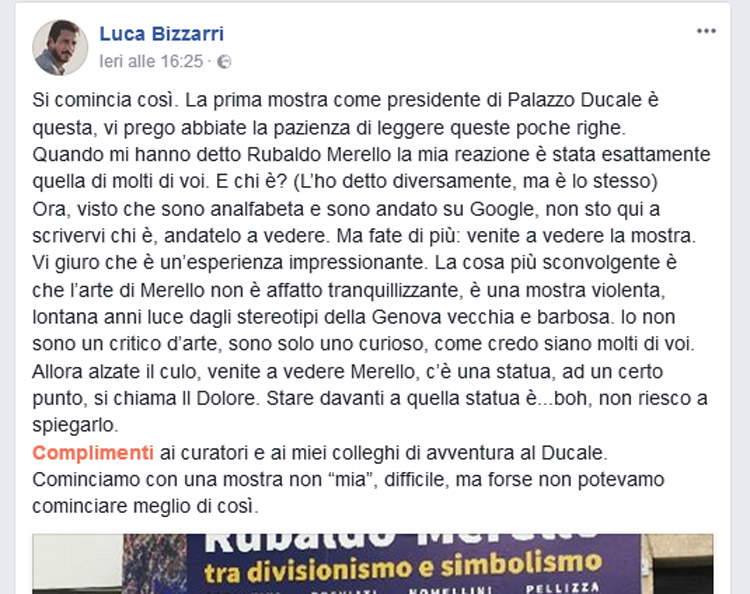

| Luca Bizzarri’s first Facebook outing as president of the Ducal Palace. |

If, however, in not even seven days as president of the Doge’s Palace, Luca Bizzarri adds another not-so-pleasant performance to his resume, questions need to be asked, at the very least, because his first virtual outing inherent in his institutional role (a Facebook post to present the monographic exhibition dedicated to Rubaldo Merello), poses a serious image and communication problem. And the problem is not so much his old-fashioned way of communicating, with that faux-youthful tone that is now tired and could have been fine or current perhaps in the 1990s: it is not up to him to communicate, although the image of the Ducal Palace also passes through the outings of its president, as is obvious and right. The problem is not even in that invitation, “get off your ass, come and see Merello,” certainly not at all suitable for the figure who presides over the foundation responsible for managing Genoa’s best-known and most frequented cultural institution, but in the face of which we might also be willing to pretend nothing if placed at the conclusion of a text that is pregnant with content. The problem is precisely the content.

Starting with the claim of his own ignorance: it is totally understandable that the president of the Ducal Palace does not know who Rubaldo Merello is. His job is not to know about nineteenth-century painting. Less understandable is the fact that such ignorance is flaunted, and filled in just by a Google search. In an age when the claim of ignorance is a political issue and anti-intellectualism becomes a kind of manifesto around which groups and movements rally, an attitude such as that of the President of the Doge’s Palace is at least imprudent on the mere political level, and totally inappropriate on the cultural one: if such a display of ignorance comes from one who has been called to preside over one of Italy’s most important cultural institutes, one almost has to fear for the continuation of Luca Bizzarri’s work, all the more so since, in concluding, he specifies that his presidency begins with an exhibition that is not “his” (however much the possessive is included in quotation marks). The president, by statute, is not supposed to be in charge of scholarly programming, so we would not want that possessive adjective (which, let us point out, in a Facebook post with such a blatantly mouthy tenor carries very little weight, but is nonetheless something to pay attention to) to open up unedifying role confusions.

But that’s not all: the cultural weight of the exhibition appears to be delegitimized the moment Luca Bizzarri does not invite the public to “get off their asses” so that with the exhibition they can discover or rediscover an important figure of pointillism in Italy, or because Merello’s works are placed in dialogue with paintings and sculptures by artists contemporary to him in order to reconstruct the art-historical context of the era in which he was active, or because he is an artist rooted in the territory and his tormented story unraveled in a period of strong tensions and disruptive social and economic changes, which obviously also affected the city in which the exhibition is held, or very simply because visiting such an exhibition is like granting nourishment to one’s critical thinking. No: the public is called to visit the exhibition because “it is a violent exhibition, light years away from the stereotypes of the old and barbaric Genoa,” and because there are works that leave one speechless. Leaving aside the fact that today Genoa is a city that is anything but “old and barbarous,” and that even stereotypes, by now, have been updated (unless one is constantly living inside a comedy sketch ), an exhibition should be an experience that, if anything, leaves one with many words and does not involve the audience only on the level of emotions: otherwise, from culture one moves on to mere entertainment.

I make no secret of the fact that I wanted to give Luca Bizzarri the benefit of the doubt when he was appointed to the presidency of the Ducal Palace this summer. And I continue to want to give it to him: a spic-and-span culture marketing idea and a stand-up comedian’ s exit may not yet be enough to doubt the appropriateness of his appointment. But it is time for Luca Bizzarri to begin to establish boundaries between his profession as a comedian and the institutional role he has been called to fill. The Ducal Palace would only stand to gain.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.