For a thoughtful reading of the 50 million visitors to museums: here are the real effects of reform

In the past few days, Minister Dario Franceschini has lavished, in decidedly emphatic tones, data on the influx of visitors to Italian museums in 2017: we are talking about a record 50 million visitors who, last year, visited our state institutes, guaranteeing receipts that exceeded 193 million euros. Figures that had never been reached before: therefore, we do not want to deny the minister the fact of having set a record for visitors and revenues that had never been reached since the statistical surveys of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage began (and about which we are all happy). However, beyond simple triumphalism, which does not belong to us, it is more than ever our duty to contextualize the data in order to provide an interpretation that is as impartial and objective as possible, one that does not limit itself to uncritically reporting the graphs that come from the ministry’s statistics office and, vice versa, seeks to interpret them in order to verify whether the results are really due, as the minister declared at the beginning of the press release, to the Renzi-Franceschini reform, or in what ways the reform has actually conditioned visitor flows.

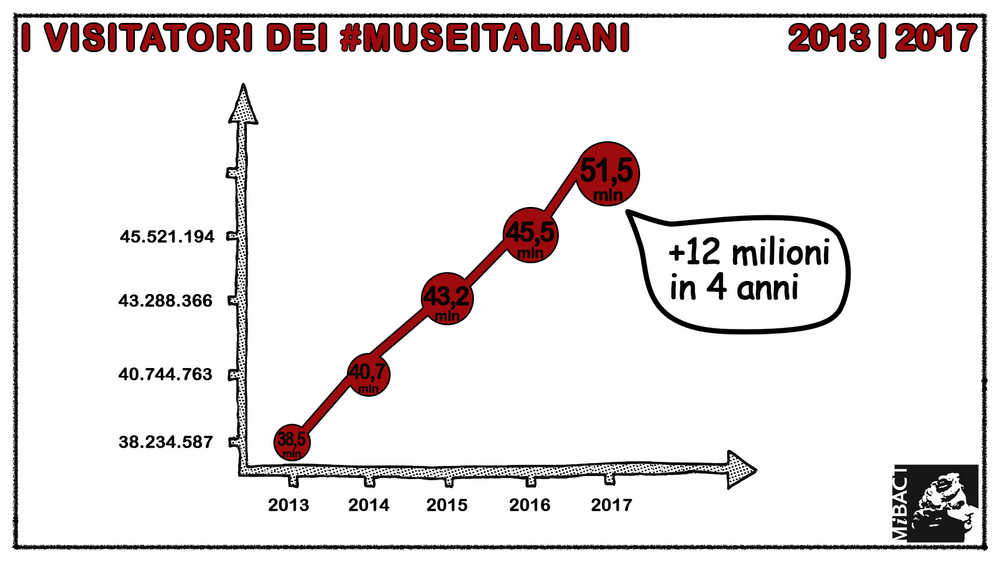

|

| Data on visitors to Italian museums in recent years. Image released by MiBACT |

Meanwhile, an initial challenge must be made to the data released in recent hours. In the press release, in fact, the number of the institutes that were surveyed is absent (we have asked and solicited this from the MiBACT statistics office, but we have not yet received a response): the data would have been extremely interesting to know the average number of visitors per institute. Assuming that more than half of the visits (about 27 million) are concentrated among the top 30 museums, and that this figure has experienced an increase of 7.74 percent over 2016 (almost two million more visitors in the “top 30,” 1,928,157 to be exact), the only operation that can be done, since the data released by MiBACT at the moment are partial, is to take a look at the trend by making a simple comparison with previous years. It will thus turn out that increases and decreases in “minor museums” (an ugly locution that, for convenience, we will use to refer to institutions outside the top 30), until the pre-reform years, were in some way linked to the results of the major museums, indeed: where the major museums increased or decreased, the minor museums made the results signify almost double rates. This was the case between 2008 and 2009 (-2% in major museums, -2.4% in smaller museums), between 2009 and 2010 (+6% and +27%), and between 2010 and 2011 (+8% and +13%). And it is not hard to understand why: before the reform, the revenues of the larger museums were equally distributed and were often diverted to the smaller museums, which, thanks to the results of their larger siblings, benefited from a lifeblood for their activities: it was an ideal model for a country like Italy, which has dozens of small museums scattered throughout the territory and, on the contrary, very few centralizing museums. After the reform this was no longer the case, since, with the solidarity fund removed, the autonomous institutes obviously no longer guaranteed these inflows of resources to the smaller museums.

As a result, since the reform, the trend has been reversed, in the sense that the major museums no longer acted as a driving force vis-Ã -vis the smaller museums, and if the big ones took off, the small ones pulled the brakes, so much so that in 2016 visits to the smaller museums even decreased compared to the previous year (average of 48,441 in 2016 compared to 49,098 in 2015): in absolute terms, +7% and +4% in 2014, +7% and +8% in 2015, +6.3% and +0.56% in 2016. So if we have to find a first effect of the reform, it is this: autonomy has guaranteed excellent results for the new thirty “super museums” (in the 2016 “top 30”, there were as many as 19 autonomous institutes), but the ministry seems to have almost forgotten about the smaller museums. And if one compares the average figure with the year of the greatest influx to the smaller museums, 2011, the decline is quite drastic: it went from an average of 51,286 visitors in 2011 to 48,441 in 2016 (a decline of 6 percent), compared with 688,592 in the “top 30” in 2011 and 829,770 in 2016 (an increase of 20 percent). Data that seem to confirm the fear of many insiders: that is, the fact that the ministry focuses almost everything on the big attractors and instead tends to deal much less consistently with the small museums spread throughout the territory, those that may lack the fetish works or the name that appeals to tourists, but are fundamental to a community or an area. Interesting, then, is the figure for the regions affected by the 2016 earthquake: Umbria, Marche and Abruzzo, which experienced declines in overall visitor numbers of 5.32 percent, 4.29 percent and 11.96 percent, respectively. Comparing the data with tourism statistics (we only found data for the first nine months of 2017 for Umbria and Marche), it turns out that tourism actually held: compared to 2016, both arrivals and presences grew in Umbria, by 3.4 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively, while in Marche, arrivals dropped by 4.89 percent, but presences remained essentially stable, marking a decrease of 0.10 percent. Many pointed out that the protection machine in those regions was (and still remains) undersized compared to the needs: the data on flows in museums confirm this.

Returning to the big numbers of 2017, it is necessary to highlight the fact that the results fit into the groove of a trend that goes back as far as 1996, the year from which data on visitor flows in museums managed by the ministry are available. In other words, apart from a few setbacks (the most important were those between 2007 and 2009, in the first years of the great recession, and between 2011 and 2012, the latter, however, motivated above all by the change in the counting system at the Miramare Castle Park in Trieste, following which more than two million visitors were removed from the tally), the number of visitors to Italian museums has been growing both in averages and in absolute terms. Wanting to tie the data to the performance of international tourism, it is easy to see how the growth of visitors to Italian museums follows the continuous growth of tourism (except for the period 2008-2009): according to thelatest report of the UNWTO, the United Nations World Tourism Organization, arrivals in Europe have risen from 303.5 million in 1995 to 616.2 in 2016. Numbers, moreover, are expected to increase considerably in the coming years, according to forecasts: it is therefore fair to expect that the number of visitors to Italian museums will continue to rise in the future. Italy, from 2010 to 2016, experienced an increase of nine million more tourist arrivals: and what do many tourists in Italy do, if not go to visit museums? It should also be considered that in recent years Italian tourism has experienced an increase thanks in part to the negative results of its most direct competitors: between 2015 and 2016, France saw a drop in arrivals of 2.2 percent, and the same is true for Turkey (although the last available survey is that between 2014 and 2015, with a drop of 0.8 percent) and the countries of North Africa (Egypt even marked a -42 percent: in 2016, barely a third of the tourists arriving in the country in 2010 arrived). Other countries such as Greece and Germany, on the other hand, grew, but at a significantly slower pace than in years past. There are not a few analysts who relate these figures, unfortunately, to thepsychological effect provoked by the terrorist attacks-an effect that would seem to have favored Italy. The tourism data show, in short, how the growth of museums follows a trend that, with the Renzi-Franceschini reform, has very little to do: most likely the number of visitors would have grown even with other governments and other ministers.

Let’s move on to analyze the figure on receipts, which, as anticipated, again set a record of more than 193 million euros. The press release did not release data on paying visitors, but merely reported that non-paying visitors experienced a 15 percent growth. Doing some calculations while waiting for the full official data, this means that paying visitors increased by 5 percent. This would be, pending confirmation, the worst figure since 2013 (when the increase was 5 percent, with increases of 8.04 percent, 8.9 percent, and 8.65 percent following in subsequent years), but overall, taking out the years in which paying visitors declined, it is one of the most modest growths since surveys have existed. Conversely, the cost of the average ticket marked the second most conspicuous increase ever: according to partial data, there would have been a +5.23% increase compared to 2016, with the average ticket cost breaking through the 8 euro wall for the first time in 2017 (standing at 8.11 euros), compared to 7.69 in 2016, 7.49 in 2015, 7.11 in 2014, and, going back in time, just 4.64 in 1996. To find a more substantial increase we have to go back to 2002, when the average price went, with an increase of 10.83%, to 5.71 euros, from 5.15 in 2001 (and the reason for such a substantial increase is easy to guess: 2002 was the year of the introduction of the euro).

Finally, it is necessary to add one last consideration about a passage in the video in which Minister Franceschini offers his commentary on the data: specifically, it is the moment when he states that the increase in visitors to museums also meant “a great growth of citizens, of families, of people who went to visit the museum of their city.” To verify the veracity of the minister’s statement, one needs to turn toIstat’s cultural statistics, which are available up to 2016, and they show a trend that proves Dario Franceschini right: Italians who have never set foot in a museum during the year have dropped from 70.2 percent in 2012 to 67 percent in 2016 (although they were 67.8 percent in 2011), while those who have not entered an archaeological site have dropped from 77.1 percent in 2012 to 73.2 percent in 2016 (they were 74.8 percent in 2011). One might think that lowering the percentage (which, with regard to museums, peaked at 71.9 percent in 2013, when the percentage for archaeological sites was still 77 percent) was helped by free Sundays (introduced precisely in 2014), which therefore seem to have had the effect of bringing citizens closer to museums. Of course: the price to pay has been an increase in stress on the part of employees and a fruition that has experienced levels of discomfort often bordering on the sustainable. And speaking of ministry employees: the number has dropped from a total of 21,232 in 2010 (source: 2010 ministry performance report) to just 16,475 in 2016 (source: tender 7002415FA5). Numbers inexorably dropped year after year: a sign that, in order to cope with the increased workload, the ministry probably has to resort to external collaboration contracts, with all that this entails in terms of precarious employment.

What, then, have been the real effects of the Renzi-Franceschini reform? The first: a substantial increase in visitors in the largest and most famous museums, which, however, has been counterbalanced by a drastic decline in smaller museums. The second: the setbacks suffered by museums where protection has demonstrated distressed situations. The third: an actual increase in citizen participation, in reference to which, however, the impact of free Sundays, which in 2017 alone guaranteed an influx of three and a half million visitors to state museums, should be analyzed. On the sidelines, as effects not strictly related to the reform: the highest average ticket cost increase since the introduction of the euro and a heavy drop in MiBACT staffing with consequent job precarization.

In light of all this, what can we hope for in the future, aware of the fact that with the March elections we will see the birth of a new government? In the meantime, protection must return to the center of the ministry’s action, and above all it is necessary to put an end to the illogical dualism that sees protection and enhancement in opposition (two inseparable concepts, or at least they were such before the current reform). The action of the future minister must then return to focus on the smaller museums, which are currently struggling: the reform has given too much weight to autonomous museums, which run the risk of becoming more and more playgrounds for tourists, disconnected from their context and territory. A model that risks, in time, to prove a failure: large museums will be taken increasingly by storm (and already many are struggling to cope with the flows), while many of the small ones will be forced to reduce opening hours, services for the public, and research activities, until, probably, they will have to close. But there is always time to reverse the trend. Participation, then, will have to disregard initiatives that extend freebies indiscriminately: an initiative like Free Sundays makes no sense except to grow numbers. Better to incentivize participation with initiatives that truly bring Italian museums closer to European standards, in order to put in place the real revolution we have long been calling for: free for those without employment, stable evening openings, reductions for those who enter the museum in the last hours of opening, extension of ticket validity (especially if the museum is large), agreements with other institutions. And above all, it is urgent to stabilize the work and reinvigorate the ministry’s staff with new and motivated forces that can cope with the needs of a machine that cannot and must not just grind out numbers: it must also know how to transform them into work, actions for preservation, civic sense, community building, participation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.