The invitation to intervene in the discussion rekindled by the improper Ministerial Decree 161 proposes some questions, to which it is not easy to give answers in a few pages. Unless we take note that there are problems made unnecessarily complex by old rules, oblivious to the digital revolution and planetary communication, for which it is perhaps better to find simple solutions. And nothing is simpler than freedom, if that freedom does not infringe on the rights of others. And in fact, one of the knots of the matter is whether the Public Administration has the right to derive economic benefits not from the use of goods and spaces that it has in consignment (this is unquestionable), but from their images, that is, from intangible goods, which we would better define as common goods, the use of which is to all intents and purposes non-rivalrous.

It is not disputed that the collection of these blessed fees produces for the Administration a fiscal damage (the Court of Auditors has also noted this). But the State has no (material) interest to claim, simply because it is not the owner of the intangible asset that are images, and if anything, it has, on the contrary, the obligation of their dissemination under Article 9 of the Constitution. Not least because the text of Article 108 of the Urbani Code (which is the reference norm for the imposition of royalties) should be read in light of the subsequent Faro Convention (now a state law), which states that “everyone, alone or collectively, has the right to benefit from the cultural heritage and to contribute to its enrichment.”

The apparent radicalism of my statement is fueled by the ignoble (I can find no other adjective) reference to Article 20 of the same Code (which protects cultural property in its materiality) by which one would like to justify a preventive control of social behavior, that is, censorship. This perspective is so subversive that it compels us to recall the primary values of the Constitution, even in the wake of the pronouncements of some civil court, which has introduced an unintended right to the image that would be enjoyed by the good itself, as if it were a physical person, in the name of an undetermined Italic genius. Judgments, moreover, stigmatized by the most modern and alert legal doctrine.

To the question of whether the current discipline of reproduction fees risks harming the knowledge of heritage, the answer is therefore certainly yes. While the opposite is not true, since the free circulation of images can do no harm to the physical integrity of the depicted asset.

And so to the question, whether in the age of the web and social media laws can keep up with custom, the answer is no; but laws can and must be changed. That is why we ask Italian legal culture not only to describe the current legal framework to us, almost to cast it, but to foreshadow the future, which is the driving function of law in modern societies.

The presumption that a free use of heritage images (regardless of the monetary aspects, which result in an odious tax on inspiration) can have a detrimental character to their value is another lunar aspect of the current debate. The free expression of thought, safeguarded by Article 21 of the Constitution (when it does not contemplate offense to religious sentiment or the common sense of decency), cannot be conculcated in the name of a smoky defense of the symbolic value of images. Article 21 protects good and cultured beautiful thought, but also ugly, stupid and vulgar thought. To resolve distortions it tries, if anything, social negotiation in the forms in which civil confrontation manifests itself in the public and private spheres ... certainly not the law, least of all when placed in the hands of no one knows to whom, on the basis of what objective or shared principles, with what legal certainty. Indeed, the idea is spreading that public offices, before granting the use of an image, must know, for example, the text of the book for which they are intended. To these intoxications of an authoritarian state it is necessary to calmly reply that the imprimatur imposed for centuries by the Church on publications was abolished with the birth of the Italian state.

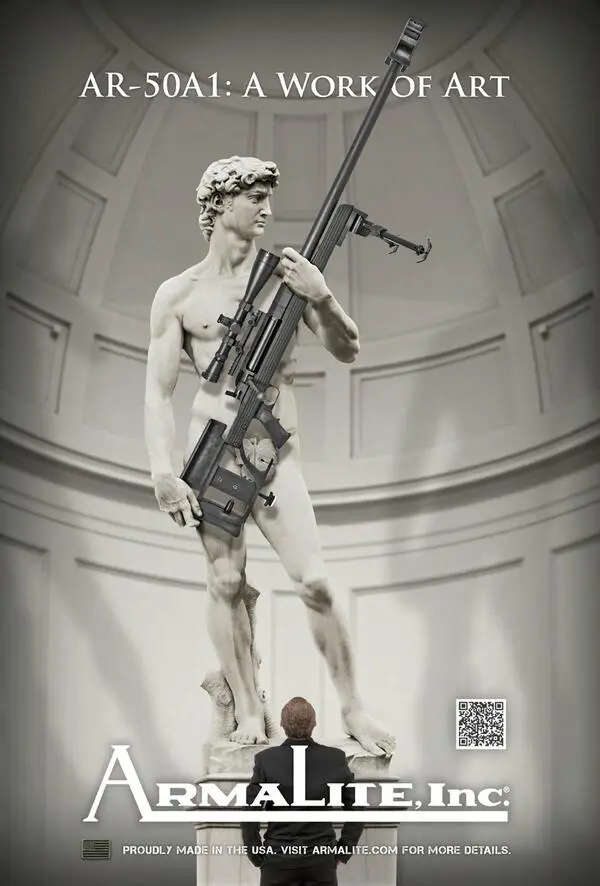

It is necessary, therefore, to ask oneself by what principles one will assess whether the use of the image debases or alters the intangible integrity of the property. Well, I, an elderly archaeologist who is instinctively pacifist, am not at all offended by the advertising image proposed by a weapons company, which depicts Michelangelo’s David with a machine gun in his hand. Am I the unwitting representative of a degenerate sector of Italian society? Or should we say that that image would have been acceptable if David had been holding a carnation, as he did at the time of Portugal’s revolution? Rather, it seems to me that that military reference is simply meant to capture the pose of Michelangelo’s David in the act of preparing the slingshot with which he will kill Goliath: one would say an educated reference by an advertiser who has produced something perhaps distasteful to our sensibilities, but certainly not illegal, since the production and sale of weapons is, alas, provided for in our legal systems. So let us talk about sensibility and/or expediency. What do the courts have to do with this?

The same goes for the image of the David reproduced in a fashion magazine alternated through a morphing effect with the image of one of the most famous Italian models in the world. Everyone can freely judge the good or bad taste, but no one will escape the fact that the morphing technology merely adapts to the times what Eugène Bataille did 150 years ago, with his famous Mona Lisa smoking a pipe (horror!), and then in 1919 Marcel Duchamp by applying a mustache to the image of the Mona Lisa along with a very vulgar caption. Is it (was it) art? meaningless question, since, God willing, there is no public definition of what art actually is, so much as to shelter it from the screeches of old and new inquisitors. Moreover, the use of cultural heritage images for “free expression of thought” is already enshrined in Paragraph 3a of Article 108, recently amended, which thus prevents the use of Article 20 of that Code to prohibit that very freedom. How can one cry scandal if, in Florence, a photograph of the facade of the Baptistery appears in the company of a few bottles of limoncello? are we not talking about a pride of Made in Italy? or is the production of alcohol forbidden by Italian laws? “But you can’t associate art with alcohol!?” Yeah, tell that to the endless artistic depictions of the Last Supper! Or let’s throw the canvases of Jackson Pollock, who struggled all his life with alcoholism, to the bucket.

To entrust the preventive censorship of social behavior to an administrative office is therefore to burden the administration with tasks completely foreign to its nature, which would only widen the already frightening gap that current regulations have produced between administration and civil society. And if, according to some judges, we should consider any critical appreciation of our artistic heritage unlawful, know that-if we don’t wake up! - we may express polite doubts about the virginity of the Madonna, but we could not say in public "How ugly is the David!“, ”Botticelli/Santanché’s Venus looks like a shaman!“, ”the Colosseum looks like a half-false carious tooth!", as Cederna quietly wrote about the Mausoleum of Augustus.

It is time for the art world to strike a blow, too. And that we finally take note that if images are the immaterial projection of a material good that is properly protected in its physicality, a problem of protecting cultural heritage images instead simply does not exist: it is the concept itself that does not work. It is something reminiscent of the indissolubility of marriage or the murderous defense of marital honor: obstructions provided for by law and luminously tossed aside by a grown society.

This contribution was originally published in No. 20 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.