Documenta 15 and the Historikerstreit 2.0. Chronicle of a diatribe announced

For those unfamiliar with it, Kassel is a German city in the heart of Hesse, difficult to reach by public transportation, and where rarely anything interesting happens. Even tourist facilities are almost absent: hotels, public baths, restaurants can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Every five years, however, for one hundred days, Kassel becomes the beating heart of international contemporary art. Documenta, now in its 15th year, is surely, along with the Venice Biennale, one of the most important contemporary art exhibitions taking place in Europe.

The German exhibition was created in 1955 at the behest of Arnold Bode (1900-1977), a professor of painting at the Kassel Academy. The choice to exhibit in this city was not accidental: the Friedrichplatz is home to the Fridericianum, a building founded in 1779 with strong political and cultural connotations. In addition to being one of the world’s first public museums, the structure was a “Ständepalast,” housing the German parliamentary chamber from 1810 to 1813. In 1955, the goal of the exhibition was not only to provide a survey, a “documenta ”tion, of postwar German art; in fact, the exhibition came into being primarily to “wash away” the image of Nazi and anti-Semitic Germany that, in the field of art, had manifested itself in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition of 1937. Bode’s project was immediately met with total acceptance. Over the years the exhibition has grown a great deal and, unlike the more institutionalized Venice Biennale, the political, economic and social aspect has always been at the center of the artistic debate.

The current documenta is no different: the political debate in which it is involved even before its inauguration is in the German news more than the works exhibited in it. The peculiarity and controversy that would trigger this documenta15 was in the air as early as the summer of 2019. The then art direction committee, whose members included Frances Morris, director of the Tate in London, and Charles Esche, director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, came out in favor of the Indonesian art collective Ruangrupa. From the outset Ruangrupa did not seem to be particularly interested in the logic of the contemporary art market: as the art project and the names of the artists involved were made public, a clear curatorial line became increasingly evident. There was a shortage of galleries and contemporary art “biggies” and, therefore, the absence of any financial speculation for a project more focused on the community and the solidarity maintenance of the art ecosystem, according to the guidelines of a real sharing economy. From the very beginning, Ruangrupa intended sustainable management and resource sharing to be a central aspect of the exhibition, without the pretension of abolishing capitalism, but with the desire to experiment with small acts of solidarity. Indeed, this documenta envisions the involvement (artistic, but also economic) of collectives and activists from regions defined in cultural studies as “Global South,” those hitherto less represented in the Western art system. The imminent consequence of the intervention of fifty-four collectives for nearly one thousand five hundred artists from the Global South is a careful reflection on the issues inherent in postcolonialism, along with the deconstruction of what Edward Said had called “Orientalism.” The choice of appointing the Jakarta-based collective for the artistic direction of this event is to be considered a first in the history of documenta. Little understandable, on the other hand, is the choice that fell precisely on Ruangrupa whose “subversive” intentions with respect to a curatorship to which we Westerners are accustomed were known to the committee. One can speculate that this choice somehow reflects the interests and debate of several museums in Europe engaged in the return of pieces stolen in the colonial era and in reflecting on how museum collections of the future can and should tell a “different story.”

Surely neither Sabine Schormann, director general of documenta, nor Claudia Roth, Minister of Culture and Media in the Scholz government, nor the Ruangrupa collective itself would have ever imagined that documenta15 would become the scene of one of Germany’s most important cultural-political querelles since the beginning of the new century, so much so that in recent days some of the more extremist wings have called for the event to be shut down. The subject of the querelle? The accusation of anti-Semitism against the artistic direction and some of the collectives invited to exhibit. In a country that is still struggling to come to terms with its past, which has tried to forget it rather than face it critically, anti-Semitism is an issue that reopens a Pandora’s box that for decades has been tried to keep if not closed at least half-closed. In the months leading up to the Kassel event, there were a series of unfounded and deeply cynical attacks on the exhibition, its curators and many of its artists. The accusations were initially made by Josef Schuster, president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, who, on his forum, had faulted Ruangrupa for inviting collectives close to the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Movement (BDS), particularly The Question of Funding, and for excluding Israeli artists from participating in the Kassel art exhibition.

The claims immediately found fertile ground in some right-wing German parties, such as the Antideutsche and AfD, and were reported uncritically by parts of the German press. In a Jan. 17, 2022 article, WDR reported, “An alliance has accused the Indonesian artist collective Ruangrupa of including organizations that support the cultural boycott of Israel or are anti-Semitic in the upcoming documenta. Among others, the accusation is aimed at a Palestinian group that allegedly advocates boycotting Israel in cultural life.” In a May 1 article, the Welt newspaper asked why the accusation of promoting anti-Semitic or anti-Israel positions was not belied by the facts and lamented, on the contrary, how the criticism was countered with an egalitarian response that documenta did not want to give “a platform” to “generic statements about people of Muslim or other backgrounds.” Right up to the headlines of recent days, in which again the same newspaper denounces anti-Semitism as a practice inherent in this exhibition, “Antisemitismus als System - das documenta Protokoll.” The outcomes of this initial smear campaign led to real attacks on the collectives involved: a few weeks before the opening of the exhibition, the exhibition space of the Palestinian collective The Question of Funding a documenta15 was vandalized. The codes “187” (used in the U.S. as a death threat) and “Peralta” (the name of Spanish fascist politician Isabelle Peralta) stood out on the walls of the exhibition. On a sticker used for a demonstration in Berlin against anti-Semitism, promoted by unknown persons and organized for May 15 but never fortunately realized, one could read the phrase “Wir suchen den Antisemiten des Jahres! Und shicken ihn mit seinesgleichen in die Wüste” (“We seek the anti-Semite of the year! And we send him with his kind into the wilderness!”) flanked by a number of symbols, including those of Amnesty International and BDS, against the backdrop of a dog’s butt.

These are grotesque episodes that, as Berlin-based South African artist Candice Breitz has well pointed out, must be understood as ongoing and deeply aggressive attempts by the right wing to de-pluralize cultural and public discourse in Germany; to defund progressive art and culture to silence the voices of Muslims, Palestinians, non-Westerners, people of color and Jewish leftists; and to delegitimize de-colonial activism in a nation that has just begun to confront and acknowledge its violent colonial past. A nation that can barely spell “Namibia” and still prefers to pretend it was responsible for a single historical genocide.

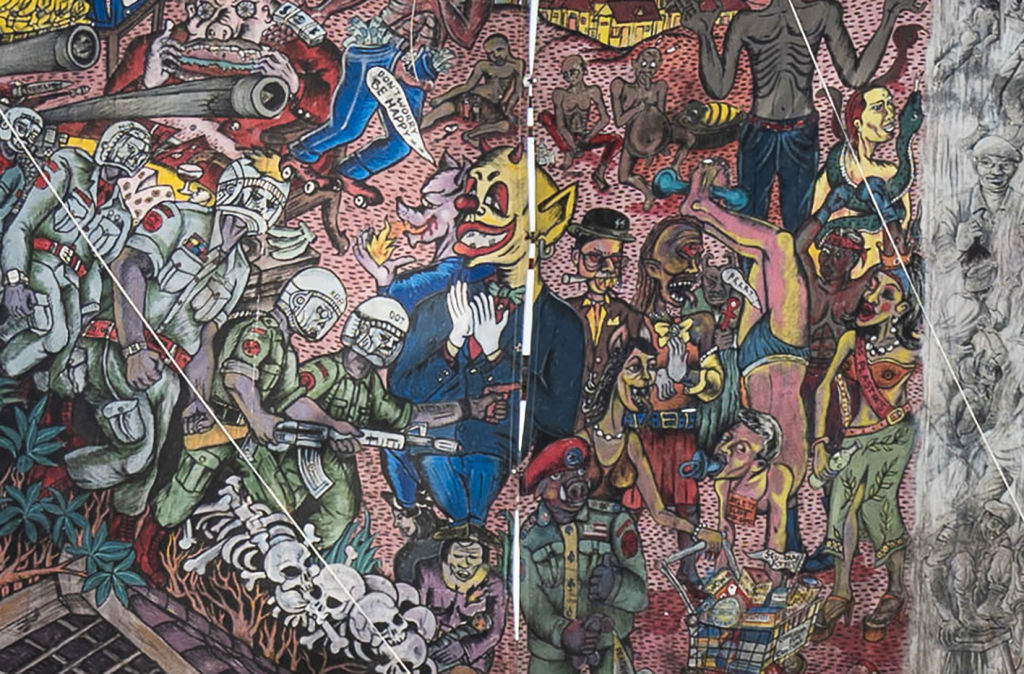

Accusations of anti-Semitism became insistent as soon as the exhibition opened its doors. The banner of Taring Padi’s People’s Justice installation, located in front of the entrance to the documenta Halle, features distinctly anti-Semitic symbolism. The work was created in Ýogykarta in 2002 by Taring Padi, a collective of artists and activists in the Indonesian city that was formed in 1998 following the mass uprisings (suppressed with blood) resulting from the economic crisis. People’s of Justice, exhibited for the first time in the West, is set against the backdrop of the 1998 student protests that led to the end of the dictatorial Suharto regime (1965-1998). The main theme of the work is the contrast between the capitalist-military power complex and the oppressed people. Above the oppression scenario is a kind of purgatory in which the oppressed (the people) judge the oppressors (the Suharto regime, its collaborators, the police, and its Western supporters). Several contemporary studies (the first by Butwell in 1979) have shown that Suharto’s strongly anti-communist and repressive dictatorial regime was consciously accepted by numerous Western governments and institutions, including the United States, the CIA, the International Monetary Fund, the Bundesnachrichtendienst and Mossad. Precisely to represent the latter, Taring Padi made use of well-known symbolism within the Indonesian political context: soldiers and soldiers symbolized by pigs, dogs, and rats, as a critique of the capitalist system and military violence. Two of these figures have been accused of having offensive content toward the Jewish community: among the characters representing oppression are a glimpse of an Orthodox Jew with vampire teeth and SS runes and a pig-faced soldier wearing a helmet that reads “Mossad.”

Taring

Taring Taring

TaringAs early as the Monday following the opening weekend, the banner was obscured, and after a few days the installation at Friedrichplatz was completely removed. Press releases of official apologies from Ruangrupa, Taring Padi and documenta’s general director, Sabine Schormann, were of little use. The accusations soon turned into a full-blown stoning conducted by various parties: Meron Mendel, director of the Anne Frank Education Center, by Claudia Roth, by Boris Rhein, president of Hesse, and by various parties such as AfD, CDU/CSU who last July 7 filed a motion to provide “appropriate responses to the scandal of anti-Semitism at Documenta.” Also unheeded remain the words of almost the entire German art community, especially the Berlin art community, which has since the beginning declared its sympathy to the artistic direction of Kassel, in the name of a deeper reading and contextualization of the work in the hope that a mistake will not erase the work of years and the works of the more than 1,500 exhibiting artists. The general director, Sabine Schonmann, the mayor of Kassel, Christian Geselle (SPD), as well as the Ruangrupa collective itself, were asked not only for more control over the exhibited works, but also for the closure of the event itself. Certainly unexpected was the reaction of artist Hito Steyerl, who decided to withdraw his video installation, Animal Spirits, exhibited at the Ottoneum. The reasons concern the repeated refusal of a sustainable and structurally anchored dialogue around the exhibition, as well as the refusal of the art direction to accept any mediation.

Predictable, but not desirable, was the resignation a few days later of Sabine Schornmann, who was the sole scapegoat in the whole affair. Schornmann has not only always defended Ruangrupa, but has consistently rejected accusations of inaction and lack of dialogue on the part of the collective. However, the reactions and responses by both accusers and those accused of anti-Semitism run the risk of falling into oversimplification: both in Taring Padi’s relativism in claiming to have referred exclusively to the historical context of Indonesia without thinking of the consequences such images would have in the West; and in the monocausal connection made by critics, i.e., Muslim country equals anti-Semitism. Certainly it is true that in the course of its twenty years of existence, the work has been exhibited elsewhere (Indonesia, China, Australia) without receiving any comment on it. To turn, however, anti-Semitism into a problem of who perceives it, specifically the subjective reception that has been observed in Germany, implies a non-recognition of the work and its contexts. All the more so when this occurs at the hands of a collective from Indonesia, a country that recognizes neither the Jewish religion nor Israel. These are blatantly anti-Jewish image patterns (the vampire Jew and the pig Jew) established at least since the late 19th century. People’s Justice is certainly a product of Indonesia’s context of oppression twenty years ago, but those in charge of the curatorship should have paid more attention to the German exhibition context, especially following the initial accusations of anti-Semitism. Ruangrupa would sooner or later have had to come to terms with a country where the uniqueness of the Shoah and the competition of memory between the Holocaust and colonialism do not allow for a debate that goes beyond mere accusations of anti-Semitism. Enzo Traverso discussed this at great length in a recent article in Jacobin that examined precisely the Historikerstreit 2.0, born out of the events in Kassel. The scholar makes clear the importance of reconsideration and consciousness, even for Germans, of the genocides perpetrated during colonialism. Indeed, the feeling that comes from this what seems to be a German querelle, which for the time being is struggling to see an end, is precisely that it is the continuing tension between anti-Semitism and postcolonialism in a context poised between the perspectives of the Global South and German historical responsibility.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.