Davide Gasparotto: Bringing those who want to see Antonello da Messina's Ecce Homo to Piacenza.

After the article on Sgarbi’s exhibition at the Eataly Pavilion for Expo 2015, written by our Federico and published last April 22 in Finestre sull’Arte, we were contacted by art historian Davide Gasparotto, current Senior Curator of Paintings at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and former official of the Superintendence of Artistic Heritage of Parma and Piacenza, responsible for Piacenza. He sent us a contribution of his that appeared last Saturday, March 21, in the Piacenza daily Libertà : Davide Gasparotto is one of the few voices raised against Sgarbi’s exhibition, in this case to prevent Antonello da Messina’s Ecce Homo, preserved in Piacenza, from taking the road to Milan. A few voices, but strong and passionate: it is for this reason, as well as for the commonality of views, that we intend to amplify the competent and very interesting voice of Davide Gasparotto through our website by offering you the contribution that came out in Libertà . Happy reading!

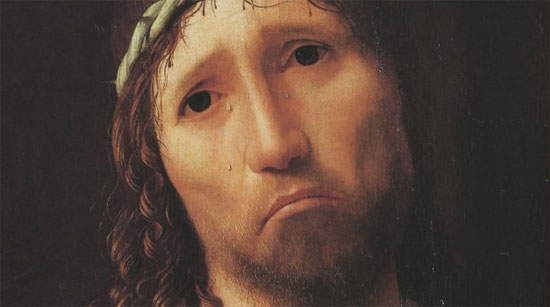

Starting from the case of Antonello da Messina’s masterpiece kept at the Alberoni College in Piacenza and the recent controversy raised about its denied loan for an exhibition, I would like to try to reason for a moment about what are the purposes and what does it mean to loan a work of art to an exhibition.

Indeed, lending a work of very high value (not just commercial value) entails important responsibilities for those who own or care for it. Before granting a loan, the questions one must ask oneself are basically threefold:

- Is such an important and delicate work able to travel without risk?

- What, if any, conditions of transportation and set-up are guaranteed by the applicant?

- What is the cultural and scientific motivation for moving a masterpiece that, although able to travel, is still an extremely fragile creature?

These are all questions that the president and administrators of the Opera Pia Alberoni have asked themselves and answered with great foresight and sense of responsibility. To the first they answered with a possible “yes,” but to the other two the conclusion was negative. In reading the “Facility Report” of the proposed venue for the exhibition (i.e., that document certifying the exhibition conditions guaranteed by the organizers) the conditions for a safe display of Antonello’s masterpiece also did not exist in my judgment.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo (c. 1473-76; Piacenza, Collegio Alberoni) |

With relative humidity at 40-45% (so in the document exhibited by the organizers) no foreign museum would ever have loaned a panel as thin and delicate as the Alberoni Ecce Homo. If we then move on from the guarantees offered by the organizers to consider the scientific project of the exhibition, frankly the sense and necessity of the presence of Antonello’s painting in a list that appears as all-encompassing as it is heterogeneous escapes us. The only glue of the works on display seems to be that - rather generic - of being products of excellence of that “Made in Italy” that the Eataly Pavilion proposes to celebrate, within a context that inevitably shifts its value from the cultural to the commercial level. An exhibition, then, that is unable to shine any new light on Piacenza’s masterpiece. Why risk it, then?

I have read that the painting’s presence in Milan would work as a tourism attractor to the ill-known and neglected Piacenza. But the belief that the relocation of a masterpiece can have a positive impact on cultural tourism in any city of art is completely erroneous. If anything, the opposite is true; it is the loan of the prestigious work that ennobles the exhibition. It is certainly not by sending Antonello to Milan and Botticelli to Japan that one promotes awareness of the local artistic heritage. Instead, it is by investing in resources to promote it “in situ” that lasting results could be achieved.

However, it cannot be claimed, as has also been done, that Piacenza’s Ecce Homo is little known. The painting is among Antonello’s most famous, and the Opera Pia Alberoni over the past fifteen years has carefully enhanced it through a new display (an air-conditioned vitrine that allows its temperature and humidity conditions to be constantly monitored) and also by exceptionally lending it to initiatives of relevant cultural interest, such as the comparison with the Ecce Homo preserved in the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola in Genoa (2000) and the major monographic exhibition on the artist held in 2006 at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome, where Antonello’s masterpiece was flanked by versions of the same subject now at the Metropolitan in New York and the Louvre in Paris. In recent years, then, the Opera Pia undertook, entirely with its own funds, a complex and costly project to retrofit and renovate the layout of the so-called Alberoni Gallery designed by Vittorio Gandolfi in the 1960s.

During the long years in which I was an official of the Superintendence of Parma, collaboration with the Piacenza institution was always very intense and cordial, giving me the opportunity to appreciate the great care taken by the administrators to protect and make the most of the conspicuous artistic heritage housed in the College.

Antonello’s Ecce Homo is the very symbol and heart of the Alberonian collections, and I well understand the caution and reluctance of the administrators to let it travel without more than a cogent reason. These are sentiments that do them credit.

The icon of the Getty Museum where I have been working for the past few months is Vincent Van Gogh’s famous iris painting. As I learned shortly after my arrival here, it never leaves the museum for any reason. Those who come to Los Angeles want to find it there. So let us try to bring those who want to see Antonello to Piacenza.

Davide Gasparotto

|

| Vittorio Sgarbi, photo by Perugia Online released under a Creative Commons license. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.