Cultural decolonization: is it right to return artworks from our museums to their countries of origin? Part two

This article represents the second part of the discussion on cultural decolonization that we hosted in our magazine. To read the first part you can click on this link.

|

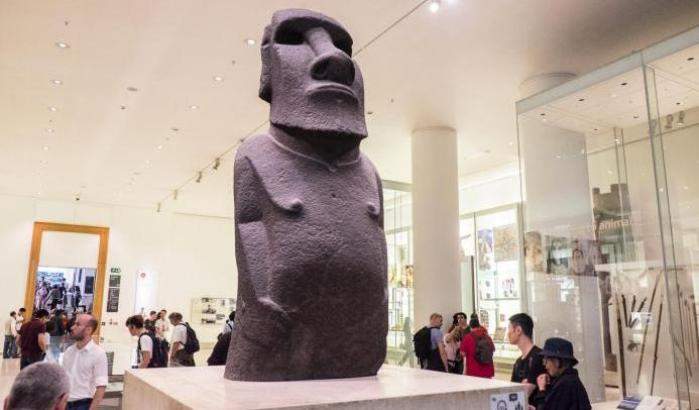

| The British Museum’s moaï at the center of a heated debate over its return to the island of Rapa Nui |

Beatrice Nicolini

Associate Professor of African History and Institutions, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart

Regarding the works of art and, more generally, the objects that have been stolen and requisitioned in Italy by other countries in the history of the entire nation, I do not think it is possible to imagine a collective restitution of a quantity of works that is very large in terms of numbers and also as complexity: I think it would be a titanic operation, unmanageable and unattainable, by any nation, moreover, Italy has such a great monumental and artistic wealth that we cannot even show everything we have. Therefore, I would not be in favor of the nationalistic idea of returning the ill-gotten gains, the spoils of war: I find it to be a decidedly anachronistic thing.

Instead, the reverse operation is a very political discourse, and I also believe that we need to distinguish artworks from objects of material culture. Let me give an example: at the end of the 19th century, the chief of the Herero, a tribe in Namibia, was killed by the Germans, and to demonstrate the latter’s great military efficiency, the chief’s head was sent to Berlin (this was, moreover, something that General Rodolfo Graziani, an Italian, also did, sending Rome heads inside Lazzaroni cookie tins). This testimony of pure horror, the head of the Herero chief, was returned in 1958, meaning it remained in Berlin for almost a century. These kinds of operations, which of course do not have to do with works of art, but do have to do with the humiliation of populations and the absolute brutality they suffered, certainly require a complex and articulated path that starts with an official apology from one country to another: these, in some cases, should also perhaps be followed by restitution, as we did, for example, in the case of the Axum stele that left Rome for the Horn of Africa.

Ultimately, I think that for Italy this is a need without content and without purpose. Conversely, it is a very political operation that must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis: the role of the former colonial powers carries with it a very heavy inheritance that then implies other situations. I’m thinking, for example, of the case of the reparations movement, which is very strong especially in African-American communities, which argues that nations that have enriched themselves through the diversion of resources, whether artistic or natural or human, from others, are owed restitution. And these are not necessarily repayments of objects, but also consideration indicated in money.

Maria Stella Rognoni

Associate Professor of African History and Institutions, University of Florence

In Italy, which was also a colonial power in Africa between the end of the nineteenth century and 1960 (the year of the end of the Trusteeship in Somalia) that of decolonization has never become a topic of public discussion, as it happened and happens in France or Great Britain. Only today, against the backdrop of the great theme of migration, a part of the Italian public opinion finally feels called upon and would like to have tools for understanding a past that has never really been addressed and is often repressed.

The question of the fate of African works of art preserved in European and American museums can represent, from this point of view, an opportunity, especially if it can be turned into an opportunity for dialogue with African counterparts, not only governmental ones. Giving a voice to those who have been deprived of their history, including through the subtraction of artworks, is the first step in changing perspective. So let’s hear from art experts in Benin or Cameroon, school teachers in Addis Ababa or Kampala: how much importance do they attach to possible restitution? What processes of renewal and knowledge could activate thoughtful and shared restitutions, or, on the contrary, concerted choices aimed at preservation of works in European museums? Unilateral decisions by any ex-colonial government, perhaps taken for contingent objectives, or even agreements between governments, as happened and with much difficulty in the case of the Axum stele between Rome and Addis Ababa, in fact resolve only part of the question, and perhaps not the most relevant.

At stake instead is the possibility of offering (in Europe, as in Africa) spaces to discuss a shared past that has transformed both those who suffered colonization and those who imposed it, and to reflect on the present that is the fruit of those experiences. On the other hand, there are already a great many African museum projects that put this kind of reflection at the center of their activities, but very little is known about this in Europe and Italy.

Ilaria Sgarbozza

Art History Officer, Parco Archeologico dellAppia Antica, Rome

Research, confrontation, collaboration. On these three paths Italian and foreign cultural institutions should seriously begin to move. Historical research to bring out political and collecting events of the modern and contemporary ages, only partly known. Comparison among scholars of different affiliations to establish common (or at least compatible) keys to interpretation of historical events. Collaboration among institutes (museums first and foremost) to develop international projects (exhibitions, dissemination and in-depth days, special initiatives), on the theme of cultural decolonization. The material and permanent return of works may not be the only solution. Temporary loans, publications, public meetings, could take shape as a viable alternative.

Pieces of Italy, the result of spoliation in some cases violent, are everywhere in the world; housed in museums or historical palaces, they are not infrequently displayed with refinement and appropriateness, enhanced and communicated to a wide and varied audience of visitors. How much has this contributed to the international primacy of our culture, particularly Greco-Roman classicism and its exceptional derivations? Let us try to question this as well.

Giuliana Tomasella

Full Professor of Museology and Art Criticism and Restoration, University of Padua

The topic of restitutions is at the center of scholarly interest and much debated in museum circles. However, I have the limpression that our country is not yet ready to enter the debate, due to the process of removal from collective memory concerning our colonial past. Although there have been important historical studies in recent decades that have shed full light on the events related to Italian colonization in Africa between the 1880s and the end of World War II, very little has passed at the level of public consciousness. Not even the resounding return of the Axum obelisk (which also filled the headlines for a few days) seems to have left a lasting impression. This is why I believe that the establishment of an ad hoc committee would be most appropriate, while being aware of the complexity and delicacy of the issue.

Indeed, it would be necessary to clarify, on a case-by-case basis, the circumstances under which the artifacts arrived in our museums and to act, hopefully, within a framework of international consultation. I believe that the broadening of the debate could/should be the occasion, first of all, for a critical rethinking of the ways in which artifacts from our former colonies are displayed, providing museum visitors (especially the younger ones) with suitable tools to acquire a full awareness of all that they imply. That is, they should be taught to see, in addition to the objects themselves, the web of their connections, the unfolding of their history, past and recent, shedding light on the journey that led them to us. And also to teach us to reflect on their status: in many cases, in fact, the Italian public is still influenced by a strongly ethnicized art history, which for a long time has denied works made by African artists the very definition of art, relegating them (for example in colonial exhibitions) to separate sections devoted to handicrafts or ethnography.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel

Director of the Paestum Archaeological Park.

The question of so-called decolonization, or post-colonialism, regarding collections from other continents is already extremely complex, but the question ofItaly is even more complex: there have been conquests and forms of spoliation and looting, an activity that has led to a flow of antiquities fromItaly to other countries. However, Italy also represents that classical culture whose testimonies are not considered as those that belong, for example, to Indian culture, or Central African, or Mexican culture: instead, it is, for Europe, a heritage that in a certain sense is common. So we are talking about different subjects. The red-figure vase that is in London is different from the ritual object stolen in South America: if the latter can be associated with a discourse typical of a relationship between colonizers and colonized (in the sense that such an object was seen as an exotic thing, but also as the appropriation, by the colony, of a culture considered inferior: this was the attitude of the colonizers), in the case of classical culture it can be said that the vase is in a foreign museum because those who took it away from Italy or Greece in the past saw it as an element of an original root of our European culture.

This further complicates the issue: on the one hand, countries like Italy, Greece and Turkey can rightly be proud of a heritage that is recognized by many other countries globally, while on the other hand this obviously implies a great deal of interest on the level of the antiquities market as well, in the sense that in Italy we are happy with the fact that everyone is looking at Italian history, allarcheology, culture, but the other side of the coin is that everyone wants to have a piece of this history, of this culture. And claiming the centrality of classical culture can almost become a justification for this kind of attitude. I am thinking especially of Greece or Turkey: there are museums or collectors who claim that only through their intervention have ancient works survived (I am thinking, for example, of the Pergamon altar). In short, it is an extremely complex topic, because the discussion about restitutions is not only about the issue of colonialism and exoticism, but also about the issue of heritage understood as a common origin and as the cradle of culture.

Finally, there is also another consideration to be made: there are cases where Italian or Greek objects entered historical collections centuries ago, but there are also cases where we have very strong doubts. For example, there is a clearly Pestan tomb on display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York that entered the collection in recent years, about which we never knew anything about its provenance. In addition, clandestine excavations in Italy continue, and so doubts remain about the legitimacy of the belonging of certain objects to certain collections.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.