Crashed and happy. From Barbie to Helmut Newton, via Sandro Giordano.

Art represents us or, put another way, we choose the art that represents us most. And it is not just an incipit in line with a historic campaign of the Ministry of Culture that said #lartetisomiglia, but it is more simply the evolution of that instinct of self-preservation that led our ancestors to paint on cave walls to leave a trace of their passage in the world and on which (from there on) art as we tell it today was born.

In short, while we strive to know art, the one officially defined by someone, and to admire it in museums in a more or less convinced way, then, in the secrecy of our likes, we choose by instinct and lightly the representations in which we find a resemblance to the image we have of ourselves. It could be a social attitude that leads us to group and homologize, or it could be the merit of mirror neurons, which physiologically explain our ability to recognize ourselves in our fellow human beings, and feel empathy even when they represent their imperfect everyday life.

It is to this that I attribute the success of Remmidemmi, born Sandro Giordano, a self-taught photographer with a gallery of 200,000 followers on Instagram and an exhibition now underway at Rome’s Strati d’Arte gallery curated by Gina Ingrassia entitled In Extremis (bodies with no regret). His portraits, patiently constructed in sets, tell the story of the moment after a fall, surreal, decomposed, deflagrating. A project that for ten years has been repeated according to a strandardized yet each time surprising format.

Sandro Giordano

Sandro Giordano Sandro Giordano,

Sandro Giordano,In an interview some time ago he recounted, “It was September 2013, I was taking part in a show and on stage there was a very imposing staircase. One of the actresses, as we were passing the time before rehearsal, asked me to take a comic picture of her, and right away I visualized her image at the bottom of the stairs, fallen, with her face turned to the floor; she put herself in that position and there I glimpsed something, an intuition. On Oct. 12, once I got back to Barcelona-where I was living at the time-I woke up in the morning, opened my eyes and thought ’I have to do this.’ ”

The protagonists in his images are crashed to the ground, with the full load of their belongings, out of a bag, dropped from the car, rolled down the stairs. They are frozen instants of a story that we can walk backwards through by imagining not only the fall, but the life that came before: work, a hobby, a fun evening, the beginning of a journey. For the fall is a sudden event in the middle of a journey.

Giordano’s falls are disjointed, unreal, exaggerated, never tragic. They are images charged with an irony underscored by outsized objects and bright colors. It almost seems as if the “fallen” is becoming aware of what has happened, regaining his strength, and - why not? - enjoying a moment of respite before getting back up.

Yet, the subjects never show their faces. Because, after all, there is a thread of modesty in those who tell them, but also because - in my opinion - this choice suggests that that crash is often not real but is a feeling we carry within us, whether it is a pain ready to deflagrate, or it is just the awareness of being confused and imperfect. In the space of the exhibition, it is apparent that the subjects portrayed are mostly women. It may be that we are more complicated, multi-faceted, or more simply so addicted to doing several things at once, that we are more distracted, used to falling down and getting back up.

"More than sunsets, more than the flight of a bird, the absolute wonderful thing is a woman in rebirth. When she gets back on her feet after the catastrophe, after the fall.

That one says: it’s over.“ said Jack Folla the character written by Diego Cugia for the Radio 2 show, ”Alcatraz," now twenty years ago.

And if this is not just another promotion leveraging women, when I go to choose among the cultural offerings these days in Rome I realize that everything is tinged with pink. In a context where everything is feminism, art - in the broadest sense - is also moving in the wake. And so the woman is now at the center of every narrative, an involuntary presence at every event.

Still in the movies is “Barbie,” which tells the stereotypes of today’s feminism: accomplished, beautiful women, managers, presidents, astronauts, or mothers who can traverse parallel worlds to save their families but feel the weight of expectations that are never fully met. “It is literally impossible to be a woman. You’re so beautiful and so smart and it kills you that you don’t think you’re good enough. We always have to be extraordinary, but somehow, we always do it wrong,” says America Ferrera in a monologue that winks at the Oscars. A film that has lent itself to many different interpretations, down to Boris Jonson’s subtly conspiratorial one in the Daily Mail last July 23 “What is the message of the film? What does Mattel want? ... It wants more babies who will soon become children who demand dolls. Mattel wants humans to reproduce.”

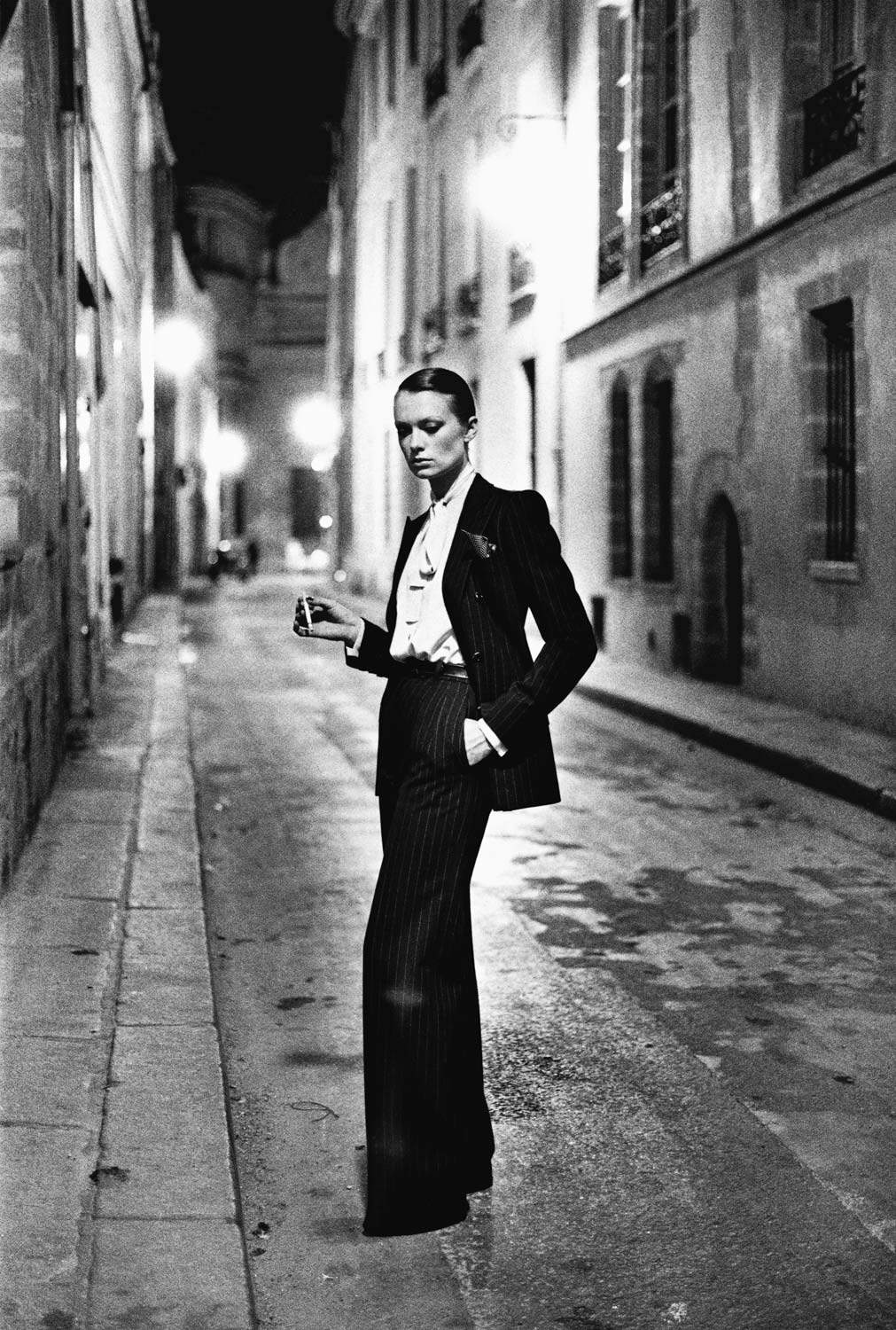

But Helmut Newton is also sold as a feminist, and his exhibition “Legacy” at the Ara Pacis in Rome until March 10, 2023 speaks of independent, empowered, resolute, seductive women in a black and white that emphasizes the perfection of every curve, and zeroes in on every flaw. These are women who conquer, who dominate, who attract, and they are so depending on who is looking at them, whether a character in the picture or the viewer’s gaze.

A rich, enveloping exhibition with its large, poster-sized prints that I recommend to every lover of photography, but also to every lover of beauty.

In short, women, if we have not achieved equal pay (as whoever mentioned the Nobel Prize awarded to economist Claudia Goldin reminded us), at least we can enjoy the freedom to choose, among the infinity of artistic expressions tell us, which one represents us most.

I chose, and in a set set up for the public I could not help but offer myself as the protagonist of one of Giordano’s photos. To put my personal crashes at the service of art. Because I recognize myself in his imperfect women full of contradictions: ladle in one hand, stiletto and ostrich feathers in the other. Cracked but happy. I take home a 15x15 print and a reflection that I share with you: once again, where there are no answers there is art, which teases us, makes us think, sparks debates in the newspapers or around an aperitif, and in the end leaves us with the priceless satisfaction of having spent a splendid afternoon.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.