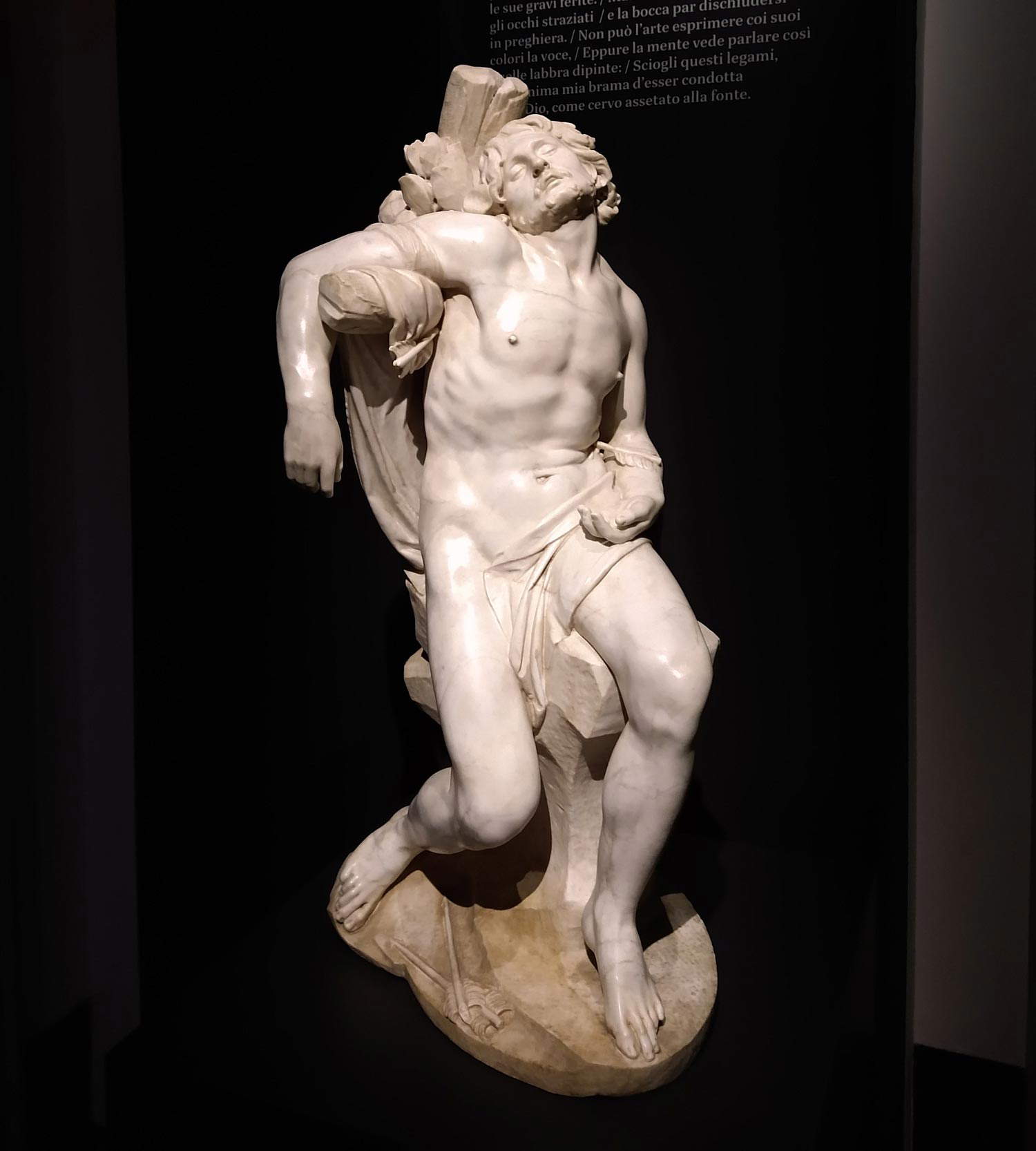

The debut of the current exhibition on Pope Urban VIII at Palazzo Barberini is in the sign of St. Sebastian, a figure who had a particular relevance for the Barberini family and Maffeo in particular. In a close dialogue we find juxtaposed Ludovico Carracci’s St. Sebastian thrown into the Cloaca Massima (1612), from Los Angeles, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s marble St. Sebastian (1617), privately owned and on long-term loan to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, and, reproduced on a wall behind the sculpture, a Latin composition by the pontiff dedicated to the saint. If one looks closer, however, or rather if one reads the work’s caption, since noticing it on one’s own is practically impossible, one realizes that Bernini’s Sebastian is not marble at all, and it is not the original: it is a very high quality copy in painted resin, commissioned from Factum Arte for the exhibition, after the original had been denied from Madrid for conservation reasons.

The use of a “new generation” copy was deemed indispensable in view of the exhibition’s purpose (that of also recounting the very high-profile patronage that Maffeo Barberini promoted even before his election to the throne of Peter, with commissions to artists such as Bernini, Carracci and Caravaggio) and in order to document at the highest level, albeit in copy, the start of that extraordinary association between Maffeo and Gian Lorenzo that bore memorable fruits to Rome and the world. It is curious, moreover, that the highly accurate reproduction is on display precisely in an exhibition on Barberini’s Rome, in which from several points of view the copy assumes prominent importance. The collectors of the time, and the Barberini themselves, had in their collections numerous copies, exhibited together with original paintings, appreciated as instruments of diffusion and appropriation of iconographies and famous works, but also for their aesthetic value, in the case of good quality copies.

At the same time, the different market value of originals and copies was well understood, and in his Considerations on Painting Giulio Mancini dispensed warnings on how to distinguish one from the other, with an attention to analysis and comparison of details that make him a forerunner of modern connoisseurs. Copying was of fundamental importance as a documentation tool (see those of medieval mosaics and frescoes ordered by Cardinal Francesco Barberini and the woodcuts depicting fourteenth- and fifteenth-century tomb slabs commissioned by Cavalier Francesco Gualdi) and had an’unquestioned centrality in the scholarly enterprises of the time (beginning with Cassiano Dal Pozzo’s Museo Cartaceo) and in the exchanges between scholars and antiquarians that constituted the connective tissue of the République des Lettres, to which two drawings from the Portland Vase on display in the Roman exhibition refer. Copies were indeed the cross and delight of scholars, who often complained about the unreliability of drawings and sought more faithful ways of reproducing small antiquities (“impressions” in lead, plaster or sulfur). We are amply testified to these aspects by the endless correspondence of the “champion” of the République, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, who in particular, writing to Cardinal Francesco Barberini on February 6, 1637, reasons at length about copying.

Provençal once again provides us with evidence of his acumen, coming to glimpse, well ahead of his time, the serial nature of much classical art: “[...] by example of the painting of Michelangelo’s Judgment, the sculpture of his Mozè, et so of Titiano’s Magdalene, et other more singular of the century, which if well they are copied, or drawn, or sculptured by different painters or sculptors, nevertheless they always retain the name, of the Giudicio, or of the Mozè of Michelangelo et of the Maddalena of Titiano, as the same prototypical originals. If well they are of another hand, and of another matter, as when the Mozè of Michelangelo was printed in copper, or in wood, or when it was similarly printed, or painted in oil, or in glue, or in miniature, his Judgment taken from that made in fresco in the chapel of Sixto. Thus in the medals of Alexander the Great, one sees the statue of Phidia or Praxiteles (from which the name of cotesto Montecavallo comes) [...]. Not doubting that one does not find there and throughout Greece several marble figures, and low reliefs copied one from another antiquely, just as in the intaglios I remember having seen up to three or four copied oneone on the other of different mastery and in different gems, which could at that time be recognized and similarly named from the design of the primitive sculptor” (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Cod. Barb. Lat. 6503, ff. 195r-v).

But let us return to current events. The use of copies that are practically indistinguishable from the originals seems to be an acceptable choice, provided that it is adopted in a limited number of cases, and always on the basis of very strong reasons (e.g., for the reintegration of compromised contexts, as happened with Caravaggio in Palermo and with Veronese in San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice). If only because these kinds of copies have very high costs of making them. And because perhaps hypothesizing exhibitions made only of auteur “fakes” would not make much sense, except to spare the works stressful travel (if the intent is to give rise to educational exhibitions, reproductions of good workmanship but which in no way can be mistaken for the originals may suffice; I am thinking of the “impossible exhibitions” on great masters of painting such as Leonardo, Raphael, Caravaggio made with 1:1 of the paintings backlit, exhibitions in which, however, precisely the didactic and communicative aspect was not always given the necessary attention).

There is then the problem of what to do with the super-copies once the exhibitions have closed their doors. The most sensible thing is for them to remain with the museums or at any rate with the owners of the originals, who can lend them out when necessary, since ancient works cannot be moved. However, this is not always possible. A borderline case is the stunning reproduction of Raphael’s tomb at the Pantheon, which opened the Scuderie’s (ill-fated) exhibition for the Sanzio Year (2020). The grandiose, life-size copy might have made sense at the opening of an exhibition that was set up on the occasion of the five-hundredth anniversary of the painter’s death, and which took its starting point precisely from the artist’s untimely death and his post-mortem fortune. When the exhibition was over, the copy was shipped to Raphael’s hometown of Urbino and placed in the middle of the church of Santissima Annunziata, near the entrance. The enormous bulk prevents the view of the church’s nave from the entrance, and in general the architectural space is mortified. The solution, it is clear, is not at all satisfactory: the fake is placed before the real of a sacred building not of the most celebrated, but with its own story to tell.

This contribution was originally published in No. 18 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.