If an ancient church becomes a venue for contemporary art exhibitions, how blurry is the line between a layout that respects its spaces and one that is instead heavy and invasive to the point of spoiling the perception of the spaces? Increasingly, buildings built centuries ago are changing their uses by lending themselves to mutations, more or less successful, into exhibition venues: in this sense, long and fraught with reckless set-ups is the history of the church of Sant’Agostino in Pietrasanta, a case that could be taken as an example for its long exhibition history, studded with successful episodes but also, and perhaps even more, with projects to be recorded in the notebook of practices to be avoided with the utmost care.

The bottom of the well was reached, in all likelihood, in 2008, when the austere nave of the church was transformed into a sort of film festival red carpet : red carpets spread on the large marble slabs of the floors to expose to the public the sculptures of Gina Lollobrigida, welcomed at the inauguration by a crowd that would never again be seen for an exhibition in the town of Versilia. From the 1990s to the present day (the most recent chapter being the Africa Tunes exhibition, which opened last Saturday, and whose layout will be discussed below) hundreds of exhibitions have passed through here, organized at a rapid pace: the public hardly had a chance to see the ancient Pietrasanta temple empty, a severe Augustinian church built in the 14th century that still preserves its Gothic facade, reminiscent of that of the Cathedral of San Martino in Lucca. The interior, altered between the 16th and 17th centuries, preserves valuable altarpieces from 17th-century Tuscany: there is a Madonna of Grace masterpiece by Astolfo Petrazzi (who was also commissioned to fresco the adjoining cloister: eight lunettes survive today of his work), there is a Crucifixion by Francesco Curradi, there is a Madonna of the Rosary variously attributed to Cesare Dandini, Jacopo Vignali and other artists of the time, there is a Madonna and Child by Tommaso Tommasi. On the walls, fragments of the original 14th-century decoration, on the altarpiece with theAnnunciation attributed to Matteo Boselli, and behind, in the apse, theCoronation of the Virgin by Jean Imbert. Of exceptional importance, then, is the altar that preserves the three fragments of the Nativity by Zacchia da Vezzano, a remarkable altarpiece from 1519, stolen in 1921, torn to pieces on that occasion, and then found in shreds: today the altar displays what remains of it, in the expectation that sooner or later the rest of the altarpiece will also be found.

It is a walk along four centuries of Pietrasanta’s history, useful for understanding the importance of this seemingly marginal area of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany to which the fate of the town was for a long time linked. A walk, however, that is made possible only with the permission of the individuals who, periodically, organize exhibitions inside the church, which is currently suspended for worship. The St. Augustine complex (the former Renaissance convent, it should be noted, is still preserved intact in its architectural structure) has been the property of the Municipality of Pietrasanta since the time of the Napoleonic suppressions of the monastic orders, and today it has become a venue for exhibitions, including the church. This is the most recent chapter in its history: in the 19th century it was the site of a school of the Scolopian fathers, which remained active until 1880, after which officiating continued in the church, while the monastery fell into a state of heavy decay until the entire complex was restored between the 1970s and 1988. Following this, the municipality opened the headquarters of the Museum of Sketches and the Municipal Library there, leaving the first floor of the convent and the church open to exhibitions. And the church of St. Augustine, with its ample volumes, its sober apparatuses, its altars, its tabernacles, has evidently stimulated the imagination of exhibition organizers who, for some time now, have been continually subjecting it to every facet of use and abuse, often tormenting it with the most far-fetched nuisances that a curator’s brain can give birth to, trampling on its history (literally: ancient tomb slabs can indeed be seen on the floors), preventing the altarpieces from being seen or leaving them in total darkness, treating this layered building as if it were the most neutral of white cube galleries.

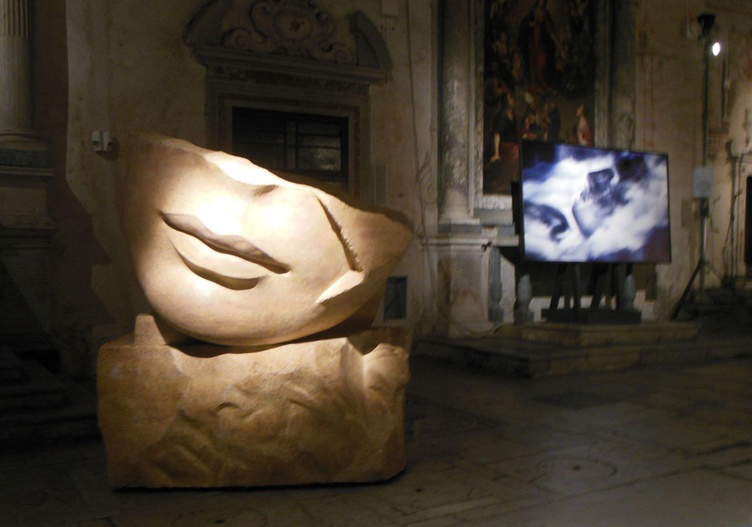

Over the years, the church of St. Augustine, thus transformed into a singular exhibition venue, has essayed in spite of itself a full sampling of impactful installations. It must be said that the house of worship has been the site, above all, of sculpture exhibitions, partly because this is the main artistic vocation of the area, and partly because setting up a sculpture exhibition inside a church is much simpler and more delicate than stuffing drawings, paintings, and squares into it, as has nevertheless been done repeatedly. Nevertheless, there was no shortage of sculptors who invariably wanted to make their presence felt. The notebook of grievances could begin with Igor Mitoraj’s 2015 exhibition, which literally invaded the nave of St. Augustine’s with outsized works, arranged everywhere, in some cases even positioned in such a way as to impale the seventeenth-century paintings. Literally mammoth sculptures also for Stefano Bombardieri, who in 2009 set up a kind of forgettable zoo of gorillas, elephants, rhinos and assorted pachyderms in front of the high altar. Even worse was Medhat Shafik’s 2008 exhibition, when the Egyptian artist’s sculptures had cluttered almost all the available space, perhaps touching the apex of clumsy and rambling cluttering. And again, in 2022, the seventeenth-century altarpieces were obscured almost completely by Martín Romeo’s videos, projected on huge screens that prevented the ancient works from being seen, partly because they physically covered them, partly because the church had been left in total darkness. Not to mention Giuseppe Carta’s 2017 exhibition, when the works of Petrazzi and colleagues were covered to make room for Carta’s (a kind of unicum: I don’t think anyone has ever had the chutzpah to replace the ancient works) and the entire church was turned into a kind of private club.

Artists who have instead granted smaller works to exhibitions have often focused on quantity, turning the nave of St. Augustine’s into a forest of totems: Maurizio Toffoletti’s 2009 exhibition seemed to be at Stonehenge, entering Paolo Ruffini’s 2015 exhibition (one of the worst) seemed instead to find oneself on the set of Hitchcock’s Birds with the church overrun with seagulls hanging from the ceiling and nets scattered in front of thealtar to simulate cages, while at the 2019 Umberto Cavenago and Bart Herreman exhibition, which had also been respectful of the church, bollards had been put up for some original reason to prevent the public from approaching the left side of the nave. The last case, in order of time, was Design Week 2023, which filled the floor of the nave with lamps, small tables, and armchairs that took up most of the available space.

The most impactful exhibitions, however, have been those of paintings: since a painting is not like a sculpture that you can put wherever you like and that stands on its own, but you have to hang it from a vertical support because of its physical evidence, and since for obvious reasons it is not allowed to attach paintings to the walls of the church, the organizers have long had to sharpen their wits to solve the problem of making a painting stand up straight inside an empty space. With the Botero exhibition in 2000, two tall wings had been created that followed the course of the nave, transforming the church into an improvised gallery, and the same model was followed at the 2016 “quasi-Dalí” exhibition, with the aggravating factor that in that case some particularly importunate sculptures had also been added to disturb the perception of the church. In the mid-2010s, the opposite orientation was fashionable for some time: large parallel walls placed transversely to the nave, to be followed serpentine style (so were, for example, Franco Miozzo’s 2014 and Francesco Stefanini’s 2015 exhibitions), in some cases with the provisional elements crudely resting on the ancient tombstones. Of course, not even the façade was spared: it will be worth mentioning, as examples from which to steer clear, Tano Pisano’s “Meccano” of 2021, an exhibition that filled the arches of the exterior façade with inappropriate colored mosaics (not to mention the pile of objects inside: if there were a ranking of the worst installations, this exhibition would be an excellent candidate for a possible top 5), the aforementioned Ruffini, who had a sort of three-dimensional elaboration of the title of his exhibition put in front of the church’s entrance, and the American Fred Nall, author of heavy and clumsy interventions both outside and inside the church.

Was there, in all this, anyone who respected the church of Sant’Agostino? As for sculpture, finding exemplars is quite simple: the most suitable and delicate set-ups, which avoided as much as possible to interfere with the church, were those of the exhibition Tempo by Bertozzi & Casoni (2021), who had the shrewdness to bring a very limited number of works, small in size, and able not to alter the perception of the environment. The same applies to Roberto Barni’s 2013 solo show: again, few works and little disturbance. On painting, on the other hand, it is much more difficult, for the intrinsic reasons of the medium, to find set-ups that somehow did not have a significant impact on the church. A good solution was the one attempted, I think for the first time, for the Africa Tunes exhibition that opened last Saturday: the organization had the problem of incorporating the large squares by the Ivorian artist Aboudia into the itinerary. And instead of pulling up heavy ephemeral walls, wooden frames were installed, positioned not in the center of the church, but along the walls of the nave (just as had been done for Marco Lodola’s 2006 neon lights, another low-impact exhibition), capable of giving the impression that the paintings were floating in space, and placed in such a way as to leave the frontal view of the seventeenth-century altarpieces unobstructed. The element placed in front of the altar, had it been full and not empty like the frames chosen for this exhibition, would have irreparably compromised the perception of the space of the apse: a comparison can be made with Raffaele De Rosa’s 2019 exhibition, where a full wall was installed at the beginning of the chancel (thus in a much more advanced position than the frame with Aboudia’s painting) obliterating almost the entire space behind and affecting the perception of its depth. It may then be said that Aboudia’s painting covers part of the high altar: this is true, but at least a pioneering attempt was made to set up a painting exhibition in St. Augustine’s that would leave the space free for those who enter the church interested.

Now, it will be appropriate to recall that the Municipality of Pietrasanta grants the spaces of the church, asking the concessionaires to respect a regulation where, basically, it is prescribed not to intervene with set-ups that would damage the spaces (thus prohibiting the attachment of nails, the introduction of liquids, the carrying of elements that exceed a certain weight, and so on). In cases of particularly complex set-ups, the project must be submitted to the Superintendence for authorization. The Superintendence, of course, does not express an opinion on the aesthetic quality of the installation: in this case, everything is left to the good sense of those organizing the exhibitions, who are free to decide whether their cultural proposal makes sense inside a church or not (to be clear: those who, like Bertozzi&Casoni, reasoned about time and the fleeting nature of existence inside a church made sense; those who instead filled it with various livestock treated the church as a backdrop). It would not be an excess of dirigisme, however, if the City of Pietrasanta were to ask even to minimize the encumbrances of the exhibits in order to make sure that the church of St. Augustine receives appropriate consideration.

The Pietrasanta exhibition proposal has distinguished itself, especially in the last few years, by a certain discontinuity that has led to the alternation of exhibition events that are anything but interesting (the maximum example, still cited by the inhabitants and well present in their memory, is that of Gina Lollobrigida’s sculptures) to others of much more significant scope and decidedly higher quality. While waiting for Pietrasanta’s exhibitions to reach a more harmonious uniformity of quality, we could start with the basics: to avoid Sant’Agostino becoming an amusement park, where each time the public without knowing whether, in addition to contemporary art exhibitions, they will also have the opportunity to admire the vestiges of the past, with the right spaces, the right lights, without interference. The coexistence of ancient and contemporary cannot be separated from a reflection on the subject.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.