Bulgari Prize 2024 finalists: art that doesn't really impact

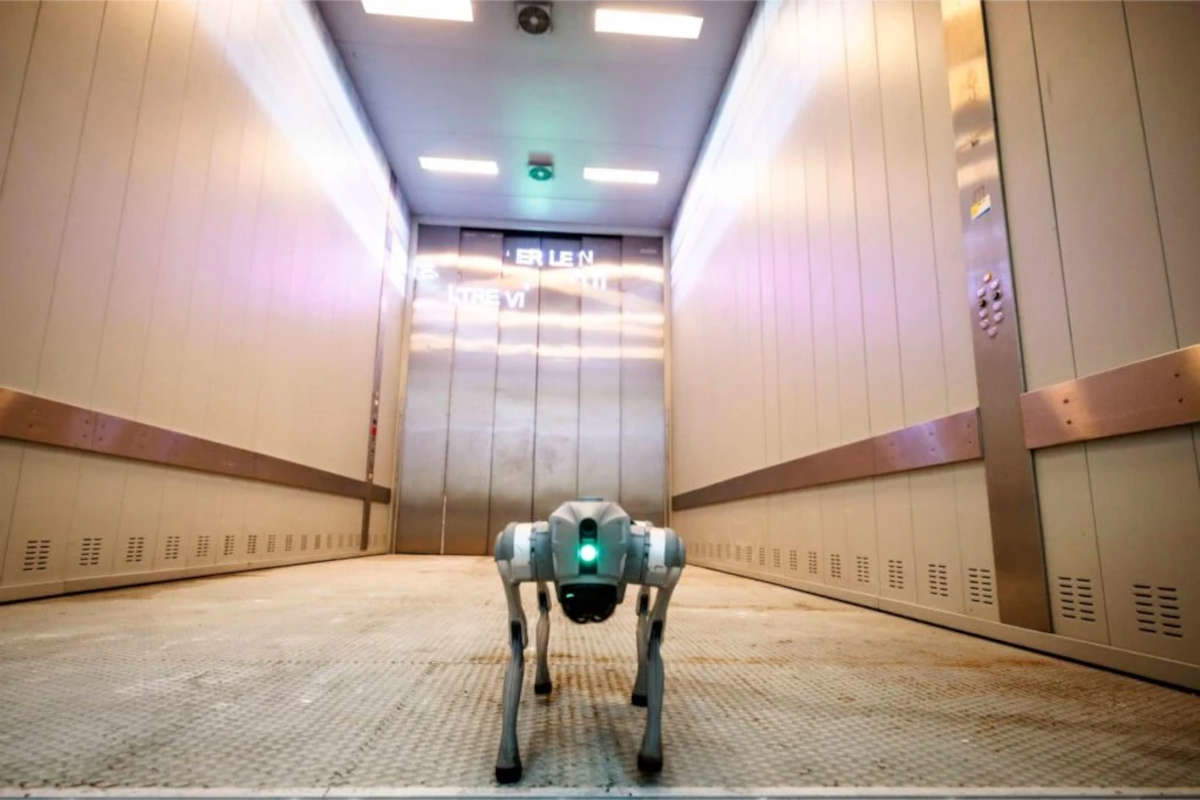

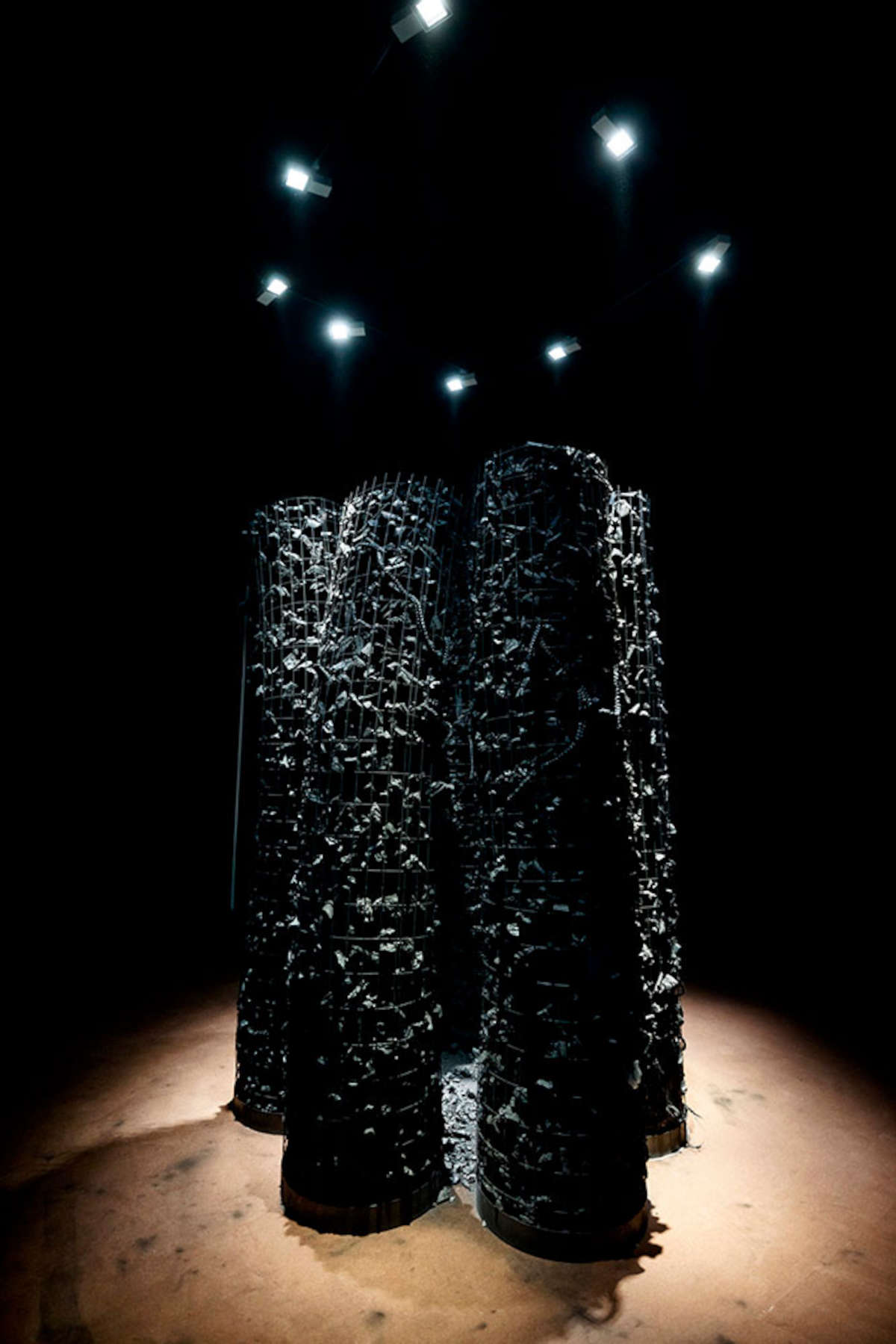

The three finalist works of the Bulgari Prize were presented in Rome at the Maxxi Museum. As has been the case periodically for the past few years, a few curators indicate a few artists and then an international jury defines the short list of finalists. We find the robotic dogs of Riccardo Benassi (Cremona, 1982) performing choreographies guided by mysterious dystopian scenarios. Binta Diaw ’s (Milan, 1995) columns of charcoal, which thus commemorate as many women from the Senegalese village of Nder who in 1819, more than 200 years ago, decided to die by setting themselves on fire to avoid slavery following the Moors’ invasion. And finally, iron panels carved by Monia Ben Hamouda (Milan, Italy, 1991), which feature exotic-arabolic motifs surrounded by spices on the wall and floor.

It must be premised that these awards and reconnaissance can only take a snapshot of the state of contemporary art, and thus always represent a significant litmus test, a thermometer of the situation. In Benassi’s work, technology seems a winking virtuosity and an end in itself that fails to become a useful bridge to address the present and tell us something with respect to our contemporaneity. Suffice it to imagine that these themes have been addressed and cleared through the entire cinematic imagination of the last thirty, forty years, starting trivially with the first Robocop, which dates back to 1987, when Riccardo Benassi was just 5 years old. It is all very well to use the most up-to-date technologies and to detach oneself, at least once, from the Young Indiana Jones Syndrome (although Robocop by now can already be defined as a kind of archaeology), and leaving aside the usual reworking of Arte Povera and the antiques market under the house, but this is not enough to read and deal in an interesting way with our contemporaneity.

Contemporaneity does not need imagery and technological materials, it needs ways, attitudes, visions and attitudes to deal with the present. What do Benassi’s robotic dogs tell us? Nothing beyond moving and dancing commanded by an unspecified artificial or human intelligence. What does the artist want to tell us beyond putting in a predictable 1980s B-movie set design? Does he want to highlight the disturbing danger posed by new technologies? In 2024, do we really need to enter a contemporary art museum to reflect on these issues that have characterized our lives for many years now? By now, even “reflecting,” like “criticizing,” can be done in a thousand ways. Artists should ask questions but also find “solutions,” highlighting precisely ways and sensibilities to represent our present and, if anything, resist it.

Continuing with the works of Binta Diaw and Monia Ben Hamouda and immediately taking three steps back, we realize that these Italian artists, but with African origins, called “second-generation,” seem to become like those “exotic jewelry” that the colonizers, between the 15th and 19th centuries, brought to the Western courts, now represented by art audiences and collectors. Binta Diaw’s coal columns immediately recall the coal of Jannis Kounellis (Arte Povera of the 1960s), and are loaded with significant rhetorical and forced memorials. Why did the artist want to recall this dramatic fact dating back more than two hundred years? Why not the war in Gaza or the war in Ukraine? Or thousands of other injustices that have been committed in human history? Is it enough to present coal by declaring a connection and a quote, at least a forced one, to address the issue of feminism and racism? It seems that the Western taste and market system asks these artists, of African descent, to cleanse our consciences in a hasty and superficial way. Is this instrumental commemoration respectful to the viewers of the Maxxi Museum and to those women who more than two hundred years ago were forced into such a tremendous choice?

If we look at Monia Ben Hamouda’s arabesque panels, the feeling is the same. The Italian and Tunisian-born artist presents us with symbols, scriptures, signs and spices, from the Arab imaginary. But is the artist aware that viewers can understand almost nothing and can only see those patterns as if they were exotic imagery? Culture thus becomes a fetish, an exotic object, and not a bridge. If this was the intent the artist misses an oppositional stage, for the “other and different” culture becomes precisely a devious device for a new form of complacent colonialism. Both Diaw and Ben Hamouda look precisely like complacent victims and actresses of a new self-induced colonialism. Their presence reassures the intelligentsia and the viewers without any possibility of real insight toward Arab culture or relations with feminism and racism in an African key. But again, the mention of racist fact or the Arab code is not enough to address racism, feminism and Arab culture. These women artists probably need to clarify within themselves: do they want to limit themselves to the reporting of the facts and become decorators of a kind of “Exotic Ikea,” a kind of “Maisons du Monde,” or do they want to become witnesses, with their works, of ways, attitudes, visions, attitudes to deal with Other culture in global terms or the important issues of feminism and racism?

They also look at the work of Riccardo Benassi it seems that these artists lacked a critical oppositional phase in their formative stage. As if their “thesis” has never been able to find any critical “antithesis” and thus arrive at synthesis, at works of art that are truly incidental.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.