For the past few weeks, there has been discussion in the United States around a lengthy article by Sean Tatol, founder of the website Manhattan Art Review, on which the young critic reviews, with epigraphic and pungent writing, and always assigning a rating from 1 to 5, the exhibitions he visits each week in his city, New York. The piece, published in The Point magazine, is titled Negative Criticism and is an articulate, lucid, at times merciless snapshot of the state of art criticism in America: natural, then, that it should provoke debate and attract responses (Italian radars, on the contrary, seem not yet to have intercepted it). The reader who follows the American scene little will perhaps feel a hint of bewilderment in noting that the problems focused on by Tatol are the same ones that are sometimes discussed in Italy as well: the fact that there are no spaces for quality-based reviews, the growing hostility toward the practice of judging, the rejection of negative criticism, the frequent habit of using interpretation as a way of evading evaluation. These are all symptoms, clearly recognizable and everywhere widespread, of the disease from which criticism has long suffered, about which so much has been written, including on these pages, and to which it will be convenient to return later. However, the focal point of Tatol’s writing, from which all his arguments descend, is another, and concerns the very nature of criticism: I think it is worth centering attention on this issue, trying to address it with as much clarity as possible.

In a nutshell, and simplifying to the bare minimum, Tatol asks how it is possible to evaluate a work of art. Curiously, in the first part of his article, the founder of Manhattan Art Review stigmatizes what he calls “subjective absolutism,” or the tendency to reject criticism as a result of the idea that art is a subjective experience, both for those who produce it and for those who observe it: no two people can ever exist who, when confronted with a work of art, will have the same experience. Yet, Tatol argues, we know the world through judgments, and a critic who wants to make a judgment should aspire to be objective, or at least correct, according to his or her own knowledge. What differentiates a critic from a casual commentator seems to be, according to Tatol, the amount of experience the critic has accumulated: “a critic is defined by his taste rather than by any consensus or canon, although these are not entirely separable. The point is not that the reader completely submits his or her judgment to that of the critic, but that he or she recognizes and respects the idea that the critic’s sensibility represents some understanding of the scope of his or her argument, albeit in a contingent and individualized way.”

I used the adverb “curiously” just above because, however much study and experience help reduce the degree of subjectivity an art critic expresses in judging a work, perhaps the internal consistency to which the critic subjects his or her judgment is but one part, and probably not even the most important part, of his or her activity. By deferring judgment to unspecified logics of internal coherence that would have to be refined with experience, and by considering art criticism as the “documentation of thought about art” (so Tatol), one might wonder where such coherence might come from and what accumulation might form that documentation. When, on Artnet, Ben Davis states that the emphasis should not fall on the critic’s ability to make judgments of quality, but on the basis on which he or she builds his or her judgment, it brings to mind what a hundred years ago Giuseppe Rensi, in La scepsi estetica, called “the paradox of aesthetic education.” “We want to educate ourselves in taste, that is, to educate ourselves to be able competently to judge works of art aesthetically. To do this we must take as our model and criterion of taste those very works of art which then, once educated, education should enable us to taste competently i.e. judge aesthetically. But, then, it is quite natural that once we proceed in this way, at the end of education those works will seem to us, in every way, beautiful.” For Rensi, there was no solution apart from the clash of the taste of one group of people against the taste of another group. But the level on which to evaluate a work of art is not simply that of personal opinions, and taste does not necessarily become the terrain of clash: it can also be an occasion for encounter, in the sense that a judgment of one person’s taste will not necessarily be valid only for that person, but will likely meet with the favor of many other individuals. It is the Kantian concept of subjective universality, that idea whereby we would be genuinely surprised if someone said to us, say, “I don’t like sunsets over the sea”: this feeling of instinctive and instantaneous wonderment would arise because it is generally believed that the beauty of a sunset over the sea represents an indisputable fact.

On the judgment of taste, perhaps Negative Criticism tends to confuse the plans a little. I believe that the evaluation of a work of art essentially follows three levels of judgment: a historical judgment, an aesthetic judgment, and a judgment of taste. When Tatol writes that Piero della Francesca was “incompatible with the Victorian sensibility of Ruskin’s generation,” he is taking the matter to the level of judgment of taste. On the other hand, when, further below, he writes that the critic can discover new ways of seeing art stating that the artist’s subjectivity extends beyond his intentions, and that he will therefore be able to see that Piero della Francesca’s “geometric rigor heralds tendencies that will be taken up five hundred years later with minimalism”, has already slipped to the level of historical judgment, since it is no longer a matter of assessing how much an ancient work is consonant with the sensibility, and therefore the subjectivity, of a modern artist, but it is a matter of considering the resonance of his lesson, the scope of his art. In other words: Victorian England harbored no special regard for Piero della Francesca, but it cannot be denied that Piero della Francesca’s art had an extensive impact on his generation, on the next generation, and was capable of bouncing its echo even centuries later, whenever the cultural conditions would be created to accommodate his lesson (in the seventeenth century theart of the great Biturgensian had little importance, while on the contrary metaphysical painting perhaps would not have existed without a Piero della Francesca).

One could object by opposing the argument that a given artist exerted a given impact on a given epoch for mere reasons of taste: to a large extent this is true (should one wish to understand the concept of “taste” not, vulgarly, as one’s preference for a given artist, but as one’s way of seeing and consequently appreciating him or her), but we have already left the field of subjective taste and entered the field of intersubjective taste; we are walking on the ground of comparison from which traditions arise. It is undeniable that there can be no infallible and totally objective criticism, since even the aesthetic judgment that wants to be as as aseptic as possible turns out to be ineluctably conditioned, at least by the cultural structures of one’s time. However, in critically evaluating a work of art, personal taste should not be a category into which one’s judgment should fall: if one writes that Jacques-Louis David and Ingres are not compatible with one’s own, personal sensibility, I believe one is doing exactly what the critic should not do, if the purpose of the critic’s activity should be to help the public navigate their way through the artistic productions of their time, and not to condition their preferences. This is why “I like” and “I don’t like” can not only be considered two categories that are at the very least questionable for the purpose of formulating a critical judgment (Tatol himself, deploring “subjective absolutism,” is aware of this), but they run the more than real risk of misleading the reader and fueling confrontation rather than openness to confrontation. As far as I am concerned, there are artists whom I consider extremely interesting, whose paintings, however, I would never hang in my house. Conversely, there are artists who perfectly meet my personal taste, but whom, on the contrary, I consider uninteresting or unimpressive.

As for the historical judgment, on contemporary art it has some obvious limitation, mainly due to the fact that in front of a work produced today, yesterday or the day before yesterday one finds oneself provided with a lower casuistry than that available for ancient works: one can suspend a possible evaluation arising from the impact that a work has on the contemporary scene (it could also be due to passing fashions), but one could attempt a judgment on the basis of the degree of innovation that an artist introduces with his work. Trivializing, I think one can safely be wary of those who believe, for example, that one needs to wait time to understand whether Maurizio Cattelan’s art will “remain” (moreover, those who oppose this argument are usually unable to quantify the amount of time it would take to wait to arrive at a correct historical judgment about the artist in question): it is widely agreed that part (and, I believe, not necessarily the preeminent part) of Cattelan’s originality lies in his ability to use “forms of exaggerated realism to represent contradictions, fragilities and vices of the society of the end of the millennium by exploiting an art system increasingly interested in the spectacular value of the work” (I quote from a scholastic art history textbook, L’arte di vedere, recently published by Mondadori).

However, it should be pointed out that originality, if understood not as the genuineness of an artistic product but as its ability to break a given pattern, or at least to introduce substantial novelties, has not always been the prevailing yardstick for judging a work of art. Otherwise we would not explain why a painter like Lorenzo Lotto worked in the provinces all his life. This happened not because he was unknown to most or because he was an outcast: far from it. He trained in Venice, had contacts with illustrious patrons, and Vasari dedicated to him, Lotto still living, a passage in the Torrent edition of the Lives, later further developed in the Giuntina edition. Quite simply, his art was considered far from the aesthetic standards of the time.

Until at least Romanticism, critical judgment was essentially an aesthetic judgment, which took into consideration almost exclusively the intrinsic characteristics of the work of art and was based on the concept of ’imitation, specifically the imitation of a model, which in turn was considered to be all the more perfect the more successful it was in imitating nature, operating, however, a selection on the basis of what is generated in the artist’s mind. The mechanism is explained well by Vasari himself in the introduction to the Giuntina edition of the Lives: “Because drawing, the father of our three arts, architecture, sculpture and painting, proceeding from the intellect, extracts from many things a universal judgment, similar to a form or true idea of all the things of nature, which is most singular in its measures, whence it is that not only in human and animal bodies, but in plants still, and in fabrications and sculptures and paintings he cognises the proportion which the whole has to the parts, and which the parts have to each other and to the whole together. And because from this cognition arises a certain concept and judgment that is formed in the mind that such a thing, which then expressed with the hands is called a drawing, it may be concluded that this drawing is nothing but an apparent expression and declaration of the concept that one has in the mind, and of what others have in the mind imagined and fabricated in the idea. [...] this drawing needs, when it derives the invention of some thing from judgment, that the hand be, through the study and being of many years, dispatched and apt to draw and express well whatever nature has created, with pen, with style, with charcoal, with pencil, or with any other thing; for when the intellect sends forth concepts purged and with judgment, do those hands, which have many years exerted drawing, know the perfection and excellence of the arts, and the knowledge of the artificer together.”

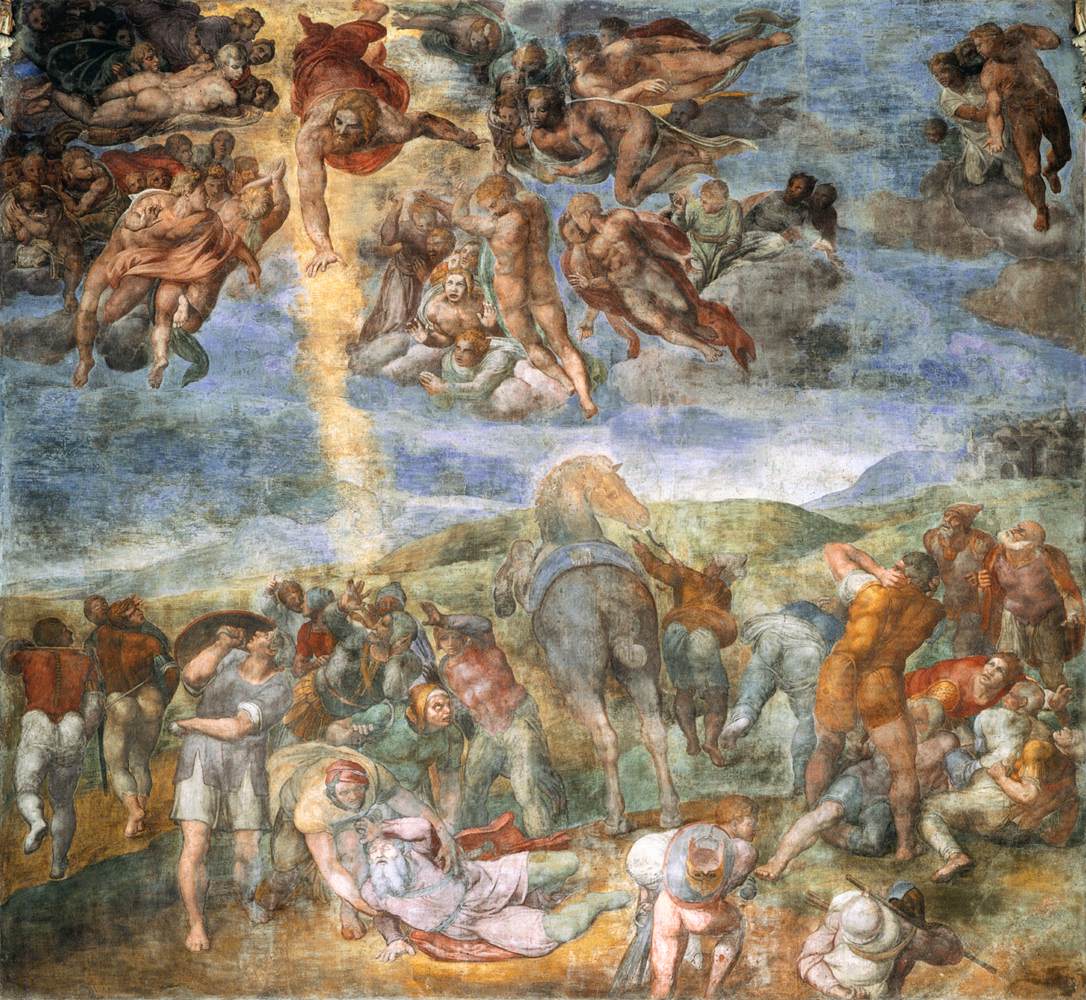

Vasari’s judgment, widely shared at the time, had found in Michelangelo the supreme model, the highest to aspire to (simplifying the reasons to the extreme: for the vigor and perfection of his drawing, for his ability to master all the major arts, for the variety of his inventions, and so on), and an artist was considered all the more interesting the closer he came to Michelangelo. It will be worth mentioning, however, that even at that time there was already a rather vigorous and polemical dissent produced against the idea of Michelangelo as the supreme model: Ludovico Dolce, inAretino, published in 1557, challenges this conviction to affirm that “we must not stop in the praise of one alone having nowadays the liberality of the heavens produced painters equal to and even in some parts greater than Michelagnolo” (Dolce opposed Titian, to whom “alone must be given the glory of perfect coloring which either none of the ancients had, or, if they did, it was lacking, some more and some less, in all the moderns,” and Raphael, by virtue of the characteristic that was reproached against him by Michelangelo’s admirers, namely the simplicity and gracefulness of his inventions: “ease is the principal argument of the excellence of any art and the most difficult to achieve, et è arte a nascondere l’arte”). Not even in the sixteenth century, when the models to look at were not as many and widespread as they are today, did the idea of a presumed infallibility of the critic loom large, not even five centuries ago there was absolute consensus on aesthetic judgments, nor was there any unanimous thought on how to look at art, not even on the basis of a shared scheme: for Tuscans like Vasari the basis for judging an artist’s mimetic abilities was drawing, Venetians like Dolce took color as their reference.

Today we still tend to reason according to the model of originality: a work will be all the better the more innovative it is, an artist will be all the more convincing the greater the amount of novelty he is able to introduce. For the sake of completeness, it should be specified that relying completely on the yardstick of originality entails certain problems: the most obvious risk is that of judging negatively anything that is not considered original, despite the fact that there are many artists who, while working in the furrow of even rigorous tradition, demonstrate talent, if not personality and poetry. Of course, this does not mean that one should put everything on the same level: going back to the sixteenth century, it is legitimate to identify clear degrees of separation between a Michelangelo, a Battista Franco (i.e., an artist of undoubted ability, curious, refined, and, moreover, a very skilled draughtsman, who, however, throughout his career strived obsessively to approach Michelangelo), and one of the many anonymous imitators with no particular qualities. There are, however, artists who, while adapting to illustrious models, and thus working in a manner that could be judged as not very innovative in absolute terms, can introduce interesting novelties within the framework of specific national, regional, or local contexts (much of the study of the history ofart, after all, results in the study of the reception, local scope, and interpretation of ideas and inventions that have arisen in other contexts), they may deal with rare or awkward subjects, and they may certainly be able to demonstrate accomplished personalities, compositional talent, and poetic skills.

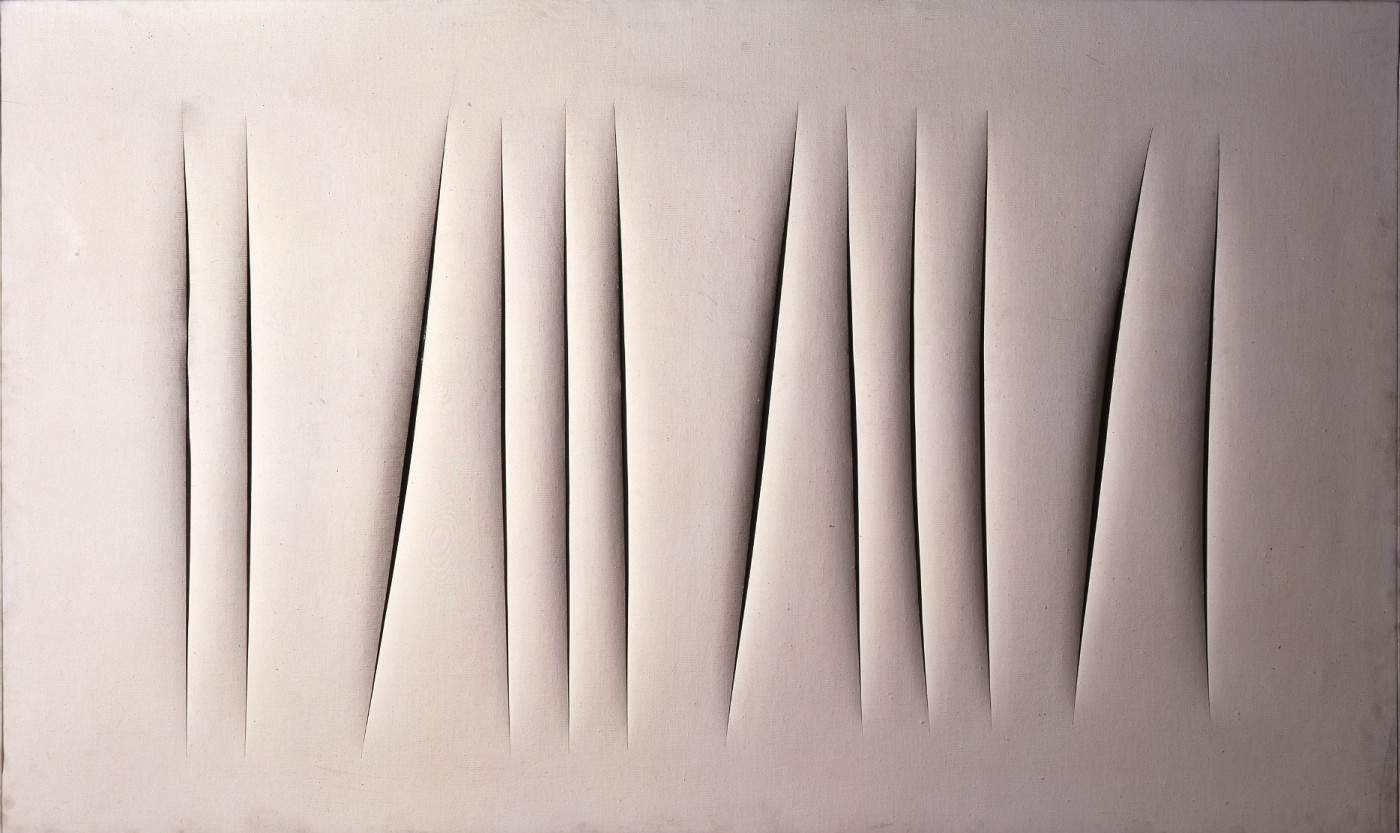

One enters here the realm of aesthetic judgment, that is, that which looks at the formal qualities of a work of art (composition, invention, rhythm, colors, light, design, effects, volumes, proportions) and considers these qualities both for themselves and on the basis of what the artist seeks to convey with the product of his or her ingenuity. One can begin to approach the subject by establishing, for example, that an artist is first and foremost an individual who sees reality differently than one who is not an artist sees it. In the soul of an artist who observes a collection of objects, “each thing,” Ardengo Soffici wrote extremely effectively, “will be arranged and modified with respect to the others, according to a new proportion of the whole, will be subordinated to all the demands of a rhythm, of a harmony Of an intuition, of a poetic will - of a sui generis style, absolutely subjective, proper to the artist.” Hence the idea that the goodness of a work is given by the “quality of emotional and suggestive elements in function of an elementary poetic unity.” It also applies to works that are not concerned with imitating reality, but focus, we might say, on the concept, seemingly simple works that the general public often judges as trivial. Take Fontana’s holes or cuts: By intervening on the pierced canvas, sometimes adding fragments of glass or stones, Fontana created like “constellations opposite those of the holes, sometimes with baroque effects, sometimes creating a kind of balance,” while the cut, “in its absoluteness and precision of creative gesture, allows Fontana to remark not only the conceptual value of the work but above all to create a perfect ’summa’ of existential value and, in the exaltation given by the gesture, of aesthetic-formal value” (so Massimo Melotti). The same reasoning applies to works that might be even more difficult, such as the large installation that Arcangelo Sassolino brought to the Malta Pavilion of the 2022 Venice Biennale: a self-supporting slab of steel that was cast and dropped drop by drop inside seven tanks, according to a precise score created by a Maltese composer, Brian Schembri. The result was a work of rare visual power, which worked because of the extraordinary balance of each of its components and which was able to pay poetic homage to Caravaggio, because the steel was transformed into light through the processes of an artist whose research finds its dimension of intense visionariness in his ability to probe the possibilities of interaction between art and physics.

The dialectic between the originality and quality of the work had already been framed to some extent by Giuseppe Antonio Borgese in his Poetics of Unity (published in 1934, but taking up concepts expressed more than two decades earlier): holding that any work of art includes a certain degree of originality and a certain degree of imitation, and considering that art expresses a personal state of mind and is not art “except insofar as it presupposes the possibility of communicating that expression to other men and insofar as from the contingent it distills theeternal” (in essence, art, for Borgese, by addressing the spirit places itself outside space and time and expresses ideas), the solution would lie in the artist’s ability to create forms that tend toward the universal and to express them “with a form not limited by contingencies.” Borgese did not go any further in formulating his way of overcoming the impasse, but it was still interesting to attempt to put up a barrier to the idea that the work, to be good, must inevitably be original.

How then to tell whether one is faced with a good work, a work of quality? There is no single answer, there are no shared parameters, and above all, the answer involves the persistence of a certain degree of subjectivity that derives from the experiences, studies, knowledge, and even the intuition of the critic, especially when faced with an artist, perhaps a young one, who is seeing for the first time. Instinct, then, becomes the first tool the critic employs in articulating his judgment. I was one day, at one of the most important contemporary art fairs, in the company of a well-known gallerist with whom I had the pleasure of sharing a brief stroll among the stands, during which we confronted each other precisely on the parameters of judgment with which to evaluate works of art. Among the various considerations, one emerged that, at first glance, seemed to me disarming: whoever judges a work must feel something by observing it, must feel it, must turn on the work in front of him. He must like react instinctively, if he can make the point. Of course, this feeling is not equivalent to the (more than legitimate and, indeed, desirable) feeling of the visitor who gets excited in front of a work by Caravaggio or even in front of the work by thelast of the amateurs, if the amateur communicates something to him, if he evokes a personal memory, if he succeeds in touching the chords of his soul (and, mind you, it makes no difference whether our visitor is an insider with years of experience or a tourist entering a museum for the first time). They are two different sensations: we could call the casual visitor’s “feeling” and the critic’s “disposition” (who, in front of a work, may also feel a feeling, except later realizing, perhaps, the superficiality, academicism, or purely derivative character of what he or she is looking at: disposition has to do with this kind of instinctive recognition rather than emotional reaction). Disposition could be defined as the aptitude to perceive the character of what is being observed, and the more the critic will have observed works all the time, the more he or she will have studied, read, attended fairs and exhibitions, operated research among books and on the Web, the more his or her disposition will be trained. This is, of course, not a new idea: going back as far as the nineteenth century, already Baudelaire thought that feeling was the basis of the critic’s judgment.

In the opening lines of his Beata riva, Angelo Conti writes that the artist “is a soul which more intimately than any other can relate to the soul of things,” is an “individual will which gradually cancels itself into a broader and deeper will.” Conti believed, for example, that no one like Segantini had a sense of the mountain, no one more capable of “representing what the mountain expresses with its august stillness,” “the silence that surrounds it,” “the aspiration of its peaks.” Or, that no one like Mario De Maria had been able to recount the “conversations” of moonlight with the cracked walls of a building, with the calm waters of a sea or lake. I think the arrangement has to do with something like that. And it does not necessarily mean recognizing the beauty of a work: classically understood beauty is not the only valid aesthetic category, since one can also aspire to the ugly, the repugnant, the messy. It is a matter of recognizing, in the first place, the degree of innovativeness of a work, and then trying to understand, regardless of whether the work may be original and innovative or not, how profound the artist is in expressing the soul of what he is representing on canvas, with marble, with steel plates, with pencil on a sheet of paper, with video, with whatever medium. Then, after the initial impact, after observing the work according to his or her own disposition, the critic will evaluate other aspects, involving formal qualities, the subject, the context within which the work is placed, its historical position: thus, whether it is a truly new or derivative work (he may not miss something at first glance), whether the aesthetic layout of the work is consistent with the artist’s stated intentions (assuming there are any), whether the work is topical, whether it is superficial, whether it follows a fashion, whether it is able to elevate the artist’s particular to a universal plane. It is at the end of this work, far from instantaneous, that the critic will come to formulate his judgment, to take his position.

It is not easy to condense the judgment on an artist into a few lines: nevertheless, some examples will come in handy to get an idea of how a production could be evaluated. One could start with Bertozzi&Casoni: the astonishment, vivid and genuine, that one generally feels when admiring their ceramic works is but one of the many elements that make their production original and non-derivative. Their work, technically perfect, full of quotations and references to the past, bristling with singular aesthetic traps, eternal and timeless, focused on the universal and vice versa always far from the chronicle, capable of producing other dimensions and merging reality and conceptual, able to open new paths, never attempted before, in the field of ceramic art, a figure among the most innovative productions that Italian art has been able to express in the last thirty to forty years. Then there are artists who are able to revive an established tradition with freshness, and to produce art that resonates in unison with the spirit of their times, or even to anticipate them. Daniele Galliano, for example, with his Neo-Impressionist paintings is probably the Italian painter who best foresaw and recounted the society of mass communication, and then transfigured it into an abstract image that, even in his case, becomes universal. And, speaking of abstraction, among the most interesting researches I think we can mention that of Maurizio Faleni, who starts from Rothko to explore the possibilities of color as a means to reach the supersensible through the sensible. Looking at the young, the name of Andrea Fontanari from Trentino comes to mind, a sort of Mediterranean Eric Fischl who entrusts to his vivid, saturated hues and liquid brushstrokes à la Sorolla compositions that evoke memories, encounters, oblivion.

Then there are researches that are even more inclined toward a tradition but are not unconvincing, on the contrary. At the last edition of Artissima, for example, we were able to appreciate the work of a young South African artist, Mia Chaplin, who at first might seem to be a mere imitator of Cecily Brown and would therefore be to be discarded without appeal if one were to judge her by the sole yardstick of originality, only to find that she is not a mere imitator of Cecily Brown.originality, but then we find that the softer palette, the more delicate expressionism, and the more marked tendency towards figuration, even within the framework of a common Rubensian terrain, contribute in a rather evident way to define her personality. In Italy, a singular temperament is that of Guglielmo Castelli, who on a formal level could remind one of a Peter Doig reinterpreted, however, according to the filter of Italian art of the past (certain artists of the 1930s come to mind, from Pirandello to Birolli), and who, with his paintings, capable of moving on the plane of figuration starting from abstraction, evokes atmospheres of melancholy, decadence and nostalgia. It is useful to point out that, for all the cases mentioned above, we are talking about artists who not only have an open gaze to both an international and a local or traditional dimension, but who are also well recognizable, and the degree of recognizability is perhaps the most immediate evidence for understanding whether an artist has personality, strength, character. Thinking instead of a negative example, one could go back to the work that Germany’s Raphaela Vogel presented at the 2022 Venice Biennale: formally bolshy and derivative (Deborah Butterfield, Sayaka Ganz and on down to Agenore Fabbri’s atomized animals), rhetorical, superficial and anodyne in dealing with the subject, respectable and reassuring in attitude.

It is self-evident that no art critic will be able to administer certainty to the public, neither when the criticism is positive, nor even when it is negative. Sometimes one exceeds in generosity or enthusiasm, at other times one runs the risk of being too rigid or hard on an artist, but at the base there is always the desire to provide one’s own reading: and then the most the critic will be able to do is to share with the audience his or her judgment by trying to be as objective as possible according to his or her evaluative schemes, and above all by trying to be clear (it will be clearer if he or she comes from a journalistic background, since the journalist has to be clear by trade and cannot afford the nebulous digressions that certain curators often indulge in). One has been presented here, without even pretending that it will remain unchanging: it is not certain that from now on the parameters of the writer will not change. What is certain is that the critic may indeed be as objective as possible according to his own yardstick, as mentioned above, but his system of measurement will never be definitive and inappellable. There has never been, nor will there ever be, a totally objective criticism. Criticism, needless and even naive to recall, is not a science. And precisely because it is not a science, the critic will also know how to avoid taking himself too seriously, but he will also know how to write without being cold and detached, showing passion on the contrary, even knowing how to be polemical if need be. One of the greatest critics of the last fifty years, Peter Schjeldahl, wrote, “I will never accept that art criticism is a profession like dentistry. It is rather an area where journalism and literature overlap, like sports writing.” I think it can be considered one of the most fitting definitions of “art criticism.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.