If until a few decades ago the museum debate was oriented between museology and museography, today the consideration of visitors from a psychological and social point of view has become just as important as the enhancement of the identity of the collection, the preservation and display of works. Thus, a completely new idea of the museum has emerged: new but “ancient,” because it has its roots in the birth of the public museum and the opening “to the people” somehow enacted by the Enlightenment.

A theme, this one, that has never stopped and was certified with the new ICOM definition of 2022, which, after a heated internal debate, endorsed the idea of the museum as a place to educate, that can stimulate reflection, learning, where one can have an enjoyable experience and at the same time reflect, paving the way for continuous and endless moments of sharing. An inclusive, accessible, participatory museum. A museum that is also open to the challenges of the present and the future, that looks ahead, that holds firm to the mission of preserving works but must be able to know how to lead them to new and unexplored horizons of knowledge.

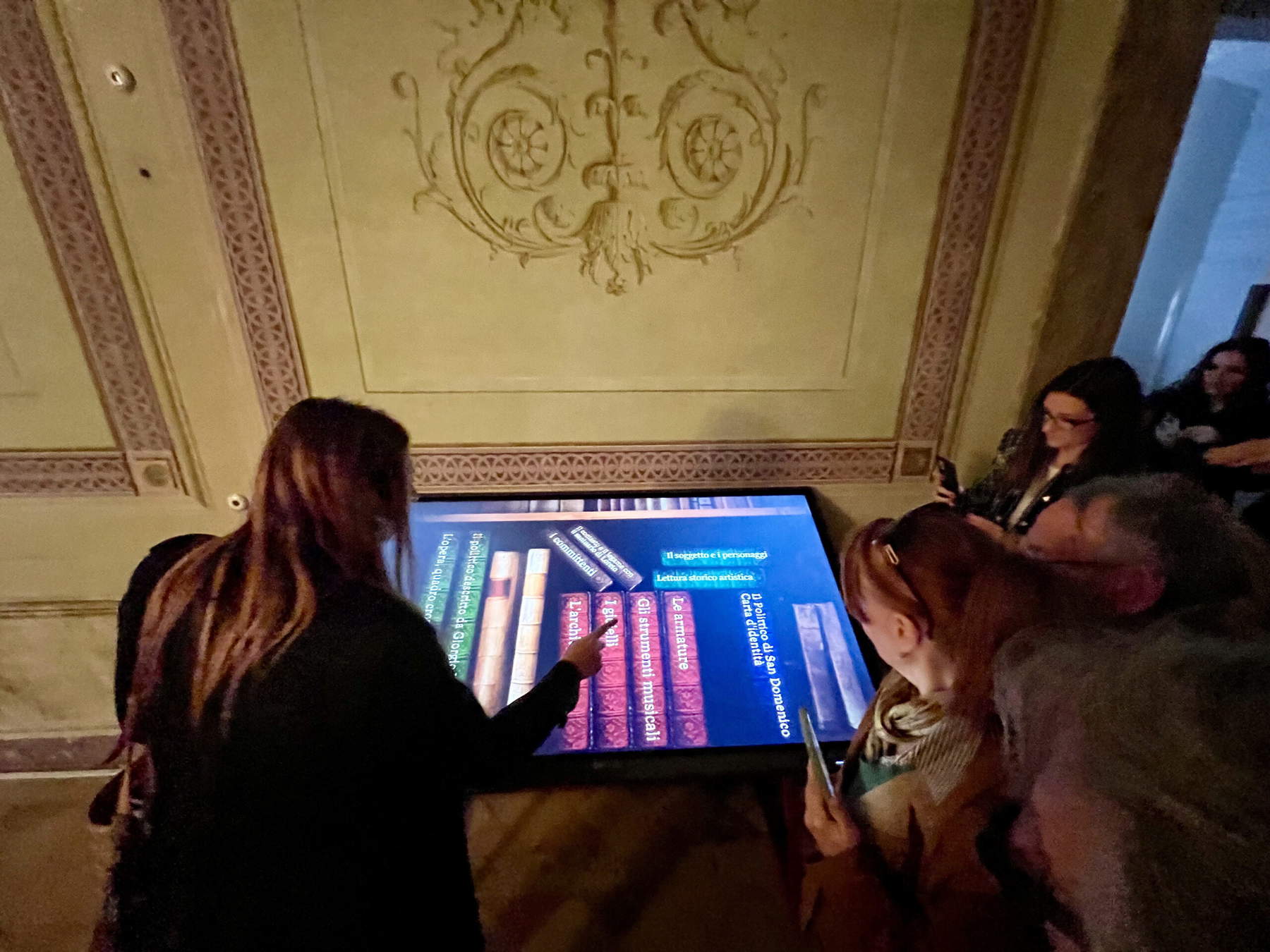

Currently, the use of multimedia and digital technologies contributes to a continuous experimentation of innovative formulas of fruition, adapted to new scenarios and different needs of the public. The museum today is a privileged actor/interlocutor to interpret and develop the paradigms of modernity in the era of digital transformation. How to be ready to carry out this challenge and develop the museum mission as a public service? In the meantime, in full awareness that change affects the entire cultural sector as lucidly understood by a great musician and conductor like Alberto Zedda, who wrote: “As long as opera responded to needs close to current taste, the task of its reproduction was relatively simple, because it was helped by a widespread tradition, capable of suggesting interpretive resources in use... Today, production must be set up considering potential interlocutors not only the audience of subscribers, but the much larger audience that can be reached at home with the sophisticated reproduction tools that a constantly expanding market provides. Forecasts for the future, dominated by the Internet, outline a science fiction world with which even traditional entertainment will have to reckon. To fail to take this into account would be unforgivable recklessness.”

Maestro Alberto Zedda’s lucid analysis, read today in the 21st century, thus compels reflection on the transmission of value that the cultural system as a whole, including live performance and opera music, can express in the contemporary age as it enters fully into the digital age and if it opens up to new scenarîs to grasp and intercept new audiences through emerging and exponential technologies, the science fiction world described by Zedda. Indeed, what is the Internet Zedda speaks of if not that dimension that is now an integral part of our cultural ecosystem, the digital dimension where culture is born, commented on, discussed, shared, contaminated, modified? And how can we read the museum in this new context if not as an ever-evolving laboratory in the wake of its millennia-old tradition that from Greek thesaurus came to narrative museums without works?

On this premise, it is difficult to make a list of what can and cannot be done in a museum. Rather, it is essential to equip each museum with a scientific and authoritative director who can devise, on the basis of the collections present, new models for transmitting the history of the works, finding in each of them an element that lends itself to current readings. Not pursuing models of pure entertainment but of dialogue and participatory confrontation. Not activities for their own sake but always in line with the spirit that hovers in the museum, the deep meaning of its collections. Could we perhaps blame the Beyeler Foundation for setting up an evocative yoga class in front of Monet’s Water Lilies where the work itself becomes a source of meditation? Or the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for anticipating with the digital platform Closer to Johannes Vermeeer the knowledge of every single detail of the master’s work in the exhibition that the public then rushed to visit en masse? Or the Municipality of Recanati for setting up a digital experience dedicated to Lorenzo Lotto where the visitor is greeted by a monitor where an actor playing through a script the master, tells us about his vision of life, art and love for the Marche region deliberately in front of a work by the artist?

Rather, I feel like raising a cry of alarm about the fate of civic museums at times at the mercy, rather than of specialized curators or directors, of aldermen or executives who are experts in other matters and who endorse exhibitions, programs, and activities without a design, a logical line, fueling a progressive dematerialization of the concrete and constant function of the museum as a symbolic place of representation of the community and communities including minorities. I will always remember the excitement about twenty years ago when, while visiting the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, I noticed the captions of the works also translated into Arabic, demonstrating the openness of the management to the city’s Muslim communities.

The crux then, in my view, is the centrality of museum management. Without a directorate, one opens the way to the museum as a place for the preservation of works, or in the worst case, as a place for the representation of activities that clash with the universe it encloses; to the museum where one can register, over time absence of care towards dated layouts, non-conforming lighting of the works, obsolete and neglected educational apparatus.

This danger was, in theory, averted on the front of state museums with the birth in 2014 of autonomous museums with scientific, financial, accounting and organizational autonomy, hailed as an epoch-making breakthrough both in relation to the overall autonomy entrusted and the identification, for each of them, of a director appointed through an international call for proposals. Here, this continued attention to this major attraction should be devoted on an ongoing basis to the civic museums that make up the vast majority of our country’s museums. The danger in fact could be that if a civic museum, for various reasons, and the absence of authoritative leadership is one of them, gradually loses its central role in a community, it may become first an object of inappropriate activities, then an economic burden to be managed and then in perspective to be downsized.

It is always good to keep in mind that already Krzysztof Pomian, ending his trilogy on the history of museums published by Gallimard and in Italy by Einaudi, with the chapter A Long Present. From 1945 to the Present, he emphasized how the pandemic has called into question the economic model based on the growth of museums in every direction. In an interview granted to Il Giornale dell’Arte on the problems and new horizons traced by the pandemic and the global environmental and climate crisis, he concluded with this reflection: “It is to be feared that this is not a passing shock, and if so, the museum world as a whole will have to undergo a profound restructuring, the contours of which are as yet barely visible.”

This contribution was originally published in No. 22 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.