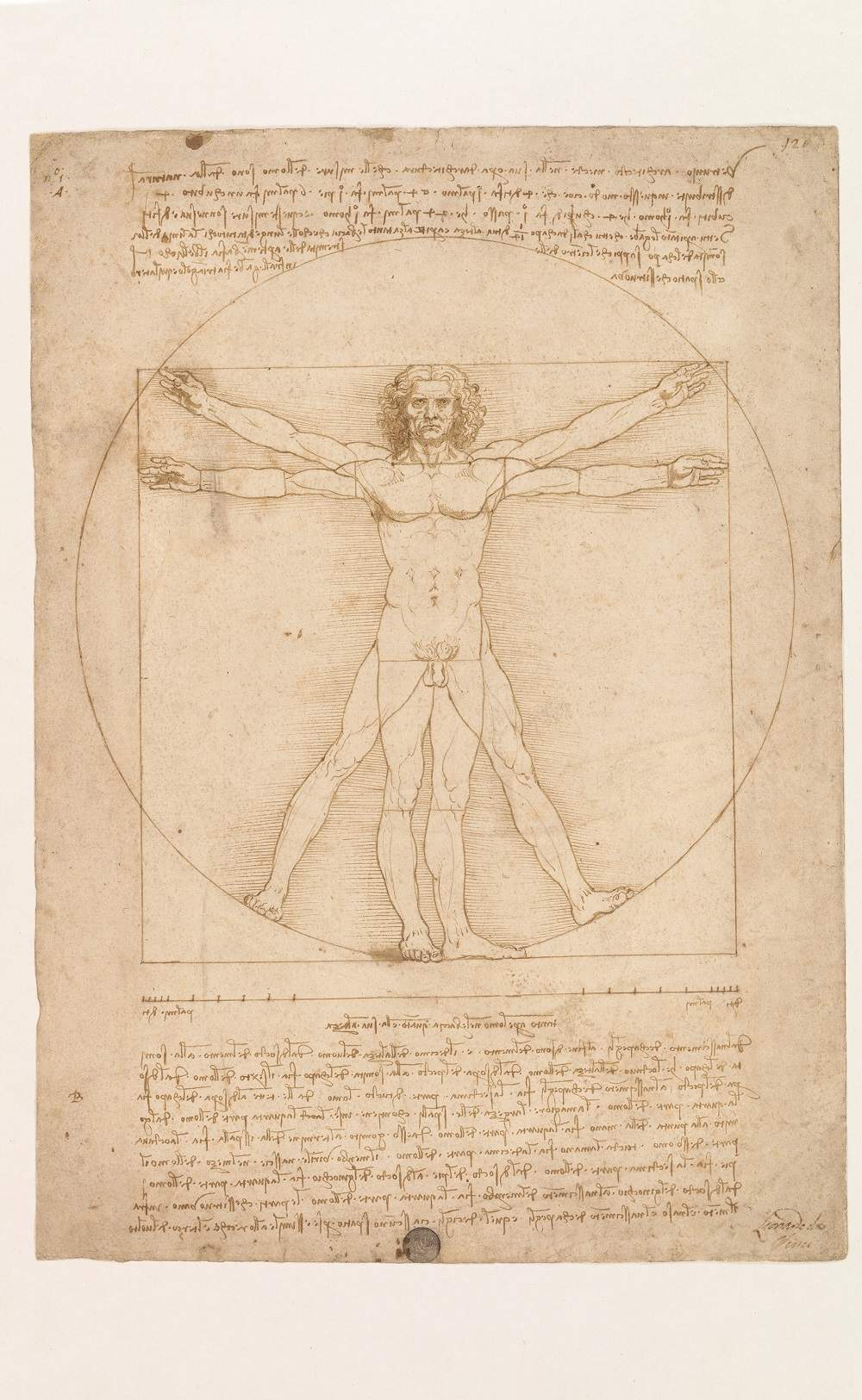

Italy’s latest disputes over the commercial use of images of Michelangelo’s David (GQ and Brioni cases) and Leonardo’sVitruvian Man (Ravensburger case) emerge judicially at the same time that the reproduction of the image of Botticelli’s Venus for the Ministry of Tourism’s Open to Wonder advertising campaign has sparked a heated controversy that has as its backdrop the role of the state as custodian of (humanity’s) cultural heritage.

The decisions of the Venice and Florence Tribunals on such controversies are part of that line of thought that delineates in the head of the Italian state an exclusive right to the image of cultural property1. The protection of this exclusive right would have economic purposes (collecting concession fees and reproduction fees) and not patrimonial purposes (assessing the compatibility of the use of the image with the purpose of the cultural good). This line of thinking finds reflection in some case law precedents and recent regulatory policies of the Ministry of Culture2.

It should be premised that we are talking not only about the reproduction made on the site where the good is kept, but also about the reproduction of a copy found by a third party (e.g., by downloading the image from Wikipedia).

The commonality in the decisions of the Italian courts is extreme conceptual confusion. According to the judges’ adventurous interpretation, the exclusive right would be based on the connection between the Cultural Heritage Code (Art. 107-108) and the Civil Code (Art. 10). Specifically, it would be the link between state power to control the reproduction of cultural property and the right to the image of the person-state.

The overlapping of non-patrimonial and patrimonial aspects, such as the mixing of publicistic (the Cultural Property Code) and privateistic (the personality rights of the Civil Code) legal instruments, as well as the fetishistic appeal to the innocent Art. 9 of the Constitution veil the real interests at stake and the purposes of this new form of pseudo-intellectual property that would like to ground in the head of the state the power to exclusively control the commercial use of cultural heritage images.

This is not a noble battle of the public sector against the falsification of authenticity, the deformation of the cultural identity of the past (of the Nation?) or the impact of contemporary collective sensibility or, again, against the power of big tech and web platforms in controlling the digital dimension of cultural heritage (which, on the other hand, is largely underestimated even with reference to artificial intelligence).

The purpose is anything but: the Italian state plans to enter the market for images of cultural property. This can be seen from the act of address concerning the identification of policy priorities to be implemented in the year 2023 and for the three-year period 2023-2025 (Ministerial Decree no. 8 of January 13, 2023), as well as from the “guidelines for determining the minimum amounts of fees and charges for the concession of use of the assets in consignment to the state institutes and places of culture of the Ministry of Culture (Ministerial Decree No. 161 of April 11, 2023). ”3 The hope is to drain money to replenish public sector coffers. It matters little (to the promoters of the exclusive right to the image of cultural property) that this operation comes at the price of trampling on fundamental legal principles and contradicting the policies of opening up cultural heritage. Such an operation in fact entails:

the evaporation of the public domain by means of a legal monster (a pseudo-intellectual property that escapes the legislative balancing typical of exclusive rights to intangible assets);

violates the principle of the closed number of intellectual property rights;

conflicts head-on with European Union law and international law;

exponentially multiplies transaction costs;

does not guarantee more profits than a free-use regime as noted by the Court of Auditors only a year ago (Resolution No. 50/2022/G);

is largely vague and interferes with fundamental rights and freedoms such as the right to culture and science and freedom of expression and information.

The Italian vicissitudes of the right to image on cultural property can be reread in the key of the most classic heterogenesis of ends. The publicist norms regulating the reproduction by images of cultural goods were intended to control the rival use of the spaces in which the same goods are located and retain a purpose of protecting the physical integrity of the good when new technologies offer no alternative to physical contact with the material object. These functions are complemented by the state’s power to charge fees and royalties where a value-added service such as the provision of high-definition images to the private individual is offered. In all these cases, the rationale of the rule remains sound. The acrobatic attempt to derive a pseudo-intellectual property or a pseudo-right of commercial exploitation of the cultural good’s notoriety in order to control (also) indirect reproduction or copying of copying (as mentioned above, the reproduction of an image published on Wikipedia) has no solid foundation either in positive law or in the policy of law.

If the right to the image of cultural property were to become entrenched in our legal system, it would result in an undue restriction of the public domain of humanity and the knowledge commons, a distancing of our country from the planetary movement promoting open access to culture, and unnecessary background interpretive noise harbinger of transactional, administrative and jurisdictional costs. Not to mention the fact that the compatibility of this right with the international (with reference to the right to culture and the right to science) and European (with reference to policies related to open science, copyright and open public sector data) regulatory frameworks remains quite doubtful.

All that remains is to hope. There may well be a judge in Berlin -- pardon me, Rome, Luxembourg and Strasbourg.

1 On the Ravensburger and GQ cases see R. Caso, The David, the Vitruvian Man and the right to the image of cultural property: towards an evaporation of the public domain?, in Foro it., 2023, I, 2283.

2 For further discussion see. Manacorda D., M. Modolo (eds.), The Images of Cultural Heritage.

A shared heritage?, Pacini Editore, 2023; G. Resta, The image of public cultural property: a new form of ownership?, ibid., 73.

3 On Ministerial Decree 161 of 2023 see the contributions collected in No. 3 of 2023 of the journal Aedon:<https://aedon.mulino.it/archivio/2023/2/index223.htm>.

This contribution was originally published in No. 20 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.