Jimmy Carter, 39th president of the United States, passed away on December 29, 2024 at the age of 100. His extraordinary life was marked not only by a relevant political career (president of the US from 1977 to 1981, Nobel Peace Prize in 2002), but also by a deep and enduring commitment to the arts, culture and music. Regarded as something of a renaissance man (diplomat Stuart E. Eizenstat, who was his chief domestic policy adviser at the time Carter was president, called him “the closest person to a renaissance man we have ever had in the White House in modern times”), Carter recognized the value of the arts as a fundamental pillar of society and human well-being.

And in this respect, Carter was certainly an out-of-the-box president, able to combine his passion for politics with a genuine love of culture. His dedication to the arts was not merely a fringe interest, but an integral part of his worldview. He believed that the arts could inspire positive change, educate people and build stronger communities. This belief made him a beloved figure not only as a politician but also as a patron of the arts. Even in his later years, Carter remained active, painting, writing poetry and participating in cultural events. He continued to support young artists and promote culture as a means to meet the challenges of the modern world.

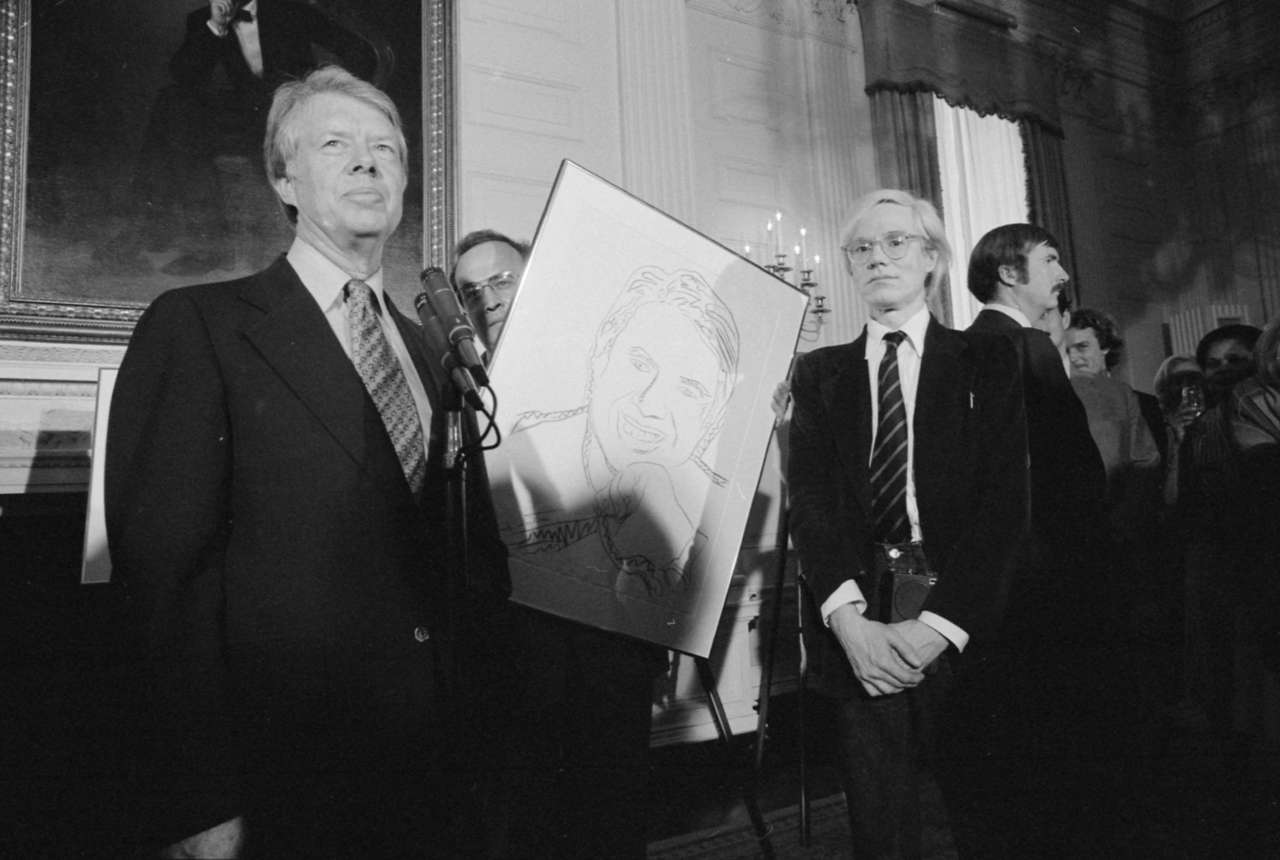

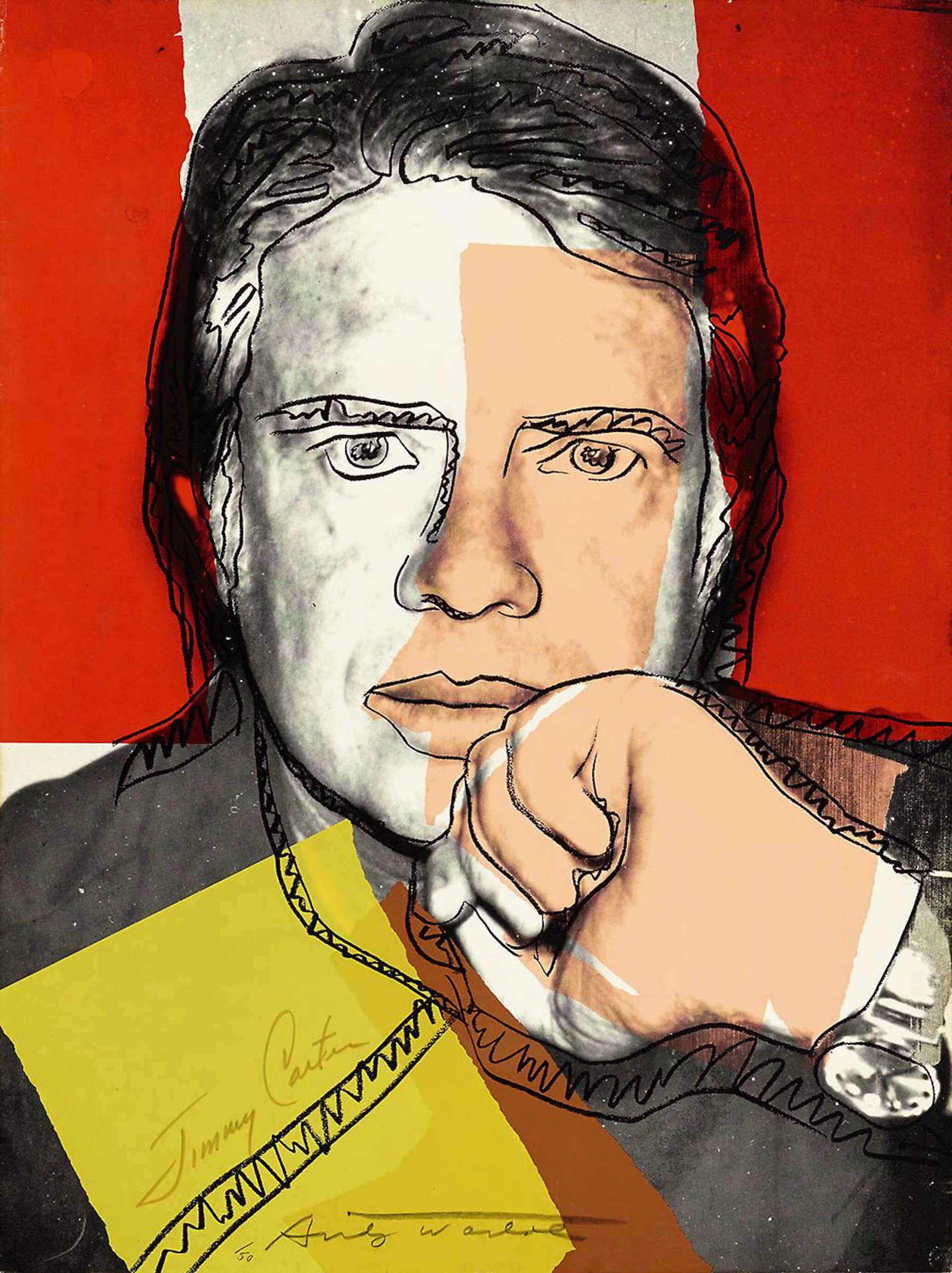

A distinctive aspect of the Carter presidency has been his commitment to the visual arts andmodern architecture. It was an interest Carter cultivated even earlier, so much so that in 1977 his campaign was supported by artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Jamie Wyeth, Jacob Lawrence, and several others. Andy Warhol, for example, was commissioned by the Democratic National Committee to design a portrait for Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign: the future president hoped to reach out to younger voters and New York City voters, thereby exploiting Warhol’s status as a pop culture icon to his advantage. This strategic move by Carter’s was aimed at positioning himself as a progressive candidate: a famous portrait resulted.

In 1978, he opened the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the wing designed by world-renowned architect I.M. Pei. Under his administration, Carter promoted arts-related educational programs and worked to expand access to culture across the country. He firmly believed that the arts could unite people, overcoming social, economic and political barriers. Carter was also one of the first politicians to work for the return of works of art stolen during conflicts: famous was the case of the Crown of St. Stephen, an 11th-century work of goldsmithing handed over in 1945 by the Hungarians to the U.S. military to prevent it from falling into the hands of Soviet forces. Carter decided to return it as a reward for Hungary’s human rights efforts, a decision that raised some controversy (Hungary was still in the Soviet orbit), but history proved that the president had seen through it.

After leaving the White House in 1981, Carter continued to influence the American cultural landscape. He wrote numerous books, many of them audiobooks that earned him three Grammy Awards. In 2025, he will receive a posthumous nomination for his work “Last Sundays in Plains: A Centennial Celebration,” a tribute to his hometown and the community he has always considered his true home.

In addition to his literary output, Carter has supported countless cultural initiatives through the Carter Center, an organization dedicated to promoting human rights and conflict resolution. He also participated in public events and collaborated with artists and musicians to raise awareness of issues such as social justice and peace.

It has gone down in history that Carter uttered that very phrase during the opening of the National Gallery’s East Wing (the entire speech can be read online). Carter, stressing the importance of government support for the arts, positively hailed the absence of a ministry of culture in the United States (which, in fact, does not have a ministry of culture): a seemingly paradoxical observation, but actually in line with his vision of the arts.

“Just as the Capitol symbolizes our faith in political democracy and civil liberty, the National Gallery symbolizes our faith in freedom and the genius of the human mind manifested in art,” he had begun. “In an open society like ours, the relationship between government and the arts must necessarily be delicate. We don’t have a ministry of culture in this country, and I hope we never will. We have no official arts in this country, and I pray there never will be. No matter how democratic a government may be, no matter how responsive to the wishes of its people: it can never be the government’s job to define exactly what is good, true or beautiful. Instead, government must limit itself to nurturing the soil in which art and the love of art can grow. So within those limits, there is much that government can do, and much that we are doing.” In Carter’s vision, a ministry of culture would eventually direct a country’s creative output: however, a government that does not support the arts is a government that does not understand the value of human creativity. The government’s role in culture, according to Carter, should therefore be to facilitate cultural growth without imposition.

In the same speech, Carter reiterated that support for the arts and humanities comes through many different channels, leaving room for the natural development of art and research: the example was precisely that of the National Gallery, which is maintained with public money but owes its existence to acts of private philanthropy.

One of the most notorious aspects of his presidency was his connection to American music and musicians, so much so that Carter was even called “the rock ’n’ roll president” (so was the title of a documentary released in 2020, Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President by Mary Wharton, devoted precisely to Carter’s relationship with rock), Carter was a huge fan of rock and country music, and his closeness to bands and artists such as the Allman Brothers Band, the Marshall Tucker Band, Charlie Daniels, and Willie Nelson was crucial to his 1976 campaign. The Allman Brothers, in particular, played a key role, organizing concerts to raise funds and mobilize young voters. This musical support enabled Carter to present himself as a progressive candidate, close to popular culture and able to inspire a new generation of Americans.

During his presidency, Carter continued to cultivate relationships with the music world, often inviting artists to the White House and participating in cultural events. His friendship with Willie Nelson, for example, has become legendary, with colorful tales even including episodes of Nelson smoking marijuana on the White House rooftop. These anecdotes underscore the approachable and humane nature of Carter, who always sought to build bridges between politics and culture. And the beauty of it all, wrote David Browne in Rolling Stone recalling Carter’s own relationship with rock, “is that Carter didn’t pay the price for friendship with those half-junkie rockers.” Browne recalled how Carter was not the first to bring rock to the White House: other presidents before him had already called music stars as guests at the White House. But Carter took rock to another level: “at a time when rockers seemed like shady types, Carter invited to Washington the underdogs that that music represented and supported. He made it the soundtrack of the party, and more.”

|

| When Jimmy Carter said, "I hope the U.S. will never have a Ministry of Culture." |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.