Umbria, Giano municipality wants to vacate important Frigolandia cultural center

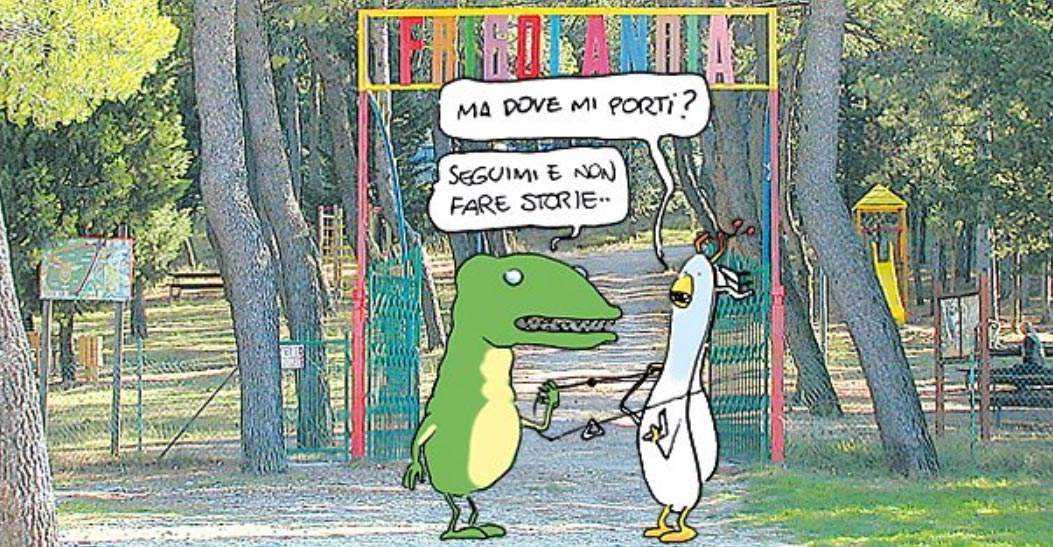

It could close after 15 years the experience of Frigolandia, the fictional city born from the mind of the great cartoonist Andrea Pazienza (San Benedetto del Tronto, 1956 - Montepulciano, 1988) and remained a dream until 2005, when in Giano dell’Umbria, a village in the province of Perugia, the municipality gave a complex of buildings in concession to a group of volunteers who brought Pazienza’s utopia to life. The complex, known as “La Colonia” (a former disused summer colony), had been granted to journalist and Vincenzo Sparagna (Naples, 1946), president of the company Frigolandia srl, famous as the founder and editor-in-chief of one of the most significant cultural magazines of Italy in the 1980s and 1990s, Frigidaire, published from 1980 to 2008: here, Sparagna founded this bizarre “Republic of Fantasy,” which fifteen years later does not cease to be a relevant artistic and journalistic experience. Now, however, an eviction order by the municipality of Giano dell’Umbria may kill Frigolandia.

But what is this unusual place? It is a cultural center that consists of a main building surrounded by several outbuildings, clinging to a hill near the Umbrian village: it is at the same time a museum (the “M.A.M. - Museum of Maivist Art,” meaning, as the original plan states, “that unforeseen, multiple, high, low, medium, pop and anti-pop art, invented, and published-from 1977 onwards-by ’certified maivist’ magazines such as Frigidaire, Cannibale, Il Male, Frìzzer, Vomito, Tempi Supplementari, Il Lunedì della Repubblica, il Nuovo Male, la Piccola Unità etc. etc.”), an archive of magazines such as Frigidaire, Il Male and the others just mentioned (and where boards of relevant illustrators such as Andrea Pazienza, Tanino Liberatore, Filippo Scozzari, Stefano Tamburini and others are preserved), a two-hectare park with areas for readings, pastimes and children’s games, the headquarters of the editorial office of Il Nuovo Male, an open-air theater, and then again a meeting place, a city and an imaginary republic, endowed with its own “Constitution,” in which, in Article 1, it presents itself as “a free union of men, women, children, animals, plants and minerals founded on imagination” and resting on solid constituent principles (“peaceful and supportive human coexistence, respect for the earth and for every living being, and the rejection of any kind of cultural, social, ethnic or religious intolerance”). Extensive descriptions of the ideas and activities Frigolandia pursues can be found on its website, www.frigolandia.eu.

Frigolandia’s archive is so important that Yale University, in 2018, acquired a portion of it to make available to its students. What’s more, this cultural center has never received any public money (on the contrary, it pays the concession fee to the municipality): it is self-financed by publishing its periodicals, organizing events, and selling “passports,” a form of support for the project that entitles you to a season ticket and 7 days to spend at Frigolandia, where there is a fully equipped cottage available to guests. An experience of important cultural value, of international level, which is therefore in danger of coming to an end. The eviction order dates back to March 11, 2020, right at the beginning of the coronavirus emergency, two days after Italy was closed for anti-contagious confinement.

But what are the reasons for the eviction? The mayor of Giano dell’Umbria, Manuel Petruccioli, elected with a civic list supported by the League after years of uninterrupted center-left administration (during which there had been other anti-Frigolandia attempts anyway) summed them up in a long Facebook post last June 10. The problem lies entirely in the 2005 concession contract, which provided, the mayor’s post reads, “an initial 10-year term expiring on 6.12.2015 and three more tacit renewals of equal annuality until, therefore, the year 2045.” In 2014, the “Colony” complex was included in the PUC-3 (“Collective Utility Project”) financed by a regional decree, and the municipality therefore “intended to regain the availability of the compendium,” but the administration at the time never proceeded to have the complex released. “With the installation of the administration that I have the honor to lead,” Petruccioli continued, “we decided to take the matter back under hand and see the legitimacy of the acts involving the controversial issue,” and with two resolutions (one in the junta and one in the council, both dated Dec. 30, 2019), the administration again expressed its willingness to regain possession of the complex. For the mayor, Frigolandia would then have violated the development obligations it was supposed to honor: “we have never seen the tourism projects,” Petruccioli wrote, “we have never seen amateurs of culture go there, we have never seen artists or even aggregations or events of thousands of people.”

It is unclear what will become of the former colony if Frigolandia is dislodged: it is likely to become a tourist complex. Sparagna tries to oppose it by asserting legal reasons (in particular the point in the contract that provided for automatic renewal until 2045: an appeal against the eviction order has been taken to the Tar) and cultural ones, the latter claimed through a petition on change. org: “Frigolandia,” Sparagna points out, siding implicitly also against the Gianesi who accuse him of doing nothing for the territory, “has been visited over the years by thousands of families, young people, scholars and researchers from all over Italy and the world, thus also multiplying the influx of tourists to the Umbrian territory.” In addition, the journalist adds, “the threat of eviction is all the more absurd since Frigolandia has never received public contributions, regularly pays the fee stipulated in the concession contract signed in 2005, and is in full activity with the publication of journals and books, the realization of study seminars, the organization of successful exhibitions and cultural events in many Italian cities.” The disappearance of Frigolandia would mean the closure of the journals as well as, Sparagna concludes, “the dispersion of the library and the precious historical archive, the subject of many Italian dissertations and specialized studies even at the prestigious Yale University in Connecticut. This would be irreparable damage and a true cultural crime.”

In support of Sparagna, a large part of the world of culture and politics has lined up. These include young journalist and cartoonist Mario Natangelo (who also had a dispute with the mayor), sociologist Uliano Conti of the University of Perugia, writer Valerio Millefoglie and, most recently, Liberi e Uguali deputy Nicola Fratoianni, who on August 5 also submitted a parliamentary question addressed to the minister of cultural heritage, Dario Franceschini, asking “what initiatives he intends to take, as far as he is competent, so that experiences of great and proven historical and cultural interest,” such as that of Frigolandia, “be protected and enhanced, including through the identification of public spaces, preventing unique heritages such as Frigolandia from being dispersed.” The battle thus seems to have just begun.

|

| Umbria, Giano municipality wants to vacate important Frigolandia cultural center |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.