There is an estate of 6,000 documents on Modigliani, but it is not known whose they are: perhaps the state's

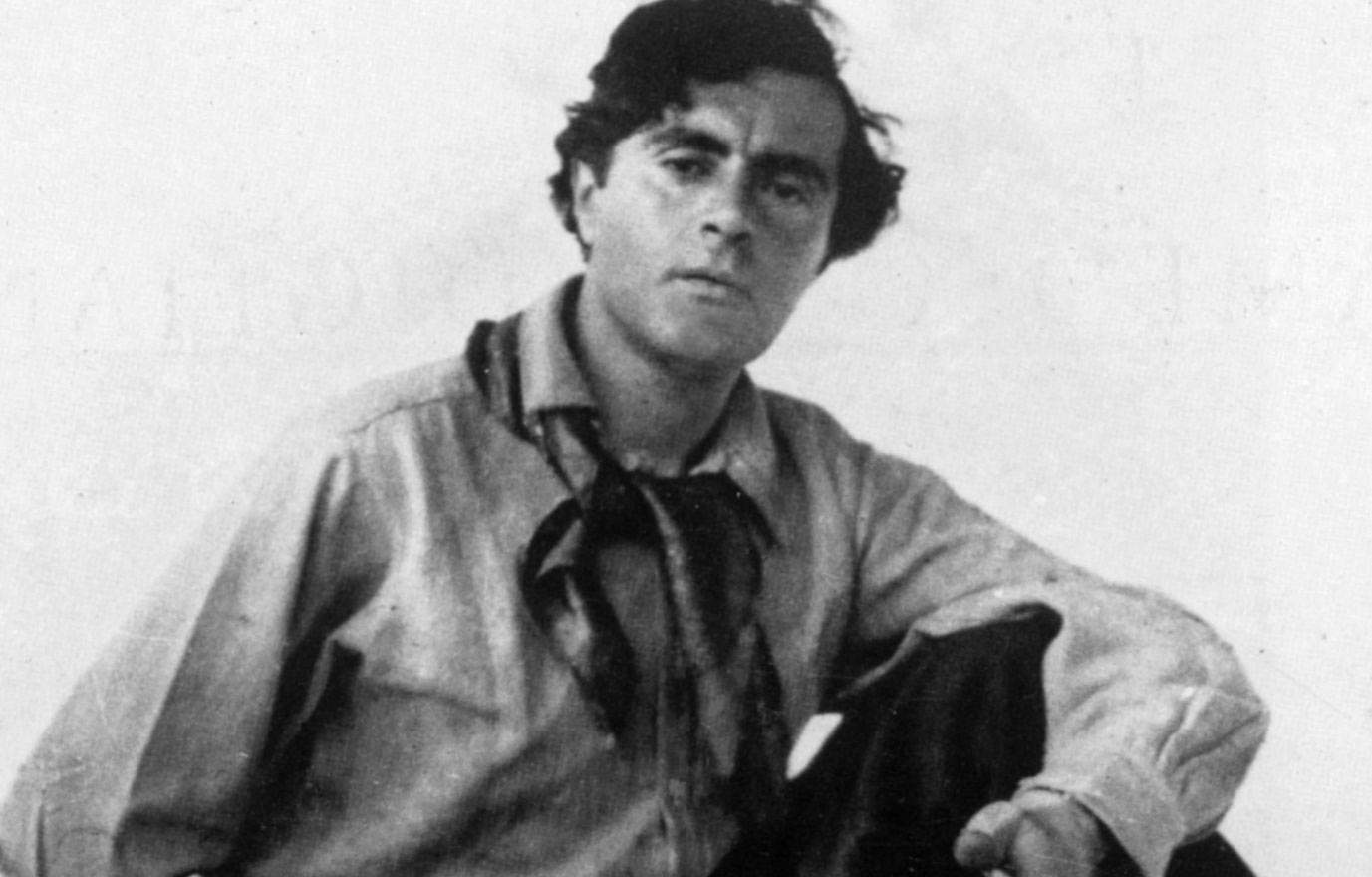

There is a treasure trove consisting of 6,000 objects by Amedeo Modigliani (Leghorn, 1884 - Paris, 1920), but it is not known to whom it belongs: these are documents, letters, artifacts, and photographs about which there is clarity regarding ownership. I 6.000 objects make up the Modigliani Legal Archives fund, and the case on their ownership has was brought to Parliament by 5 Star Movement Senator Margherita Corrado, who through a question signed by other parliamentarians of the party (Nicola Morra, Fabrizio Trentacoste, Michela Montevecchi, Emma Pavanelli, Luisa Angrisani and Maria Domenica Castellone) asks the Ministry of Cultural Heritage to take the lead in an investigation that will shed light on this extraordinary repertoire, which journalist Dania Mondini and sociologist and former police inspector Claudio Loiodice (authors of the bestseller The Modigliani Affair, a book-investigation on everything revolving around the great Leghorn painter) consider “milestone” and “keystone” to the “uncontrolled flow of interests” surrounding the painter.

The Legal Archives, Mondini and Loiodice explain in the book, were put together by Amedeo Modigliani and Jeanne Hébuterne’s daughter, Jeanne Modigliani (Nice, 1918 - Paris, 1984), and “represent,” they read in The Modigliani Affair, “the basis for making certifications on the authenticity of works attributed to Modigliani. Whoever controls them controls a million-dollar deal.” The Archives contain, among other things, the correspondence between the painter and his mother, letters that the dealer Léopold Zborowski exchanged with Amedeo’s brother Emanuele, and even rare correspondences testifying to the bond between the artist and Jeanne Hébuterne (including the marriage pledge), as well as certificates marking Amedeo Modigliani’s life.

The story of the Legal Archives is partly reconstructed in the book. Gathered by Jeanne Modigliani after decades of cataloguing in an attempt to reconstruct her father’s artistic journey, they represent a heritage of exceptional value because Modigliani left no deposited signatures, nor a list with descriptions of the works he created: the archives thus represent, Mondini and Loiodice write, “an attempt to crystallize everything that can give a certain identity to Modì’s artistic legacy.” Those who possess them, the book’s authors explain, “have in their hands the tools to make expertise and thus decree whether a work is true or false, or at least whether a given painting carries a historicity.” And since forgeries have been flourishing around Modigliani for a long time, having possession of the Legal Archives could be the watershed for re-establishing historical truth.

Based on Mondini and Loiodice’s reconstruction, in 1982 Jeanne Modigliani allegedly transferred the rights to the Legal Archives to archivist Christian Parisot (the two authors use the conditional because the authenticity of the document, a private writing, by which the transfer took place is questioned in the book: a document, the two point out, “fabricated in house, approximate, lacking legal citations and any notarial stamps, and above all without an indication of the competent forum for any disputes”). In 2015, Parisot would then transfer ownership of the Archives to art dealer Maria Stellina Marescalchi, who allegedly shelled out 280,000 euros to obtain it, in a transaction that Mondini and Loiodice say was illegal because no one would issue an invoice for the goods kept in Italy or for the earnings received.

There would be more, however: according to the two authors of the book, to claim ownership of the Archives there would also be theModigliani Institute in Rome, with which, according to the reconstruction, Parisot would have agreed on the transfer of the Archives, through “an agreement that was later disregarded” (therefore, the Institute “contends that Parisot did not respect a pact he himself signed, which provided for the transfer of ownership of the Archives to the Institute.” if this were true, Mondini and Loiodice point out, “while he was dealing with Marescalchi, perhaps the archivist was no longer even the legitimate owner of the Archives”). And in fact part of the Archives, in 2006, had been transferred from Paris (where it was located) to Rome, the headquarters of the Modigliani Institute founded the year before: all with an official ceremony (with the involvement of the highest institutional offices) at the cloister of the Sapienza, the headquarters of the State Archives of Rome.

The affair is further complicated by the fact that in 2020, as Margherita Corrado points out in her parliamentary question, the General Directorate for Archives (DGA) of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism forwarded to Corrado herself several documents, including a photocopy of the letter dated May 8, 2008, in which the Modigliani Institute informed the former Archival Superintendence of Latium of the transfer in favor of the latter, by Laure Modigliani (daughter of Jeanne, who passed away in 1984, and therefore heir to the Archives), and Cristian Parisot, of about 6.000 artifacts, including documents and objects, belonging to or related to Modigliani. Therefore, according to Corrado, as of May 8, 2008, the Modigliani Legal Archives would have become the property of the Italian state: however, Corrado points out, “there is no trace, in the transmitted deeds, either of the simple donation agreement required in the case of transfer of movable property of modest value (ex art. 783 of the Civil Code) nor of the public deed (with the relevant list of pieces and indication of value) required, on the other hand, in the case of the donation of valuable movable property, nor of the minutes of acceptance and taking over by the Ministry, indispensable in both cases.”

In confirmation of the alleged transfer to the state, Corrado cites the various requests for authorization, forwarded by the Modigliani Institute to the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, for the temporary loan of some of the materials in order to carry out exhibitions and displays abroad. “The Ministry,” Corrado writes, “did not shy away”: an instance is cited, for example, of a loan application dated Feb. 22, 2011, for an exhibition in Taiwan, with authorization granted by the DGA on March 15, 2011, after consultation with the Archival Superintendence of Lazio. The loan of the materials was then extended for other exhibitions.

However, Corrado also notes a contradiction in a response sent on June 3, 2019 by the Soprintendenza archivistica e bibliografica del Lazio to a request for information from Dania Mondini: “the Modigliani Archive,” this document reads, “was not donated to the Italian State, contrary to the intentions manifested at the ceremony in Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza on November 14, 2006, by both the heir Laure Modigliani and the then director general of archives Maurizio Fallace,” adding that “the asset does not belong to the Italian State and is not a public asset. Nor is it a private cultural asset, so the owners have no duty to the state.” The last passage is the complaint filed with the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Asti by Mondini and Loiodice: in the complaint, the two “represent the facts contained in the book about the (probably illegal) exportation of the Modigliani Archives from Italy to foreign countries, following its traces and reconstructing its path from our country to Chiasso, from Chiasso to Milan, from Milan to New York and then again from the U.S. to Geneva,” the latter city where the material would be found.

Corrado therefore asks Cultural Heritage Minister Dario Franceschini to launch an official investigation to finally clarify the terms and responsibilities of the “phantom” transfer and the reasons for the failure to declare it of cultural interest as well as the failure to affix a historical-relational bond; in addition, it is asked whether the minister does not “consider it necessary to clarify definitively that the set of about 6.000 artifacts constituting the memory of one of the greatest Italian artists of all time has a historical character and is of national interest, a reason to intervene in the most appropriate fora, Italian and foreign, so that the swift recovery of the Modigliani Legal Archives be taken care of, wherever in the world they may be, and to prosecute whoever is responsible for their removal from the State,” and sen on believes it appropriate “na once said material has returned to our country (and the sorting has been carried out to extrapolate any forgeries whose presence Mondini and Loiodice suspect), to allow the Municipality of Livorno, the city birthplace of the Master, to keep and exhibit them, so as to remove them from the speculation of private individuals who still try to use Modigliani’s name and work for illicit purposes.” Having ownership of this fundamental repertoire of documents would in fact mean beginning to shed light on Modigliani’s activity, which in recent years has unfortunately been overshadowed by many shadows as it was often the subject of interests that were anything but transparent.

|

| There is an estate of 6,000 documents on Modigliani, but it is not known whose they are: perhaps the state's |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.