The very heavy environmental costs of Crypto Art.

As interest in Crypto Art and NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens: for short, “certificates” that authenticate digital works and include information about the author, owner, transactions, and so on) grows around the world, so do concerns about theenormous environmental cost of this art form. NFTs are in fact produced through blockchain technology: it is a kind of platform-database that creates the tokens (one can imagine them as long encrypted codes that contain information about the work) and authenticates them. The problem, however, is that “minting,” or the creation of an NFT, comes at the end of a process known as proof-of-work that makes use of machines with high computing power that emit large amounts of Co2. The process to validate the works (and transactions) relies on solving very complex equations that require high computational power, which in turn requires a large expenditure of electricity. And although many of the computers that serve blockchains are powered by renewable energy, the vast majority turn out to be powered by fossil energy instead.

The most comprehensive study of the environmental impact of NFTs (whose desirability to collectors lies in their uniqueness: they are, in essence, virtual collectibles) has been carried out by Memo Akten, a Turkish-born British artist and engineer born in 1975 (real name Memet Akten) who, as of September 2020, analyzed about 80,000 transactions related to 18,000 NFTs traded on the SuperRare marketplace and created on different platforms. For one of the latter, Ethereum (one of the best-known and most widely used blockchains in the Crypto Art world), Memo Akten has, meanwhile, calculated that a single transaction costs on average, in terms of electricity consumption, about 35 kWh, the equivalent of the cost of electricity that a single European citizen consumes over four days. In practice, a single click of a mouse (what it takes to complete the transaction) produces 20 kilograms of Co2, caused by the amount of energy required to authenticate the transaction: in comparison, writes Memo Akten, watching an hour of video on Netflix produces 36 grams of Co2. It follows that a single transaction on Ethereum has an environmental impact thousands of times greater than the normal activities anyone does on the Internet.

Returning instead to SuperRare, in this case the costs are even higher, since we are talking about single transactions that cost an average of 82 kWh, emitting 48 kg of Co2. However, a single NFT can generate several transactions that can be classified as “transactions”-ranging from minting to bidding when an NFT is auctioned, to transfers of ownership. Analyzing the individual components of the process, Memo Akten’s study calculates that minting costs 142 kWh (83 kilograms of Co2, practically the consumption of about two weeks of electricity of a single European citizen), bidding on a marketplace costs 41 kWh (24 kilograms of Co2), clearing a bid 12 kWh (7 kilograms of Co2), a sale costs 87 kWh (51 kilograms of Co2), and a transfer of ownership costs 52 kWh (30 kilograms of Co2). Overall, the analysis of the approximately 18,000 NFTs analyzed by Memo Akten led to the conclusion that, in all, a single NFT has a carbon footprint of about 340 kWh which corresponds to the emission of 211 kg of Co2. To give an idea, that’s the equivalent of a European citizen’s electricity consumption for one month, the use of a laptop computer for three years, a 1,000-kilometer car trip, or a flight from Rome to London.

Of course, writes Memo Akten, an artist does not put a single NFT up for sale, consequently the impact of an artist’s average presence on SuperRare was also calculated, which is equivalent to 10 MWh and 6 tons of Co2 emissions for an average activity of 11 months (the equivalent of a European citizen’s electricity consumption over 3 years, the use of a laptop for 83 years, a total of 57 hours in the air, or 30,000 km by car).

The data can be multiplied if an NFT is sold in editions, which we can imagine as the multiples of a print edition. Memo Akten studied the case of an artist who on the NiftyGateway platform sold 800 multiples in less than three months, producing 86 tons of Co2, which is equivalent to 100 transoceanic flights and the electricity consumption of a European citizen over a 40-year period. And, Memo Akten points out, it was not the one that sold the most (and therefore consumed the most). These operations are sustained not only by the sums that collectors pay to get the works, but also by the fees that artists pay each time they want one of their works “tokenized” (amounts can reach several hundred dollars). Moreover, the distribution of sales proceeds is highly inequitable, with Memo Akten calculating that 20 percent of artists earn 75 percent of sales, with as few as 0.1 percent earning 8 percent and 1 percent earning 21 percent. As a result, SuperRare’s Palm Ratio (PR) (PR is an index that measures the inequity of income distribution) reaches a very high value, 29 (to get an idea, the country with the world’s worst income distribution, South Africa, has a PR of 7.1).

Many accuse platforms like SuperRare and NiftyGateway of being very opaque about their energy consumption (many artists, argues Memo Akten, are totally unaware of the ecological cost of transactions). And the same goes for collectors. “If you buy a work of art, you don’t see the calculations behind it,” financial analyst Alex de Vries told Time. “You don’t see that your money is going to a miner who pays for fossil energy. That’s the real problem.” Ethereum’s developers, Time again points out, have promised to launch, in 2022, a system that will use far less energy. The problem, however, the magazine explains, is that these are decentralized platforms and not subject to the control of bodies such as governments or central banks, so they cannot be forced to use more efficient systems. “It’s pretty safe,” De Vries concludes, “that miners will continue to run Ethereum in the current way,” given the large turnover. And the bad news is that, according to some analysts, the success and wave of enthusiasm for NFTs could give rise to other energy-intensive platforms. Calls for a more ethical Crypto Art are already springing up, then: just ten days ago, for example, the Cryptoart.wtf website was born, which aims to work to bring down the ecological costs of this market.

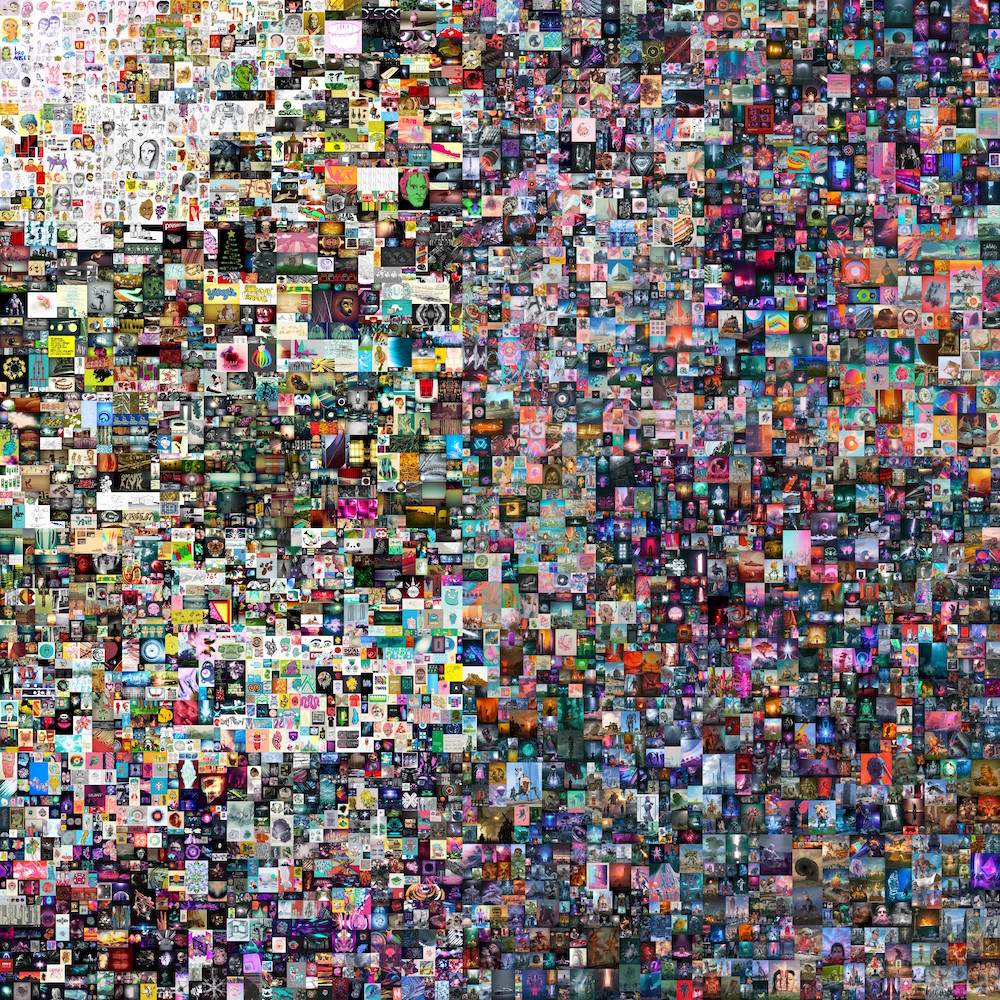

Image: Beeple, Everydays The First 5000 Days (2007-20021; JPG file, 21,069 x 21,069 pixels)

|

| The very heavy environmental costs of Crypto Art. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.