London, Easter Island delegation asks British Museum for the return of a moaï

In London, a delegation arriving fromEaster Island, the Pacific Ocean island administratively part of Chile and world-famous for its statues of stone giants, asked the British Museum for the return of Hoa Hakananai’a (“hidden friend,” in the local language), a moaï (i.e., one of the celebrated stone statues) removed by the British in 1868 (without any permission), at the time of colonial rule (specifically, the monument was stolen from the British frigate HMS Topaze by Captain Richard Powell, and then donated to Queen Victoria. Today, the monument is kept in the British Institute. The request came as part of a meeting of the delegation from Rapa Nui (this is the name of Easter Island in the local language), in the presence of the Chilean minister of culture, Felipe Ward, with the British Museum’s management.

The Guardian newspaper reports that the request took place in rather heartfelt tones: the governor of Easter Island, Tarita Alarcón Rapu, the pages of the English newspaper read, reportedly “tearfully begged” (i.e., “tearfully pleaded”) with the management to agree to Hoa Hakananai’a return home. “My mother, who passed away at almost ninety years old,” said the governor, “never had the opportunity to see her ancestor. I myself am almost fifty years old and this is my first time.” The moaï, in fact, are believed to be the ancestors of today’s islanders, and these statues represent the soul of Rapa Nui. “I believe that my children, and my children’s children,” Rapu added, “deserve the opportunity to touch, to see the statue, and to learn from it.” Without the statue, “we have only a body, and you, the British people, have our soul.”

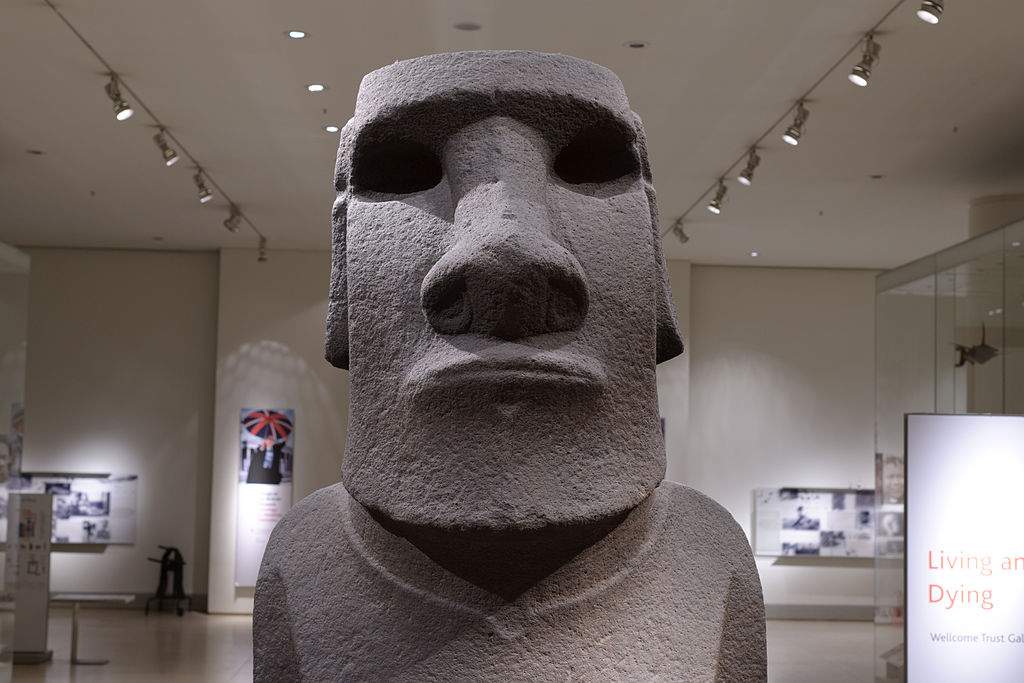

The British Museum’s moaï, standing 2.4 meters tall and weighing 4 tons, has been kept in the halls of the London institution for one hundred and fifty years, from the time of its arrival: after receiving it, Queen Victoria decided to make a gift of it to the British. It is, moreover, a specimen of great value, because on its surface is carved an unusual element: some bas-relief figures describing religious cults of the islanders, such as that of the bird-man who, according to the Rapa Nui creed, would bring peace to the island after a period of wars. It is believed to have been carved around 1200, and several historians even consider it the finest moaï we know of.

A spokesperson for the British Museum reported that the discussion with the Rapa Nui delegation was “friendly and warm,” and provided a better understanding of Hoa Hakananai’a’s importance to the islanders. At the moment, however, the institute’s intentions have not yet been made explicit.

Pictured: Hoa Hakananai’a (c. 1200; stone, 242 x 96 x 47 cm; London, British Museum). Ph. Credit James Miles

|

| London, Easter Island delegation asks British Museum for the return of a moaï |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.