In Lille, northern France, the demolition of the chapelle Saint-Joseph, a neo-Gothic style church built in 1886 in the Vauban quaritere, designed by architect Auguste Mourcou (Lille, 1823 - 1911), began a few days ago. The building had long been abandoned: the church had been deconsecrated, and on May 28, 2019, a demolition permit was obtained to build, in place of the chapelle, part of the new Junia campus, a private school of engineering studies. The project involves the construction of a 40,000-square-meter space, of which 22,000 will be new and the remainder from renovations, for a 128-million-euro investment: the school will have to accommodate between 5,000 and 8,000 students, and some spaces will be built right where the church being demolished now stands.

The demolition of the chapelle Saint-Joseph has been discussed for two years, and a vast mobilization of the cultural world had been created in France to save it: a request had even been made for a cultural interest restriction, which, however, the Ministry of Culture refused because, it explained in a November 2020 statement, the patrimonial interest of the chapel was not considered sufficient to justify the attachment. The ministry had then spoken of a “very degraded state,” although this information had been denied by architect Étienne Poncelet, former inspector of historic monuments, according to whom the chapel could be safely restored to a normal state of stability. The church, moreover, was part of a unified architectural complex, that of the Collège Saint-Paul, of which the main body, Palais Rameau, designed by the same architect and classified as a historic monument, will be restored: the destruction of the unity of a complex is therefore contested.

Hard objections were also made against the other reasons given by the ministry, namely the disinterest into which the chapel had fallen and the need not to abandon “an important project for the development of higher education” (and for which the destruction of the chapel was evidently necessary): two reasons that obviously cannot provide the basis for demolishing a 19th-century church. Appeals to the two ministers of culture (first Franck Riester, then Roselyne Bachelot) to save Saint-Joseph had also recoiled. One of the most important initiatives was, in January, the letter from the “G7 Patrimoine,” the union of seven heritage associations (Maisons Paysannes de France, Patrimoine-Environnement, Sites & Monuments, Demeure Historique, REMPART, Sauvegarde de l’Art Français, and VMF), who wrote to Minister Bachelot pointing out the importance of the chapelle Saint-Joseph, and asking that at the very least a concertation be organized that would allow Saint-Joseph to be included within the school expansion project: “it is not only a question of saving an element of Lille’s heritage,” the letter’s signatories explained, “but also of integrating it into a project for the future that enhances its roots instead of destroying them.” At the same time, the NGO Urgences Patrimoine had also moved, asking for at least a postponement. But it was all to no avail.

Against the demolition the ire of the world of culture was unleashed. The stance of Stéphane Bern, a very popular television host of programs devoted to art and history and very active in the field of preservation, was very harsh, writing on Twitter, “Enough with the demolitionists and heritage sinkers. One day you will have to answer for your actions, legal but unjust!” Urgences Patrimoine, with an op-ed in its organ La Gazette du Patrimoine, asks instead what message is being imparted to young people.

Journalist Didier Rykner, editor of the newspaper La Tribune de l’Art, which has from the outset initiated a combative campaign against the demolition of the chapelle Saint-Joseph, wrote that “the names of those responsible for this act must be indicated. Of course, the owners of the chapel, the Junia school and the Université Catholique de Lille, who are at the origin of this destruction, are guilty. But much less so than those who should, for the good of the community, protect our heritage from such destruction. Those who have all the weapons to prevent the scorpion from striking are more guilty than the little beast, whose purpose is to strike and who has no consciousness of its actions. In France there is a law to prevent such things. It would be necessary for those in power to want to apply it.” Rykner lists one by one the names of those who he believes should have prevented the demolition but did not: Catherline Bourlet (head of the Unité départementale de l’architecture et du patrimoine), Martine Aubry (mayor of Lille), Philippe Barbat (director general of Heritage and Architecture), and even Culture Minister Roselyne Bachelot (her predecessor Franck Riester had called for a postponement instead). “The Ministry of Culture,” Rykner bitterly concludes, “has the role of protecting heritage, but it often drowns it.”

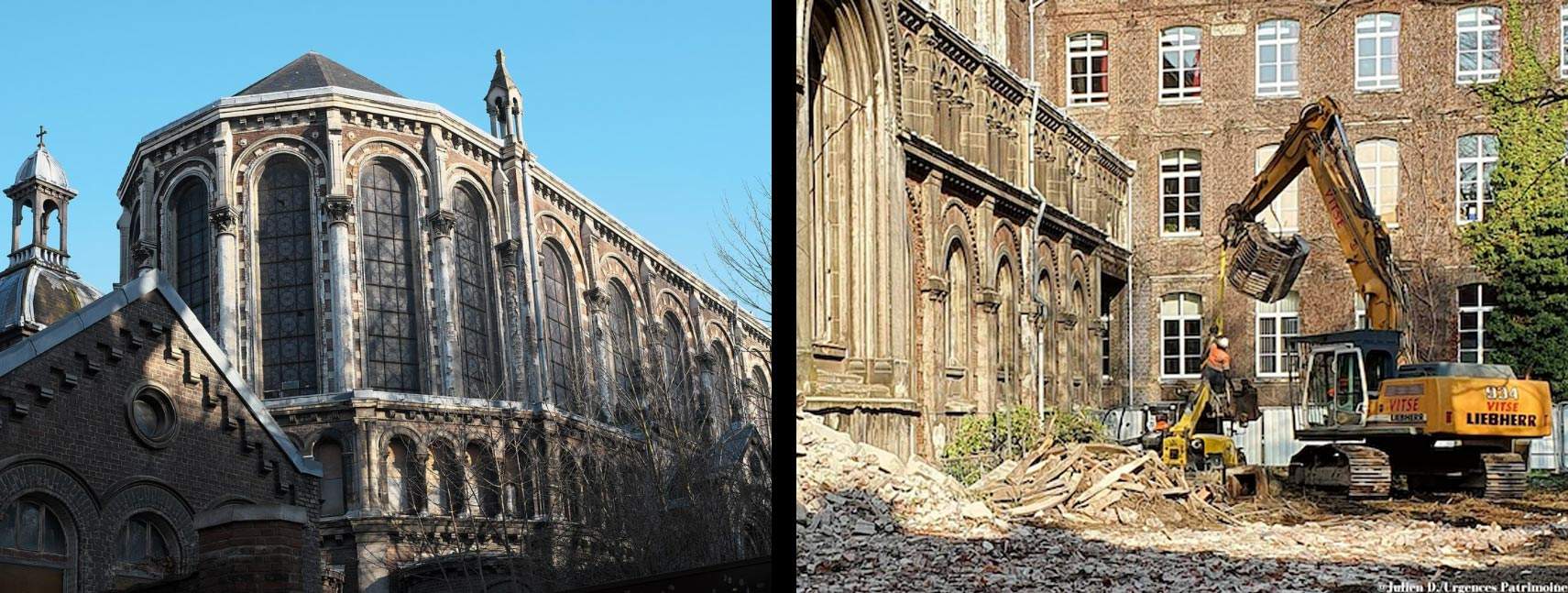

Image: left, the chapelle Saint-Joseph still standing (photo G. Freihalter). On the right, the ongoing demolition (photo Julien D. / Urgences Patrimoine).

|

| France, a 19th century church is being torn down in Lille. The ire of the cultural world |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.