Florence, restorations at San Miniato al Monte end after one year

Restoration work in the church of San Miniato al Monte in Florence has been completed, made possible by a donation from Friends of Florence, the American foundation that has been supporting the conservation of the Florentine and Tuscan heritage since 1998, thanks to its donors from all over the world who daily care about the future of these masterpieces. The intervention was carried out under the High Supervision of the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the Metropolitan City of Florence and the Provinces of Pistoia and Prato, by a team of restorers and professionals in diagnostics and conservation.

The restoration involved several parts of the Abbey: theapse with its marbles and the mosaic in the basin, thealtar and the Christ Crucified in glazed terracotta, the Pulpit and the Transenna, and the Reliquary Bust of San Miniato, the latter winner of the 5th edition of the Friends of Florence Art and Restoration Prize organized by the Foundation in collaboration with the Salone of the same name.

Prior to the restoration, the works were in different states of preservation: while the pulpit and transenna (the latter with the wall paintings on the back), although in fair condition, were covered by consistent and inconsistent deposits, the altar showed rather extensive alteration at the string-course cornice, the arches and the wainscoting that rests on the marble seat. The Christ Crucified, in addition to a high layer of atmospheric deposition, had old pictorial additions on the loincloth and arms and had one hand totally detached and supported by nails. The mosaic of the apsidal basin, which was also covered with inconsistent and coherent deposits due to dust, atmospheric deposits, and black smoke that had dulled it, was affected by both structural problems such as lesions and plaster adhesion defects, and superficial problems such as lifting of individual tesserae and more superficial layers of the mosaic. The decoration in some areas was very disordereddue to numerous altered and overflowing plasterwork and extensive repainting. Finally, the reliquary bust was also in a compromised state of preservation, both in terms of the constituent materials of the support - marked by some cracks - and the polychromy affected by repainting and numerous lifts in the color and gilding.

The entire work lasted about a year, including analysis of the state of conservation, study of the execution techniques of each work, testing and cleaning, plastering and retouching. The team of restorers worked in profound synergy, with full respect for the Abbey and the community of Benedictine monks who live there daily, aware that first and foremost San Miniato al Monte is a place of spirituality and that culture is and must continue to be its support and service. And it is with this in mind that the restoration of each work not only served to preserve the surfaces, but was propitious to ensure their legibility, usability and to study their technical and historical-artistic aspects.

The work was carried out under the high supervision of Maria Maugeri and Lorenzo Sbaraglio, official art historians of the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the Metropolitan City of Florence and the Provinces of Pistoia and Prato. The restoration of the transenna, pulpit, apse, and altar was carried out by Daniela Manna and Marina Vincenti with the collaboration of Laura Benucci, Vittoria Bruni, Elisabetta Giacomelli, and Simona Rindi. Restoration of the mural painting on the back of the transenna was performed by Bartolomeo Ciccone, Donato Ciccone, and Sara Chiaratti. The restoration of the apsidal basin is by Habilis S.r.l. (Andrea Vigna and Paola Viviani) with the collaboration of Stefania Franceschini, Chiaki Yamamoto, Eleonora Bonelli, Arianne Palla, Giulia Pistolesi and Marialuce Russo. The restoration of the Christ Crucified in glazed terracotta was carried out by Filippo Tattini. The restoration of the Reliquary Bust of San Miniato was performed by Anna Fulimeni with the collaboration of Francesca Rocchi.

Photographic documentation: Antonio Quattrone; Torquato Perissi for the Bust of San Miniato. Photographic documentation with UV fluorescence: Ottaviano Caruso. Scientific investigations by ISPC CNR of Florence by Donata Magrini, Barbara Salvadori, Silvia Vettori for the restorations to the transenna at the pulpit, apse and altar; by Cristiano Riminesi and Barbara Salvadori for the mosaic in the apse basin. Investigations with x-ray ELIO spectrometer for characterization and localization of the elements present by acquisition of elemental distribution maps by the Department of Earth Sciences University of Florence (Alba Santo, Sara Calandra). Petrographic investigations on color samples of the San Miniato Reliquary Bust: Marcello Spampinato. Diagnostic investigations on the San Miniato Reliquary Bust: CT c/o Fanfani Institute, Florence, Cecilia Volpe; RX, UV, IR,Teobaldo Pasquali. Laser equipment for cleaning the transenna, pulpit and apse: El.En. Group. Scaffolding: EdilCalosi S.n.c. Video shooting; Artmedia studio of Vincenzo Capalbo and Marilena Bertozzi, with the collaboration of Federico Cavallini.

Historical-artistic profile

The just-completed restorations represent the latest stage of a journey that began in 2017 with the restoration of the Chapel of the Crucifix and its furnishings, under the direction of Daniele Rapino (this is the chapel erected in 1447 to a design by Michelozzo to house the miraculous Crucifix of St. John Gualbert, transferred in 1671 to the Church of Santa Trinita and on thealtar replaced with Agnolo Gaddi’s polyptych depicting the same holy founder of the Vallombrosa Abbey). In 2019, the site moved to the Chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal erected following the young prelate’s death in 1459 to a design by Antonio Rossellino with contributions from his brother Bernardo, Luca della Robbia, the Pollaiolos and Alessio Baldovinetti. Through the delicate work of cleaning from the young cardinal’s catafalque, traces of gold that once marked the tomb’s ornaments emerged, while from the glazed terracotta of Luca della Robbia’s covering reappeared the original gold leaf applied to mission thanks to the use of laser employed here for the first time with which it was also possible to remove the now altered purple repainting.

Still open this site, our restoration project began on all the marbles of the raised presbytery area, the mosaic of the apsidal basin with the marble facing of the fascia below, the altar and its Crucifix. At the same time, the Reliquary Bust of St. Miniato attributed to Nanni di Bartolo was restored, a work that won in 2020 the bid promoted by Friends of Florence in collaboration with the organizational secretariat of the Florence Art and Restoration Fair.

Current restoration work began in the spring of 2022 on the marble transenna and ambo, which had already been dismantled in 1910 by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, to proceed with cleaning and fracture additions, unique pieces of Romanesque art extensively studied by Guido Tigler and Nicoletta Matteuzzi, who date them to between 1160 and 1175. The transenna that encloses the choir is divided into square panels bearing finely carved rosettes inside, a decoration this close to the decorative motifs of the panels of the dismembered enclosure of the baptismal font of the Florence Baptistery, now preserved in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. In its setting, the ambo repeats the one completed around 1162 by Guglielmo for Pisa Cathedral, now in Cagliari Cathedral, removed in 1310 to make way for Giovanni Pisano’s. A model, Guglielmo’s, spread throughout Tuscany: one example above all is Guglielmo’s Taglia di Guglielmo ambo for Pistoia Cathedral, with the Florentine variant where geometric decoration was preferred to figurative. The ambo of San Miniato served as an inspirational model for other examples executed in later years, among which the closest appears to be that of the Pieve di Sant’Agata in Mugello, in which is given the date of execution 1775, because of the presence of the same sculptural group, read in iconological terms by Giovanni Serafini as the celebration of the Resurrection, composed of the lion’s head resting on a shelf molded in the shape of an acanthus leaf, above which rises the human figure, a sort of telamon supporting the eagle, which in turn holds the lictor.

Of later execution is the altar, which, compared to the decoration of the transenna, the ambo and the marble facing of the apsidal basin, shows an updating of the geometric score through the insertion of two stylized amphorae on either side of the frontal mirroring.

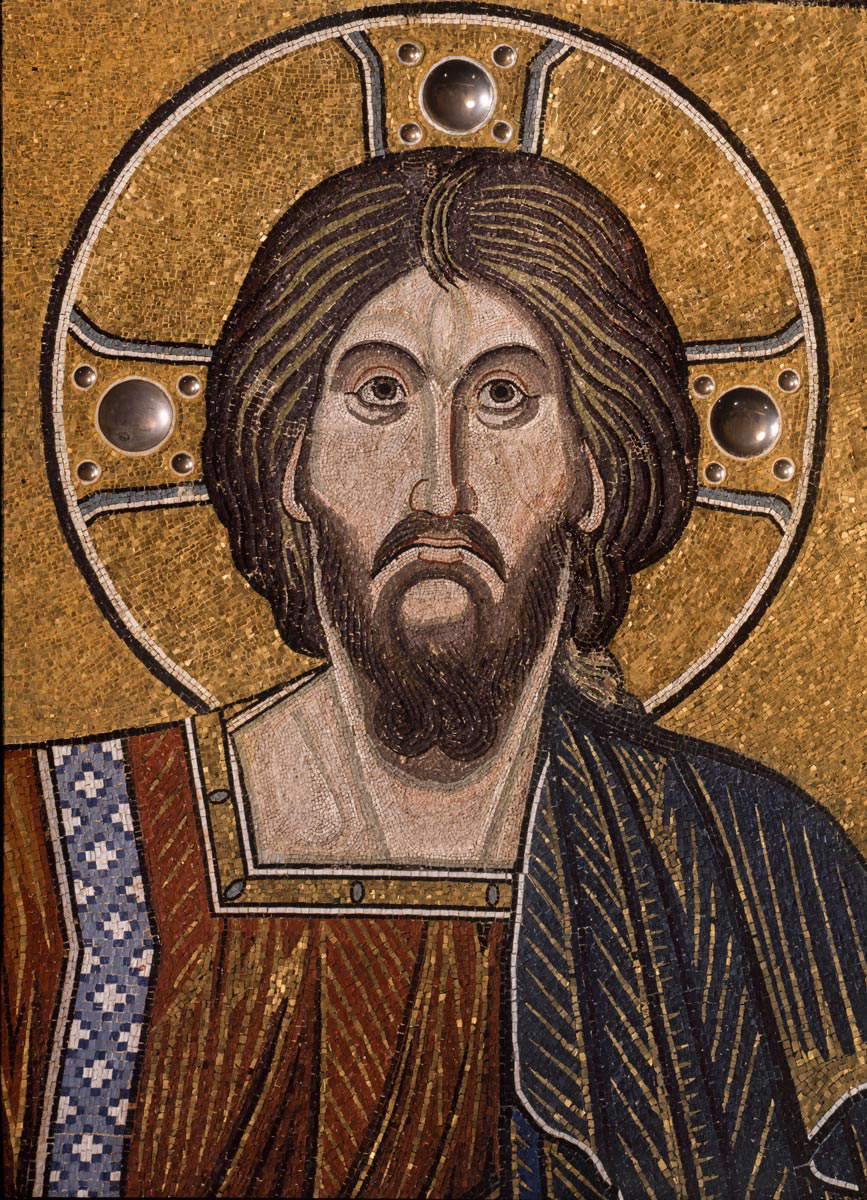

As for the mosaic of the apsidal basin, the restoration confirms what Angelo Tartuferi had already argued extensively, namely in other words that it was made in two phases, the upper band, attributed by the same scholar to the Master of St.Agatha dating it to about 1260, with Christ Pantocrator flanked on one side by Saint Miniatus who in his role as King of Armenia gives him his crown and, on the opposite side, a Madonna little legible in its originality as it was extensively remodeled by the 19th-century restoration. The lower band was updated with the symbols of the four Evangelists around 1297, the date placed in the lime in the basin and admissible although the original tiles have been partially replaced.

Prior to the current restoration, observation from below suggested the need for general cleaning to restore luster to the tesserae, but the true conservation condition became clear only after the scaffolding was erected when the detachment of so many of the original tesserae was determined. If it is difficult to circumscribe the 1491 intervention of Alessio Baldovinetti, who spent the last years of his activity in the care of the mosaics of San Miniato, more legible was the vast portion, with greater insistence on the left wall, subject to the replacement of tesserae brought directly from Venice by master glassmaker Sante Antonio Gazzetta in 1860, “equalizing it to the new, as a sign of not distinguishing from this to that,” a mirror thought of the method of the time oriented toward remakes rather than keeping the artist’s original intervention and thought comprehensible. More restrained, however, is the substitution of tiles by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in 1907. To summarize, after the past restorations, the most intact area of the entire mosaic is the right area, part of the fascia below and the decoration of the intrados of the arch, with the total remaking of some portions, including the figure of the Madonna for which it is not understandable how much and whether the original design has been tampered with.

At the planning stage we all agreed to include in the restoration project also the glazed terracotta Christ Crucified located on the high altar, formerly attributed to Luca della Robbia and rightly traced to the workshop of Benedetto Buglioni by Giancarlo Gentilini. Not a sculpture molded in the round, but rather a flattened figure with a hollowed-out back, an indication in my opinion that it is what remains of a composition placed within a demolished niche. The adaptation to an altar crucifix dates to the late 19th century, a dating suggested by the older wooden cross applied to another larger cross in 1930, when the work underwent restoration to reattach the arms to the torso.

Very complex because of too many repaintings from past undocumented restorations was the work on the Reliquary Bust of San Miniato, so mentioned in the sources, although CT scans found no object inside the sculpture, hence the inference that the relic was in the lost base, later replaced with the modern one.

The Bust, of fine workmanship, was led to the Sienese sphere by Carli, perhaps Antonio Federighi trained in 1438 in the shadow of Jacopo della Quercia on the building site of Siena Cathedral, while the name of Baccio da Montelupo is given in a note in the margin of a reproduction preserved in the photo library of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence. More convincing, however, is the attribution to Nanni di Bartolo, documented from 1419 onwards alongside Donatello in the Santa Maria del Fiore building site, comforted by the comparison between this sculpture and the Madonna and Child from the Convent of Ognissanti, on display at the major exhibition on Donatello at Palazzo Strozzi, because of the commonality of the figure’s physicality and the structure of the drapery. Crediting this attribution, the dating of the Reliquary Bust of San Miniato should fall within 1423, a date this marking Nanni’s hasty flight from Florence for debt on February 11, 1424, sheltering in Venice where he obtained prestigious commissions for the Basilica of San Marco and the Doge’s Palace.

The restorations: the transenna

The transenna, placed on the chancel to separate the space of the Heavenly Jerusalem dedicated to prayer, consists of two short and two longer sections with three entrances to access, on the left to the organ and on the right to the choir and sacristy. The transept, which has undergone maintenance and restoration over time with substantial replacement of worn or damaged portions of the moldings and cornices, is in a fair state of preservation. The restoration portions are distinguishable by a slightly lighter coloring of the materials used. Small reconstructions of decorative elements of the cornices were made of alabastrine plaster. Inconsistent and consistent deposits were found throughout the surface, especially at the corner elements of the jambs on either side of the entrances as well as on the reliefs of the decorative panels that are particularly “attractive” to visitors’ hands because of the refined and meticulous sculptural technique. In particular, within the carvings was visible a dust consisting of pinkish-colored fibers presumably a residue of an abrasive paste used in previous polishing and maintenance associated with residues of waxy substances applied in the past. Locally, black stains resulting from uneven burning were visible. Serpentine elements showed a differentiated degradation with phenomena of disintegration, spalling, dulling, and remaking plastering, associated with small-scale failures of both the vegetal decorations of the marble cornices and small portions of the inlays below the ambo. Metal elements, such as staples and pins, were present at the sides of the entrances and visible at the top of the transenna.

The restoration work was marked by the following phases: 1. Careful removal of deposits of an inconsistent nature with low and medium power vacuuming with the aid of soft bristle brushes of various sizes; 2. Mechanical removal with the aid of scalpel of traces of wax and unstable and decohesive fillers; 3. Cleaning with absorbent cotton swabs soaked in decolorized alcohol and pure acetone and subsequent removal of deposits of a more consistent nature with demineralized water. Where necessary, and locally, a 10% aqueous solution of ammonium carbonate supported by medium-thick Japanese paper with repeated rinses with demineralized water was used; 4. The most deteriorated serpentine elements were consolidated with brush-applied ethyl silicate until completely imbibed; 5. Small- and medium-sized deficiencies were supplemented with Polifilla stucco, those of depth with river sand and lime putty, those of pink marble with Verona Red marble powder, and those of serpentine with black and green marble powders aggregated by acrylic microemulsion; 6. Finally, the fillings were glazed with watercolor.

The

The The restorations

The restorations The restorations: the

The restorations: the The restorations: the

The restorations: the

The restorations: the pulpit

The pulpit rests, on the walkway side, on two breccia columns with marble capitals in composite Corinthian style, while the other rests directly on the transenna. The entablature consists of a marble cornice in continuity with that of the transenna and a serpentine molded frame. Each side of the pulpit consists of two panels with a central rose window surrounded by geometric inlays of serpentine and marble, set in marble frames. On the panes runs a frieze with serpentine and marble inlays like the cornice. On the front side of the pulpit, in the center of the two panels, a marble shelf worked with acanthus leaves supports a lion on which is placed a telamon monk with a capital supporting the eagle holding a marble lectern. All sculptures have glass paste eyes.

A fair state of preservation was found with rather extensive deposits of a coherent and inconsistent nature. The columns and capitals were particularly chromatically altered due to the presence of fatty/ waxy substances applied during past maintenance work. The delicately carved capitals suffered losses of small portions of matter with obvious wax and blackish burn residues. The pietra serena pulpit flooring bore cracks and and exfoliation in the visible part below, most likely caused by previous water infiltration. The marble and serpentine mirrors and cornices were in good condition. The sculptures bore consistent and inconsistent deposits and brown stains only at the snout of the lion.

The restoration work was punctuated by the following steps: 1. Careful removal of deposits of an incoherent nature with low and medium power vacuuming using soft bristle brushes of various sizes; 2. Use of laser equipment for removal of blackish-colored substances visible on the left capital; 3. Mechanical removal of traces of crumbling wax and grout; 4. Cleaning with absorbent cotton swabs soaked in decolorized alcohol and pure acetone and, where necessary, locally with White Spirit.

The

The The restorations: the pulpit

The restorations: the pulpit The restorations:

The restorations:

The restorations: apse and altar

The apse consists of five niches interspersed with serpentine columns with marble capitals in composite Corinthian style. All decorative elements are made of marble and serpentine. The back slabs are made of Serravezza breccia. All serpentine elements showed rather extensive alteration at the string-course cornice, arches, and plinth resting on the marble seat. The marble elements were in a fair state of preservation unlike the capitals due to the presence of a lime-based patination rather consistent with the stone substrate. There were rather extensive remakes and additions on the serpentine elements. Most likely these were polyester resins used during more recent maintenance that caused extensive abrasions on the original marble surfaces during the intervention.

After thorough dusting with vacuum cleaners and soft bristle brushes of various sizes, a series of preliminary cleaning tests were performed. The marble elements were cleaned with demineralized water and soft compact sponges after degreasing with absorbent cotton tablets soaked in decolorized alcohol and pure acetone, followed by swabs soaked in White Spirit. Only locally were medium Japanese paper veils applied to support a 10% basic solution with the intention of removing deposits of a more consistent nature. Cation exchange resins were used for partial removal of limestone encrustations on the capitals at differentiated times. The serpentine elements were cleaned with water and soft compact sponges while simultaneously consolidating the surfaces with lithium silicate applied by brush until completely imbibed, rinsing the treated areas scrupulously for any excess product. The joints between the blocks were partially integrated with Polifilla while the gaps on the serpentine were integrated with marble powders similar to the original aggregated by acrylic microemulsion. It was then decided to mask the old resin integrations with tempera, acrylic colors and watercolors according to the areas.

The altar also underwent cleaning in several stages: 1. Degreasing of the surfaces with absorbent cotton swabs soaked in decolorized alcohol and pure acetone; 2.Removal of deposits of a more consistent nature with soft compact sponges; 3.Mechanical removal with scalpel of wax drips, partial for waxy stratifications with absorbent cotton swabs soaked in White Spirit; 4.Grouting of the joints at the joints between blocks with polyphyll and subsequent masking with watercolors.

The

The The restorations: the apse

The restorations: the apse The restorations:

The restorations:

The restorations: the mosaic of the apse basin

The execution technique of the parietal mosaic is the direct technique, which involves the application of the tesserae on a plaster that is still fresh, on which a preparatory drawing has been made. Working in situ, the mosaicist connotes the scene with chiaroscuro effects through the slope, course and bedding of the tesserae. The mosaic apsidal cap has an area of about 55 square meters and expresses with its iconographic and iconological setting the didactics of the monastic communities. The San Miniato mosaic was probably made in several stages since the 1370s. One of the peculiarities of this mosaic is the execution technique that makes use of many natural and artificial stone materials and different types of glass pastes. A documented nineteenth-century restoration by Antonio Gazzetta was responsible for an impressive mosaic remake using the indirect technique, whereby the typical irregularity of the mosaic surface was lost for a very planar mosaic with regular tesserae arrangement.

The mosaic consists of lapidary, vitreous, gold-foil, ceramic and with less frequency, painted lapidary tesserae. Particularly relevant is the rendering of the faces; the tesserae here are very small in size with an irregular texture.

Given the material complexity of the San Miniato mosaic, the study and classification of the type of all the mosaic tesserae present was carried out, sorting them into descriptive tables accompanied by macro and microphotographs with metric reference. The methodical classification simplified the reconstruction of the original execution and restoration phases, facilitating the design of the restoration work.

The observation of the surfaces and the diagnostic campaign conducted by the CNR, revealed the presence of structural (lesions and plaster adhesion defects) and superficial (lifting of individual tesserae and more superficial layers of the mosaic) problems. The surface was entirely covered with inconsistent and coherent deposits due to dust, atmospheric pollutant deposits, and black smoke that had severely opacified the mosaic. The decoration appeared very disordered in some areas due to numerous altered and overflowing stuccoes that could be traced to several earlier phases. Interstitial plastering executed by means of very fluid grouting was found at the face of St. Miniatus and the neck of a cherub. The tiles that showed most advanced degradation were the white marble stone tiles, the painted white marble tiles, and the stucco tiles. The gold-leaf vitreous tiles showed typical damage related to the layered structure, with lifting and cracking of folders. Another element of degradation was the presence of extensive repainting that covered many areas of tesserae. The main color used was a deep blue that analysis identified as Prussian blue.

In order to expand the knowledge of the work and its state of preservation, a diagnostic campaign was initiated, first through non-invasive techniques (Thermography-IR, Multispectral Imaging, XRF) and later through invasive investigations (FT-IR Spectroscopy, SEM). In order to understand the structural stability of the plasters of the entire apsidal canopy, a thermographic investigation was carried out first in total and then in the areas with the greatest plaster detachment problems. The survey finally allowed the mapping of the main plaster detachments, UV fluorescence imaging first allowed the recognition of organic and inorganic materials, imaging also aided the identification of restoration interventions.To characterize the nature of some of the tiles and the different bedding mortars, which had never been studied so far, mortar and tile samples were taken.

As for the restoration work, the deposits were removed in several stages: first by soft brushes and micro-aspirators, smoke sponge, fermature with infiltration of PLM-A® hydraulic mortar and mixtures of acrylic resins in aqueous emulsion, Paraloid® B72 in a low percentage was used for the re-adhesion of the tiles. Coherent deposits were removed by ammonium bicarbonate packs in Nevek®. PLM plasters carbon pins and epoxy resin grout lime and sand etched mortar retouching with tempera paints and Laropal resin.

The

The The restorations: the mosaic of the apsidal

The restorations: the mosaic of the apsidal The restorations: the

The restorations: the The restorations: the

The restorations: the

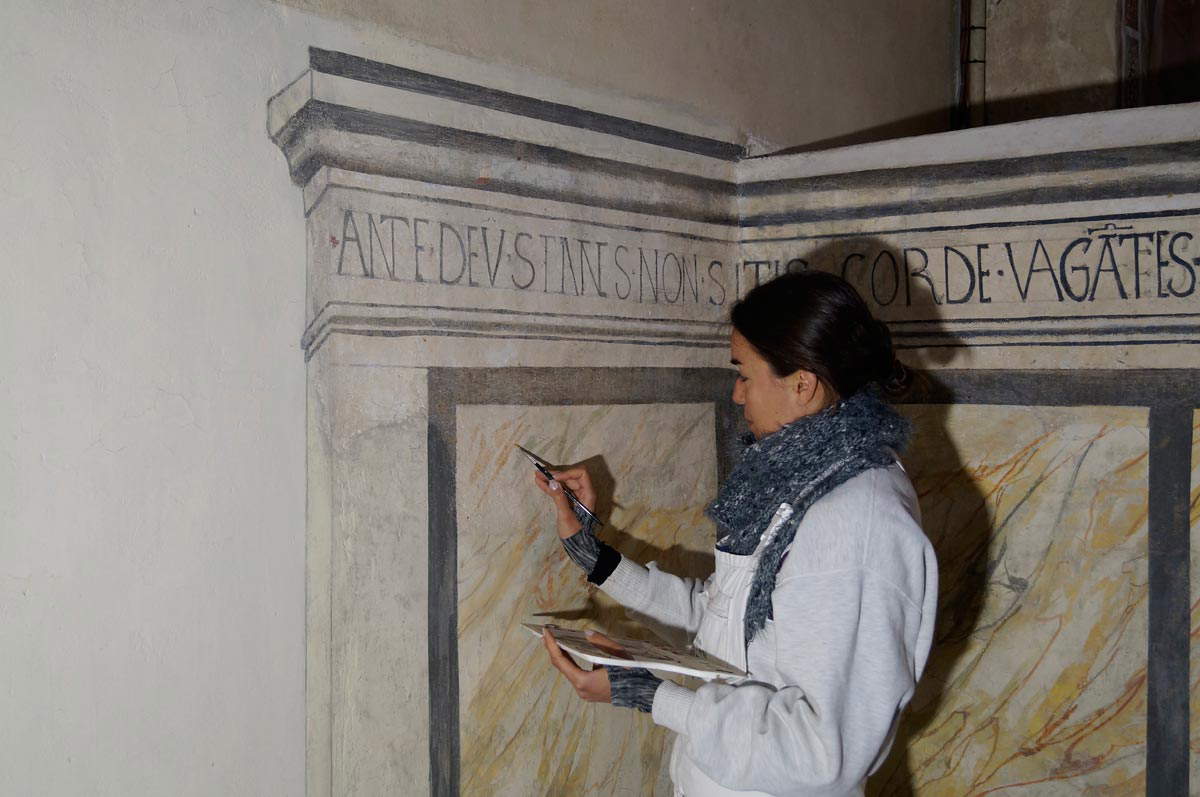

The restorations: the wall paintings and faux marbles

The wall paintings in question located at the church of San Miniato al Monte in Florence decorate the back of the right side of the marble transenna with decorative architectural elements, faux marbles, frames and inscriptions in Latin. The paintings in addition to being a decorative compendium to the already ornate and rich marble decoration served as a warning to the monks who went to pray as the Latin inscription warned them that “when you are before God do not be far from the heart because if the heart does not pray in vain the tongue works.” The paintings probably date from the earliest period of the church; we can assume execution between the 13th and 14th centuries.

With regard to the technique of execution we are faced with a lime painting on fresh plaster for the portion of the decoration adjacent to the access staircase to the pulpit, while a good fresco for the one located near the entrance to the cloister, except for the large portions of plaster remakes executed last century in lime.

The state of preservation was all in all good, except for the numerous repaintings present and some plaster detachments about to fall off. The pictorial film was in good conservation condition. After a preliminary dry removal of the loose deposits by means of vulcanized latex sponges the cleaning was conducted with saturated ammonium carbonate solution applied by brush on pure cellulose sheets. Extensive washable tempera repainting, applied in recent restorations, was removed by swabbing with organic solvents. The consolidations were done with PLM AL injection mortar and the fillings with lime and sand-based mortar. Pictorial retouching was conducted with watercolors.

The

The The restorations: the faux marbles

The restorations: the faux marbles The restorations: the faux marbles (

The restorations: the faux marbles ( The restorations: the faux marbles (

The restorations: the faux marbles ( The restorations: the faux

The restorations: the faux

The restorations: the glazed terracotta crucifix

The glazed terracotta Crucifix, attributed to the Buglioni workshop, is dated around 1515. The work has probably undergone various shifts over the years, and it is not excluded that it was part of a more complete altarpiece, typical of the depictions of the della Robbia and Buglioni workshops themselves. The work, in fact, is mounted on a double wooden cross: the first smaller and older, the other more recent, probably made precisely to fit in the apsidal area behind the central throne. The Crucifix has an unusual molding, as the molding, from a side view, shows itself with meager thickness, while the head is made in high relief. Only the head is shown to be well hollowed out from the inside, while the entire rest of the figure has few hints of hollowing. The modeling consists of four portions: the legs, the part that includes the torso and the head, and the two arms. The composition is made to be self-supporting: each piece fits together with the adjacent one, supporting each other.

The work had a high layer of atmospheric deposit, as well as old, now altered pictorial additions present, particularly on the loincloth and arms. The left hand was totally detached and supported only by a few nails.

The current conservation intervention involved the removal of the Crucifix from the wooden supports. After that, a surface cleaning was performed, which included the removal or reduction to the level of the original surface of the old altered interventions. The detached hand was cleaned in fracture and glued in the correct position. Textural and pictorial additions of the gaps were made. Finally, the work was remounted on the two wooden crosses.

The

The The restorations: the glazed

The restorations: the glazed

The restorations: the bust of St. Miniato

The polymaterial bust from around 1420, made of wood, stucco and papier-mâché and depicting St. Miniato, the Armenian soldier who arrived in Florence where he was beheaded during the persecutions of Emperor Decius, becoming the city’s first martyr, is a sculpture known to art literature whose extraordinary beauty has suggested it as the author of the most representative Tuscan sculpture of the 15th century: Carlo Del Bravo referred it to Antonio Federighi; Martini attributed it to Nanni di Bartolo and Luciano Bellosi to Donatello because of its profound affinity with works of the second decade of the 15th century. The work is carved from a block of wood hollowed out on the inside; papier-mâché was used to make some parts of the interior of the drapery. The mantle is covered with a coarse weave cloth and ammannita to receive plaster preparation, bole and leaf gilding. In the wrists, the decoration has silver bulining and leafing.

During the preliminary stage of restoration, the work was subjected to diagnostic investigations by CT, RX, UV and IR followed by color and gilding investigations to understand the artistic technique and state of preservation. It was determined that the work was in a poor state of preservation. The polychromy of the fleshwork was obscured by repainting spread over time for devotional reasons: the face had been heavily ’refreshed’. Extensive lifting of the gilding was present in the robe and hair. The conspicuous punched texture on the edge of the robe, the tassels, the clasp clasping the tunic, and the crown were looking blurred and repainted.

In agreement with the Works Management, the work was disinfected with Permethrin, although the attack of woodworms was not active, as a future prevention. In some wooden parts where fragility was present, particularly in the neck, consolidation with Balsite resin was performed. Subsequently, stopping of the pictorial film was carried out with glue of organic origin and Japanese paper.

In order to characterize the pictorial surfaces to be treated, stratigraphic sampling and assays were carried out, which in the carnate identified three layers of pink color applied over as many plaster preparations. In the parts made shiny by the gilding (hair, mantle and robe) two applications of gold leaf with bolus preparation are noted. On the edges of the robe are traces of silver leaf. In the gilded crown are inserted gems made of pastille and glass paste. In the carnate, through gradual cleaning aimed at restoring the older pictorial layering composed of white lead and cinnabar, Solvent Gels with acetone and benzyl alcohol was applied then finished with several scalpel passes; in the gilding consisting of gold leaf gilding on red bolus preparation, a neutral fat emulsion was used repeated several times due to the presence of paints and mash applied over time.

This phase was followed by plaster and glue filling of the gaps present on the polychromy and the filling of the woodworm holes in the wood parts. The pictorial integration of the gaps present on the polychromy of the fleshtone was done by color selection with varnish colors; the gaps in gold were restored with bole and shell gold followed by a final Matt varnish protection in the gold and fleshtone.

The restoration recovered the expressive values of the bust conceived as a statue in the round. Also of extraordinary quality is the back carved and shaped with great skill in the articulation of the mantle resolved with folds of surprising beauty. The diaphanous polychromy of the light pink complexion of the young saint with a contemplative gaze with a crown on his head embellished with gems that sinks into the plastic mass of golden hair, like the jagged robe where the hands stand out in a refined pose, restores, to this painted sculpture, a luminous beauty almost as if it were an object of sacred jewelry.

The

The The restorations: the bust of

The restorations: the bust of The restorations:

The restorations:

The statements

“Just as the awe generated by the contemplation of the beauty of the Byzantine mosaic and the other precious marble apparatuses that anticipate here on earth something of the splendor of the Heavenly Jerusalem is ineffable,” says the Abbot of San Miniato al Monte, Father Bernardo Gianni, “so it is really just as difficult for us to find adequate syllables to express the joy, gratitude and admiration of the entire monastic community of San Miniato al Monte in the face of the competition of love, competence, dedication and, above all, selfless generosity that have made possible the enterprise now being carried out, under the scrupulous and participating gaze of the Florentine Superintendence and in particular of Dr. Maria Maugeri, by workers who with sleepless passion have restored this fundamental chapter of the art and architecture of Tuscany to its source of clarity. I wish to thank in a very special way and with everlasting and prayerful memory the extraordinary and constant commitment of the Friends of Florence to the preservation of the millenary heritage of San Miniato al Monte and, with a very special intensity, the truly exceptional commitment of the Simon family that gives to Florence and to the whole world so much rediscovered wonder.”

“San Miniato has always been in the heart of Friends of Florence: the support for the restoration of the Tempietto and the Chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal is only a few years old,” stresses Friends of Florence PresidentSimonetta Brandolini d’Adda, “these new interventions allow us to appreciate and experience in depth the beauty that the Abbey gives to those who enter it to pray, to know, to admire. The restorations make it possible to return to the community around the world, a heritage of inestimable value made up of details that finally become visible again and enrich a narrative that can be told for years to come. I would like to thank on behalf of our foundation Dr. Maria Maugeri a functionary of the ABAP Superintendency of Florence who directed the work, Abbot Father Bernardo Gianni and the Community of the monks of San Miniato al Monte for welcoming the restoration work, and the entire team of restorers who intervened on the works ensuring that all of us and future generations of people will be able to enjoy these masterpieces. And finally, a special thank you goes to our board member Stacy Simon who chose to support the restoration in memory of her husband Bruce: it is through her gift that we were able to carry out the entire restoration project.”

“A meticulous and thorough intervention that required great commitment and passion: being able to admire in all its beauty these restored parts of the Abbey is a true gift to the city and this is the extraordinary result of a great team effort,” stresses Deputy Mayor and Councillor for Culture Alessia Bettini. “We can only say thank you to Friends of Florence, which has always supported Florence’s artistic and monumental heritage. An example of generosity, active citizenship, love for Florence and for art and culture.”

“The restoration allows us to appreciate much more and better the entire presbyterial area, the sacred spice of prayer reserved for celebrations and monks, elevated from the hall and very rich in distinguished works,” says Superintendent Antonella Ranaladi. “The transepts, the pulpit, the Crucifix, the Bust of San Miniato, the frescoes and the splendid mosaics were restored and studied by excellent specialists. In the mosaic, one has recognized the original parts where the face of Christ, dating from around 1270, stands out precisely, from the later remakes and restorations including the extensive nineteenth-century ones. Moreover, one can appreciate the variety of materials, the manner of execution of artists and workers. These are works that were choral and become choral again in the completed restoration, thanks to the contribution of excellent specialists and the attention and generosity of Friends of Florence, which confirms here in San Miniato its love for Florence. Thank you.”

|

| Florence, restorations at San Miniato al Monte end after one year |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.