Did Andy Warhol infringe copyright? The U.S. Supreme Court will make a ruling

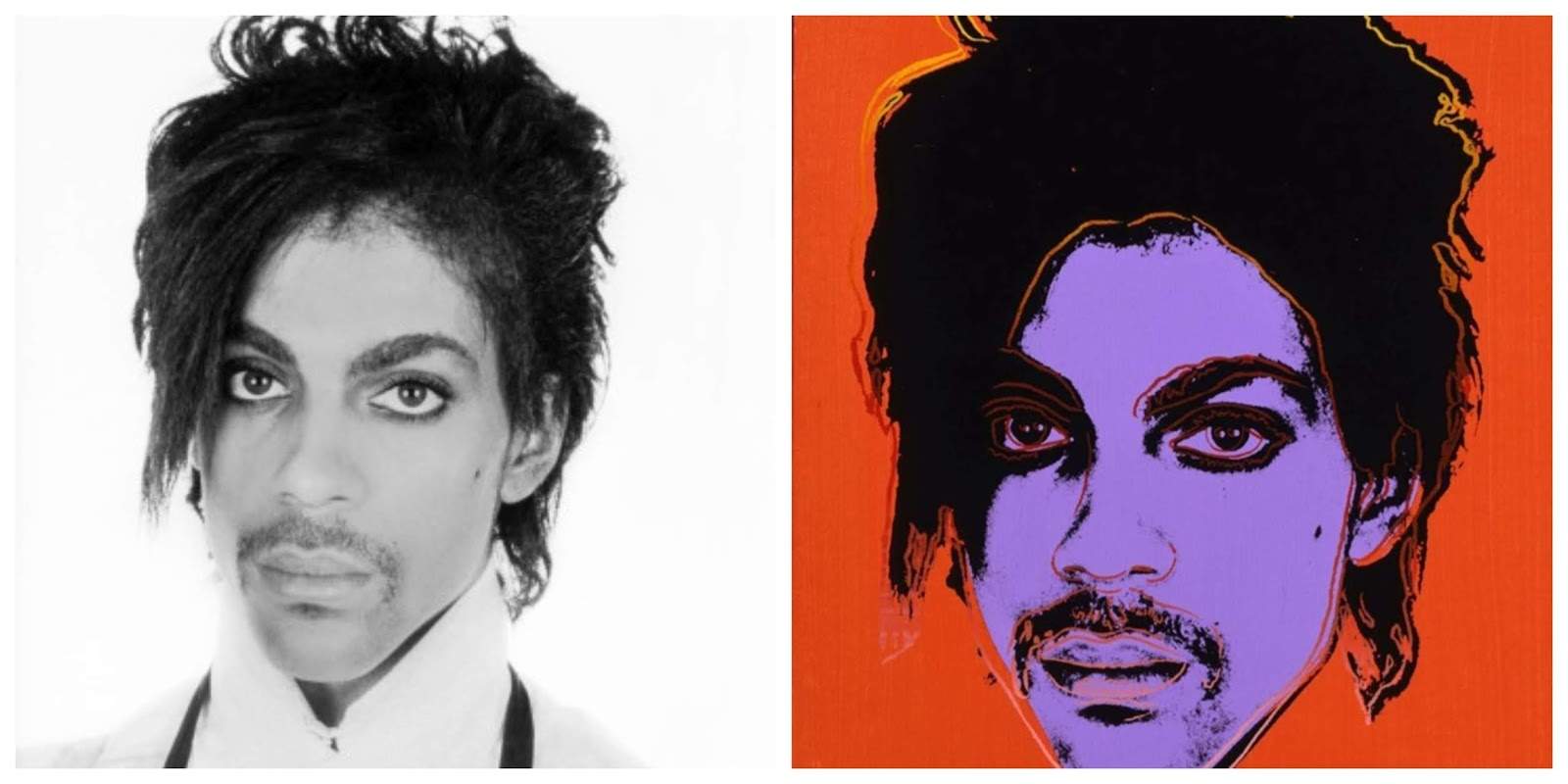

The U.S. Supreme Court, the highest federal court, assimilated to our Supreme Court, will rule on a case concerning the great Andy Warhol (Pittsburgh, 1928 - New York, 1987): in particular, the court will have to decide whether the father of Pop Art, with one of his works of art, was guilty of the crime of copyright infringement. At issue in this case are some images depicting singer Prince, based on a photograph taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith, one of the best-known music photographers in the United States. Goldsmith allegedly licensed the use of her photograph, reconstructs the New York Times, to Vanity Fair magazine for an article published in 1984, and Warhol allegedly used the same image, modifying it, to derive his work: specifically, the artist cropped and colored it to create fifteen images of Prince.

The dispute between Lynn Goldsmith and the Warhol Foundation started in 2016, when Vanity Fair published a special issue on Prince and the photographer learned of the existence of Andy Warhol’s portraits. It all revolves around the typically U.S.-based concept of fair use: in the United States, it is indeed allowed to freely use copyrighted works in certain cases, for example, the expression of the right to criticism or information, for educational or research purposes, as well as in the case when an author makes a “transformative” use of the protected work, that is, when he or she uses it to express something different and new than the original. In previous levels of adjudication, the Manhattan District Court judge had agreed with the Warhol Foundation, stating that the artist, with his work based on Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph, had in fact transformed Prince into an icon. Moreover, the ruling reads, “each work in the Prince series is immediately recognizable as a Warhol rather than a photograph of Prince, in the same way that Warhol’s famous depictions of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as Warhol and not as realistic photographs of those people.”

However, the ruling was overturned on appeal, with Judge Gerard Lynch ruling that the district judge should not have “assumed the role of an art critic and sought to ascertain the intent or meaning of the works in question. This is true both because judges are usually ill-suited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.” The judge’s task, according to the appellate ruling, is, if anything, to assess whether the later work is a derivative work and whether it retains the essential elements of the source material. And according to Lynch, Warhol’s work would preserve “the essential elements of Goldsmith’s photograph without significantly adding to or altering them.” In short, a completely different judgment than in the first instance.

The line that the Warhol Foundation’s lawyers also take is based on the fact that by transforming Lynn Goldsmith’s works, Andy Warhol also wanted to provide his own vision on issues such as celebrity and consumerism. Lynn Goldsmith’s attorneys, however, take a different view, stating that Warhol’s works “shared the same purpose as Goldsmith’s copyrighted photography and retained essential artistic elements of Goldsmith’s photography.” This is no small matter: the Supreme Court’s ruling could in fact rewrite the way artists cite or transform previously made works. Just think of all of Pop Art, postmodernism, or artists like Jeff Koons who have made appropriation a distinctive stylistic feature.

Pictured is Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph and portrait of Andy Warhol.

|

| Did Andy Warhol infringe copyright? The U.S. Supreme Court will make a ruling |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.