Zuchtriegel surprisingly reopens debate on Pompeii's eruption! August or October?

In a post on his socials on August 24, Pompeii Archaeological Park director Gabriel Zuchtriegel recalled theeruption of Vesuvius on August 24, 79 A .D .“On August 24, 79 A.D., the eruption of Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum,” Zuchtriegel recalled. "So wrote Pliny the Younger (the ancient manuscript tradition has only this date; all other dates attributed to Pliny are modern conjecture, as recently shown by P. Foss, Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius). Pliny wrote 17 years after the eruption; more than a century later, Cassius Dione will say it was phthinóporon (F. Montanari, Dizionario greco-italiano: propr. ’consumption of summer,’ hence ’autumn’). Some archaeologists have questioned the August 24 date, believing an autumn date more likely."

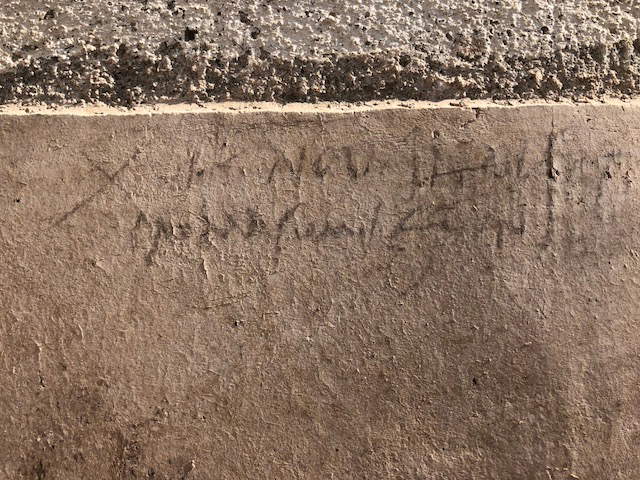

“Pliny therefore would have made a mistake-which is certainly possible, but so far diriment evidence is lacking. The search goes on, that’s part of its charm!” the park director concludes. The technical and seemingly innocuous post was actually undoubtedly weighed by Gabriel Zuchtriegel, because it has and will have paramount importance in the public (not scientific, but public) debate about the date of the eruption that destroyed Pompeii. And in fact it has created some consternation among some of the followers: over the past six years the hypothesis of the fall date of Pompeii’s eruption, and in particular the shift to October 24, has become de facto the institutional one. It happened, readers will recall, especially after October 16, 2018, when Pompeii Park, then headed by Massimo Osanna, announced that it had identified an inscription that “changes the history of the eruption,” dating it, it was claimed, certainly to October. It was a charcoal inscription found in a house in regio V that mentions “October 17,” without specifying the year. This then led to a massive media campaign, with the enthusiastic endorsement of then Cultural Heritage Minister Alberto Bonisoli (“today, with humility, we are rewriting history,” he told reporters that day ). Complicated by a series of past prime-time productions (the great popularizer Alberto Angela has long been persuaded of the late October date) that took the new October 24 dating for certain, for six years this created an environment in which doubts about the october date seemed to have no more citizenship.

Therefore, the Pompeii director’s “choice of field” will certainly help reopen a debate in which diriment elements were still missing. Zuchtriegel then responded to those who raised doubts about the soundness of his reasoning, dismantling in extreme synthesis the October 24 date: “On the date of October 24,” he wrote again on Instagram, "Pliny wrote the dates in the Roman way, that is, counting from the first day (the ’calends’) of the following month. So: August 24 = ante diem nonum kalendas Septembres, likely abbreviated a.d. viiii k Sept (cf. examples from Pompeian graffiti). Now, one of the manuscripts has ’non’ for ’nonum’ and then a gap. One editor reads ’nov(embre),’ which is why the November 1 date is also circulating. But it doesn’t end there: others decide both to accept nov(embre) and to keep nonum ... this is how the date of October 24 is born. The same word thus takes on two different meanings - ’ante diem non(um) k nov(embres)’ - which among other things are mutually exclusive. It is as if seeing a footprint of an animal and not being able to decide whether it was a dog’s or a wolf’s, one decides that both a dog and a wolf passed by. This does not mean that it was necessarily August 24. [...] The important thing is to look carefully at the sources and materials and to continue the scientific debate calmly and without bias." But what has happened then over the years?

What gives rise to the autumn hypothesis

In short, doubts about whether the date of the eruption dates to August 24 have existed for hundreds of years, both because some codices bear different dates and because the archaeological record has seemed over the years to several scholars to be ill-suited to an August landscape. Autumn fruits such as dried figs, walnuts, chestnuts and pomegranates, some wine containers already sealed, and braziers already in use in homes, as well as victims dressed in woollen garments, have been identified under the ashes.

In the latter part of the twentieth century it was particularly Umberto Pappalardo and Grete Stefani who strongly supported the idea of an error in the sources and proposed an eruption at late autumn or more precisely (this was their hypothesis) on October 24. Against this backdrop, in 2006 Stefani published a coin that-much more than the 2018 charcoal inscription-could be conclusive proof of the impossibility of a date of August 24, and so it was presented: a silver denarius of Titus that, the scholar explained, bore his fifteenth acclamation, which certainly took place after September 8, AD 79. The item was enthusiastically received by scholars and seemed to have cleared up doubts. But that was not the case: an autopsy look at the coin-whose designs alone had been published-exhibited in 2013 in London led some British numismatists to reevaluate it, noting that there were no discernible elements leading back to the fifteenth acclamation. It was not the “smoking gun,” as it was a coin datable generically in the summer-autumn of AD 79.

In this context, the charcoal inscription-which could also have been written in the years before the eruption-was one more element in favor of a possible autumn date (not October 24, any date after the 17th), but it could not be conclusive evidence, as it was presented and recounted instead.

The new post-2018 elements

Although Zuchtriegel does not explicitly say so in his post, new elements have emerged since 2018 that speak against a late October date. The first, and most important, is Pedar Foss’s study, Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius, cited in the post, which was published in 2022: the scholar, with a massive reanalysis of the sources, notes that in all of Pliny the Younger’s earliest codices (9th century CE) the date August 24 always appears, while all others are the result of additions by amanuenses in later centuries. In the absence of the “proof of the coin,” enough is enough to return to the view that an error in Pliny’s transcription is unlikely.

The second is a “discovery” from the period when Zuchtriegel was already director (June 2022), less scenic than others but rather interesting for possible dating implications: a tortoise found still with its egg about to lay, still with its soft parts. Since it is highly probable that it died in the days of the eruption (tortoises are normally found without the soft parts), it helps make an October event unlikely, since tortoises do not lay eggs at that time.

The debate, let’s be clear, is still far from over. The “autumnal” landscape, with pomegranates and figs, can and should leave open doubts. The grape harvest, however, as far as we now know, had not yet begun, except in a few cases, as archaeobotanists (particularly Antonia Ciarallo) have made clear.

“For the Romans August was autumn, we know this from a good part of the ancient authors for this reason some fruits that may sound strange to us today, it is absolutely normal that they were ripe already in August,” explains Helga Di Giuseppe, a researcher who has been working on Pompeii for decades and who is strong proponent of August dating, so much so that she even dedicated a book(Pompeii, the Catastrophe, Science and Letters, 2022, written with Marco Di Branco) precisely to the alleged academic-scientific damage to the media narrative of Pompeii between 2014 and 2020. Di Giuseppe understandably welcomed the “reopening” of the Park’s management to August dating: “By now it will not be easy, in these years they have changed even the textbooks, October dating has become the official one everywhere.” But having a director of Pompeii who reopens to scientific debate will surely make it easier to start again with firm data.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.