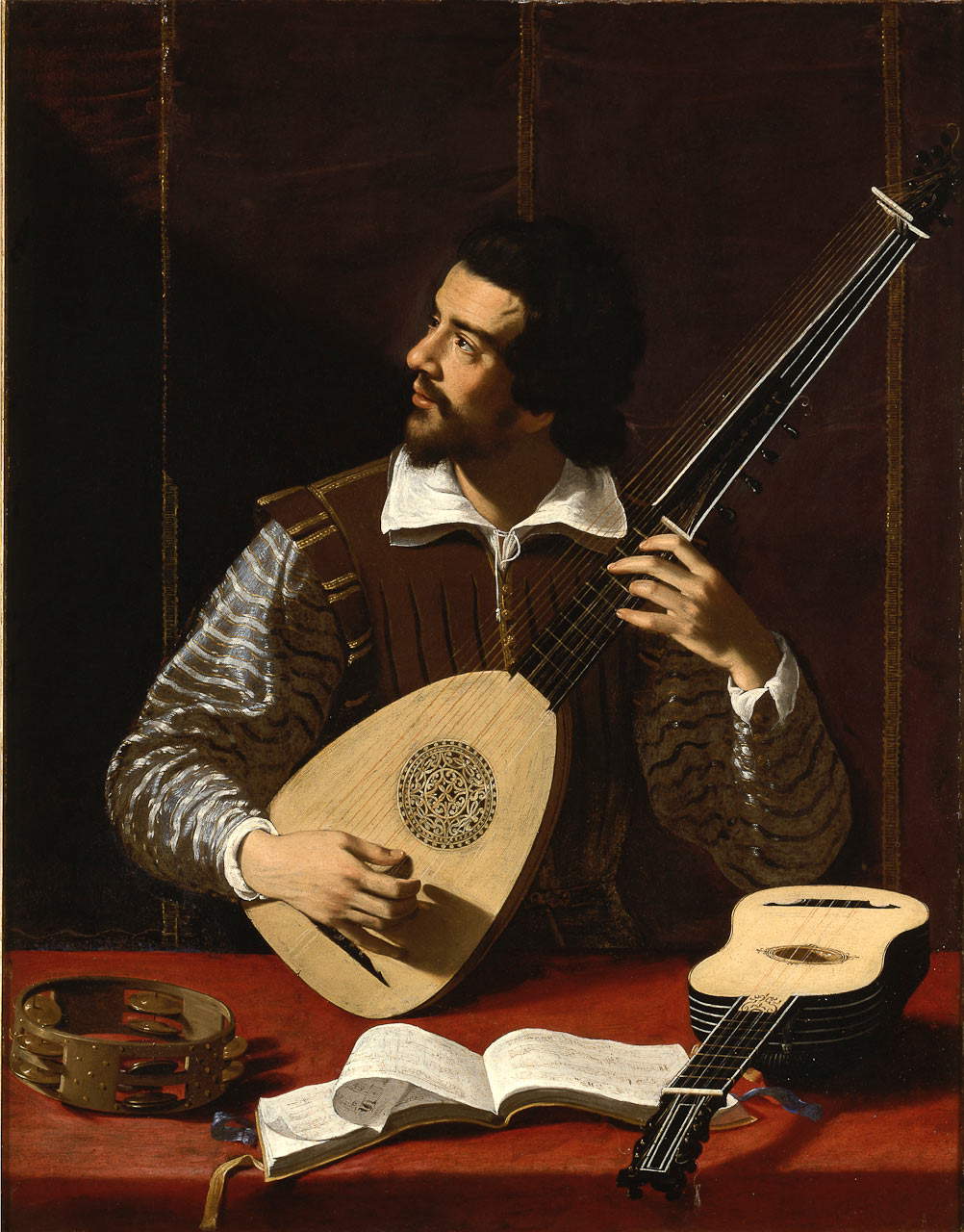

It is indeed an exceptional discovery that has been announced by the Caretto & Occhinegro Gallery in Turin: the antiquarians Massimiliano Caretto and Francesco Occhinegro have in fact made public the discovery of the Concerto by Antiveduto Gramatica (Rome or Siena, 1571 - Rome, 1626), the missing part of the very famous Suonatore di tiorba, the symbolic work of the Galleria Sabauda in Turin, a piece of such high quality that it was once attributed to Caravaggio. The work’s original appearance, an Allegory of Music, was known only through copies and historical accounts: the missing part, with the clavier player and flute player, was thought to be lost. It was originally a three-figure scene of sought-after compositional harmony, cut down in the course of history probably (although this is only a hypothesis) to make two pieces and thus obtain a greater profit on the market.

The composition was known from an early copy first published in 1922: the “whole” painting developed horizontally and featured three characters: the flute player, the singer engaged in accompanying herself on the claviorgano, and the theorbo player. Until now we knew only the Theorbo Player preserved in the Sabauda Gallery. For studies on Gramatica, but more broadly for studies on the development of the Caravaggesque revolution, the find is of truly significant significance.

A Caravaggesque of the first hour, Gramatica, in 1591, when he was only 20 years old, had already set up his own workshop where, before 1593, a young Caravaggio, a contemporary of his Sienese-born colleague, would also work for some time. “Musical” subjects, such as players and concerts, are quite frequent in his production, deriving from his closeness to Caravaggio and his circle: however, Gramatica’s Caravaggism is diluted by a formal research that saw its presuppositions in the great painting of the sixteenth century (Raphael would remain an unavoidable model) and that would later bring the artist closer to a classicism close to that of the Bolognese, above all Guido Reni and Domenichino. At the time of the probable creation of theAllegory of Music, Gramatica nurtured interests that pointed in a specific direction: the artist found himself, wrote the art historian Gianni Papi, author of the first monograph on the painter and his greatest specialist, “at the center of a cultural (and also artistic power) circle that had to involve - to varying degrees and more or less temporally - artists of great weight, such as Borgianni, Vouet and Serodine, and others less gifted and more bent on the classicist phase of the master (to the point of blending in with it).” Inevitable, then, is Gramatica’s “adherence [...] to the Caravaggesque movement,” which is especially noticeable in the still life pieces, in the years just before 1610. The Concert figures among the typical products of this period of Gramatica’s activity, and the Theorbo Player, the right-hand side of the once whole painting, had risen almost to an icon of his production, and is probably his most famous work. And it was precisely Gianni Papi on the occasion of the discovery who draftedan accurate and specific study(Antiveduto Gramatica, a rediscovered Concert Scene) that accompanies the work. A work that, now, is revealed in all its exceptional quality. The two figures, the flute player and the singer, emerge from a somber background, described with delicate verisimilitude, on a par with their separate companion. Exceptional are the chiaroscuro pieces that give volume to the figures: admire, in particular, the player’s hands. Admirable is the way Gramatica describes the sumptuous fabrics and gems decorating the singer’s bodice. At last we can also return to appreciate the other half of Gramatica’s masterpiece.

We know the recent history of the Theorbo Player, which arrived at its present location with the Falletti di Barolo donation, which also included Gramatica’s other painting now in the Sabauda (the Saint Praxedes and Saint Pudenziana). The work, as recalled in the opening, has long been referred to Caravaggio (by scholars such as Jacob Burckhardt, Emil Jacobsen, Alessandro Baudi di Vesme, in the Turin museum catalogs of 1899 and 1909, then again by Wolfgang Kallab and Lionello Venturi, to arrive at the Florence exhibition of 1922 still assigned to Michelangelo Merisi), until Roberto Longhi ’s 1928 intervention, which confidently ascribed it to Antiveduto, recognizing in the Turin canvas a fragment of a three-figure musical composition, a copy of which had resurfaced in 1922 in the Michelsen sale at Bangel in Frankfurt (cat. No. 1030, April 2, 1922, lot 127, attributed to Simone Cantarini). The copy, whose current whereabouts remain unknown, was published in 1971 by Richard E. Spear, and it was on that occasion that Spear, at the suggestion of William Chandler Kirwin, is said to have established the connection between the composition of which the Suonatore was a fragment and a painting that belonged to Cardinal Del Monte, recorded in theinventory compiled after his death in February 1627. Indeed, theinventory lists “A Painting with a Music by the hand of theAntiveduto with a Negro Frame longo Palmi six high palmi five.” Spear pointed out the almost exact correspondence between the height of the Turin painting and that of the work mentioned in the Del Monte inventory, and between both the dimensions of the Bangel copy (measuring 120 x 141 centimeters) compared to those of the “Music” mentioned. The Roman palm measured about 23 centimeters, so the Del Monte canvas had dimensions around 115 x 138 centimeters, and the Sabauda canvas measures 119 centimeters in height and 85 in width, leading to the inference that the Bangel canvas has dimensions almost identical to the painting to which the Turin Suonatore belonged.

The minimal difference from the measurements of the Del Monte’s Musica dellInventario convinced Spear early on about the correspondence with the image handed down from the Michelsen copy, and thereafter no objection was ever raised. Not only do the measurements support the identification: although it may seem a little vague, the term Musica is used on other occasions in the Del Monte inventory, to connote scenes in which the protagonists play or sing. The same term, in the same inventory, is also used for the Musica di mano di Michelangelo da Caravaggio con cornice negra di palmi cinque in circa, that is, for Merisi’s Concerto (also known as I musici), now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Finally, the description of a painting by Antiveduto recorded in theInventario dei beni passati al vescovo Alessandro Del Monte (heir of Francesco Maria’s brother Uguccione), written on August 23, 1628, would seem to further confirm the correspondence with limmagine handed down from the Bangel copy and, today, from the two parts in the original (the instruments described are the same and the characters are three).

After that, the news comes to a halt. We know very little about what happened to Gramatica’s “Music” after 1627. The Concert found in Greece, as mentioned, was given up for lost, while the first news about the solo Theorbo Player dates back to the first half of the 19th century, when the painting belonged, along with Saint Praxedes and Saint Pudenziana, to the collection of Marquis Carlo Tancredi Falletti di Barolo. After the latter’s death in 1838, his widow bequeathed the two paintings to the Royal Picture Gallery of Turin (today’s Galleria Sabauda) in 1864, but the Suonatore must have already been on loan at the museum because Jacob Burckhardt described it in 1855. Scholars have not yet traced, even when the Concert was found, previous provenances of the canvas: therefore, there remains a period of silence around the work from 1627 to the beginning of the 19th century. It is also difficult to determine when the Music was cut and the two parts divided.

Recently, Del Monte’sAllegory of Music has been the focus of a 2015 study by Piera Tordella, who proposed to identify in the two protagonists of the scene, the theorbo player and the singer accompanying herself on the claviorgano, two famous personalities of the time: the composer and musician Cesare Marotta and his wife, the singer Ippolita Recupito, one of the most famous in Italy in those years. The same conclusions had already been reached in 1997 by musicologist John Walter Hill. If the identification with Ippolita Recupito can be corroborated by the resemblance to her portrait executed by Ottavio Leoni, the same cannot be said for her husband, so much so that there were those who, like Domenico Antonio D’Alessandro, proposed identifying him with the lutenist Vincenzo Pinti. Marotta and Recupito were in the employ of Alessandro Damasceni Peretti (Cardinal Montalto), at least since 1603, and regularly received a monthly salary of 25 scudi. Cardinal Del Monte’s documented friendship with Montalto and their

As for chronology, Papi, anchoring precisely on speculations about musical culture, proposes a date of 1608-1610, in close connection with the spread of monodic singing. Such an early dating reiterates the importance of the painting as a historical document, since it is a precious testimony to the diffusion and success of monodic singing in Rome, to the point that Cardinal Del Monte boldly declares (with respect to the previous musical tradition) that he was an immediate supporter of it, precisely by commissioning Antiveduto to paint this painting. With works such as these, Gramatica is part of that still small patrol of artists responsive to Caravaggio’s revolution, who repropose its themes and stylistic cipher: in particular, he can be compared to that group of artists, among whom are Giovanni Baglione, Orazio Gentileschi, and Paolo Guidotti (to limit ourselves to some of those who are certainly documented to us), who radically changed their ways, coming from an earlier and honorable career in the late Mannerist painting of the great pontifical sites of the late sixteenth century, and turned toward the innovations introduced by the Lombard, while each preserving his own personality.

The painting proposed by Caretto and Occhinegro was found in a Greek collection by London dealer Derek Johns, who subjected the canvas to a lengthy examination, at the end of which Gianni Papi drafted the above study, which explains in detail the genesis of the work, the attributive question and the technical condition. The work, in fact, beyond the exceptional and obvious level of quality, style and clear connection with other works by the Tuscan-Roman master, reveals some irrefutable technical and documentary evidence. In his study, Papi, who omits no aspect, traces and contextualizes the documentary, technical and historical evidence: among the most noteworthy elements are the inscription “Dadiva de Torlonia” on the back of the canvas, and the collector’s mark “T.94” (this is the attestation that in the past the work passed through the collections of the Torlonia family, who marked their pieces with similar initials, according also to what the scholar Rossella Vodret, heard from Caretto and Occhinegro, confirms), in addition to the measurements that correspond to those of the inventory, not to mention, of course, the difference in quality between the work and later copies.

According to Caretto and Occhinegro, the most sensational results, however, are those that emerge from the diagnostic examinations: the canvas, in fact, turns out to have been cut and modified to create an autonomous composition so as to hide the parts that directly link the work to the Suonatore di Tiorba di Torino. The X-rays have very clearly demonstrated the re-deployment of the original canvas in order to enlarge the composition on the side and obtain, thus, an autonomous painting. In all likelihood, the painting was resected already in ancient times, perhaps between the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. As anticipated, the work was perhaps cut for commercial reasons: the painting was in fact sold abroad, where it had been for centuries at the time of rediscovery. The recovery of the second part, which is in a sensational state of preservation, leaves out the possibility that the separation of the two parts was due to an accident to which the left section of the canvas had fallen victim. We do not know when the cut dates back: the hypothesis that suggests a very ancient operation is, however, supported by the fact that several seventeenth-century copies of the Suonatore di tiorba are known to correspond faithfully to the Turin Cardinal, evidence that the Del Monte composition was divided perhaps not long after the cardinal’s collection was dispersed.

To obtain the rectangular shape that the painting currently shows, the canvas was cut to a height of about twelve centimeters, tearing off a strip that included the lower part of the harpsichord and the acute angle of the table, down to the tambourine that instead remained in the Sabauda Gallery canvas. This strip was shaped and sewn along the cut edge of the singer (i.e., along the head and sleeve of her dress): its underside thus corresponds to the current right side of the canvas as we see it today. On that applied part a music booklet has been repainted on the lower right side, somewhat inspired by the one in front of the theorbo of the Sabauda’s Suonatore.

The painting was also analyzed by Anna Maria Bava, director of the collections of the Sabauda Gallery, who conducted some investigations on the painting kept in Turin, confirming what had already emerged from the canvas proposed by Caretto & Occhinegro: the extent of the cut, its typology and the results visible from the X-ray coincide “excitingly,” say the two antiquarians. This part of the work was also subjected to a stitching using a coeval canvas to fill the missing space: a coincidence at the level of an evidentiary accident that reconstructs without doubt the dynamics of the events. After cleaning and restoration (minimally invasive, considering the surprising state of preservation of the surface), the sumptuous chromaticism emerged, which is especially exalted in the singer’s precious dress, adorned with pearls and jewels. Also characteristic of Antiveduto Gramatica is his care in rendering women’s hairstyles, with abundant and soft hair, arranged in a very elaborate way, so much so that the historiographer Giulio Mancini could not help but notice how at times the painter emphasized this physical aspect far too much (“he exaggerates in doing the hair,” wrote Mancini in his Considerations on Painting of 1617, written therefore when Antiveduto was still alive). Also of particular note is the precise rendering of the instrument played by the singer, a claviorgano.

The Concerto now stands as a candidate to enter the collection of the Sabauda Gallery: the hope is that the state will be able to purchase the newly found work so that the two players of the Concerto can find their companion in the halls of the Turin museum. It would be one of the most important purchases in recent years. “It is clear that such a find has something sensational about it, and we do not think we are exaggerating in saying that, for the Sabauda Gallery, this is the discovery of the century,” say Massimiliano Caretto and Francesco Occhinegro.

“Even though we are specialists in Nordic schools, a painting like this, with such a fascinating history, did not leave us indifferent, and, as Torinese, we immediately mobilized to attract as much attention as possible from the city museum,” add the two young antiquarians from Turin. “We would like (as would everyone, we believe). that the work would become part of the Savoy collection, being able to showcase it next to the player. Of course, this is a very special situation, as the work has not been in Italy for centuries already, but this is one of those cases where a purchase by the state would be more than desirable. After all, we contacted the institutions already last year, although we know that the funds available are often very scarce. However, we want to raise public awareness of the matter, perhaps hoping for the intervention of one or more institutions to help the museum: it would be an uplifting conclusion to the affair for everyone.”

The work will be exhibited for the first time to the public during the TEFAF fair in Maastricht, which will be held from June 24 to 30 in the Dutch city: in Caretto & Occhinegro’s booth it will be possible to observe the precious find up close and live.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.