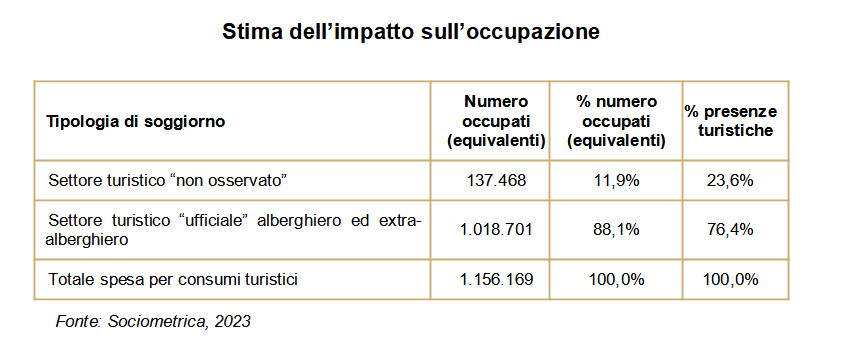

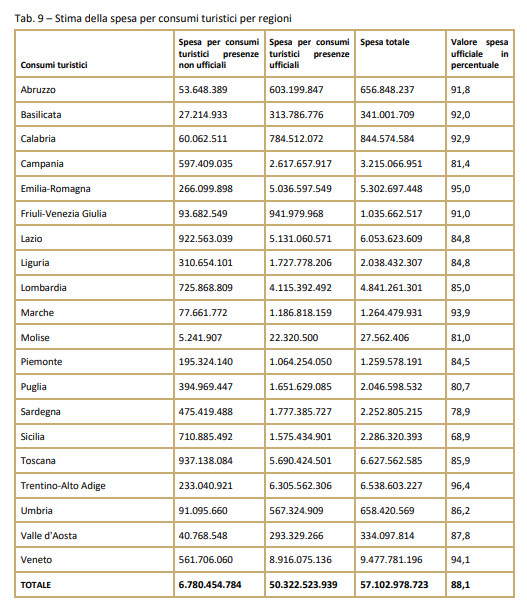

Making a careful analysis on the different scenario that tourists who choose to stay on vacation in a hotel compared to those who choose to rent an apartment for short periods (under a week) have taken care of it, Federalberghi, commissioning a study on the subject from Sociometrica directed by Antonio Preiti, a tourism expert with whom Finestre Sull’Arte had already had the opportunity to speak on the subject. The study was presented during the hoteliers’ association’s 73rd national assembly. The study that Sociometrica conducted on the top 500 Italian municipalities with a tourist vocation shows that there are more than 57 billion euros in tourism consumption realized in 2022, of which 88 percent (50.3 billion) are related to official presences and 12 percent (6.8 billion) are related to “unobserved” presences. Unobserved overnight stays, which account for 23.6 percent of tourism flows, generate only 11.9 percent of consumption and, consequently, a similar percentage in wealth creation and employment.

The study compares two models: the first is based onhotel hospitality, the second on the marketing of short-rental houses, which we have already discussed on these pages. Both models aim to provide hospitality to overnight guests in a tourist destination, but the economic consequences are very different, and, as we had pointed out, they also bring about social, urban planning and commercial changes in the historic centers of our cities. Introducing it, Federalberghi president Bernabò Bocca wanted to emphasize how the hotel is “the fulcrum on which the whole great hospitality machine plays. Its value lies not simply in its turnovers, in its economy in the strict sense, but in the expansive effects it is able to spread to other sectors.”

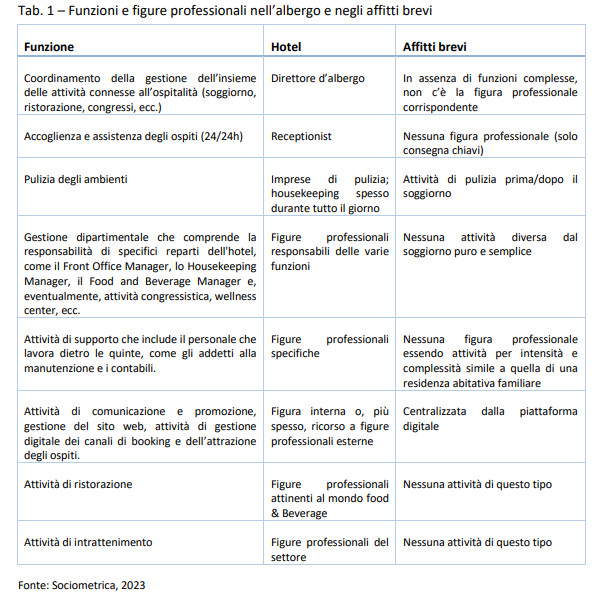

According to Sociometrica’s study, “the economy generated by official presences covers a total value that manages to finance more than one million jobs, while the economy based on unregistered presences generates just 137 thousand jobs. The major contribution that hotels make to employment growth is also determined by the presence of a complex business organization, with professional figures of various specializations and the ability to create and spread a multiplicity of economic interdependencies that produce employment and income. This multiplicative capacity is quite meager in the case of short rentals, whose operations, almost always, are limited to the delivery of keys, final cleaning of rooms and routine maintenance.”

So in both cases we have tourist presence but the scenarios are very different and, we would add, in short term rentals we are even moving toward eliminating even the step of handing over the keys. Very often, in fact, the tourist finds on the front door a keypad on which to type a code to enter the building (sent to him via text message at the time of online payment) and at the front door a box attached to the handle where to enter a combination and when it opens you find the key to open the door. What started out as a chance to experience a vacation immersed in and in contact with local people (in spite of hotels considered devoid of local feeling and characteristics) becomes a journey into utter anonymity. Not even a greeting with the host. And to think that slogans and TV commercials of online platforms sponsoring the use of homes instead of hotels pointed precisely to the possibility of living the vacation as an immersive experience already from the accommodation used by the inhabitants of the place chosen to visit.

The study recalls how “the universally adopted indicator for evaluating the performance of the hospitality economy is given by tourist presences, that is, the number of nights spent by guests in hotel, non-hotel or other more informal arrangements. However, as can be easily guessed, this indicator is not economic in nature; it merely reports the phenomenon in a general way. To show how wrong, or at least insufficient, this approach is, a few analogies suffice: the textile industry is not judged by the sheer number of garments sold; nor is the automobile industry evaluated solely on the basis of the number of vehicles purchased (in that case, some countries in the Soviet area would have been at the top of the world rankings of automobile manufacturers), but it is evaluated on the basis of the number of goods sold multiplied by their economic value.” We therefore have the need, in order to have an exact tally of the economic weight of tourism, to estimate these presences and define their economic value. Tourism then, we understand, is a vast and cross-cutting dimension in our society that determines various options of scenarios whose indicators must be carefully chosen and evaluated.

Tab.

Tab.

“Rarely,” he continues, “is it thought that even in tourism there is a need for choice, because when things are configured by themselves, haphazardly, piece by piece, without a design, a destination risks being the object and not the subject of development. Where design is not the old, inadequate and outdated, programming, but the guiding ideas that each destination, in a shared way, decides to follow in order to get the maximum benefit from tourism.”

There are many ways in which a tourist destination develops: and while it is always true that the raison d’être of the phenomenon is the attraction of places, it is also true that that destination can develop in various ways and with different results in terms of economic impact and the urban identity of historic centers, but the bottom line is that the sum of the houses does not lead to complexity. For example, if we compare a set of 100 dwellings with a hotel of 100 rooms, the sum of the dwellings does not create new professional figures, it simply adds up the elementary functions of which the single offering is composed.

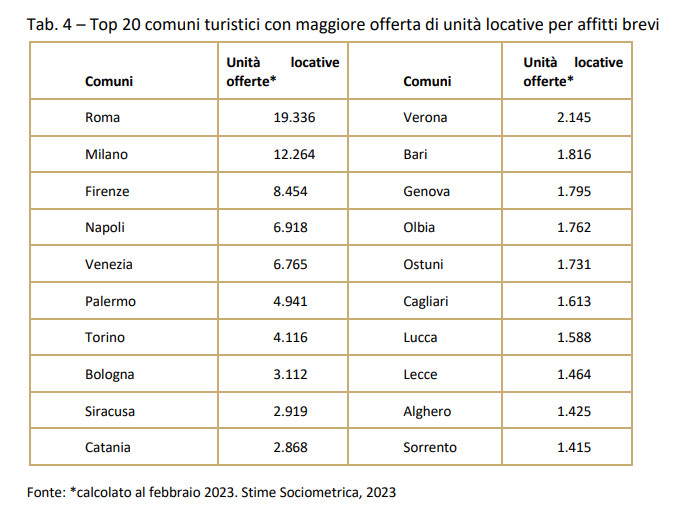

The top 500 Italian tourist municipalities (3,390 out of about 8,000), which account for as much as 83 percent of the added value of Italian tourism, were considered for the research. It is interesting to see the ranking of the top cities with supply of short rental units on the major online platforms (Tab. 4). As can be seen among the top 20 destinations, 16 are cities, while the remaining 4 are beach destinations, which naturally grow as availability in the summer period. For example, Olbia comes in at 3,048, placing ninth in the ranking and Alghero with 2,425 in eleventh. We will see later how especially in the south the weight of the supply of short rentals is very substantial. For the time being, the conclusion is that the phenomenon has developed mainly in large cities of art and then in medium-sized cities of art and finally in southern seaside destinations.

We can therefore say from Preiti’s analysis emerges how while for the small country or seaside town the presence on the platforms turns out to be an unparalleled advertising showcase at zero expense to make oneself known (and as the study confirms in our consideration, renting a house is often the only opportunity in the vast majority of small localities that lack hotel facilities. In short, renting a house online is the only way to bring tourism to inland areas or areas that are off the beaten track. And bring wealth therefore to these small towns) for the cities of art the phenomenon has become of such a magnitude that it has developed what are risks of unforeseen negative effect. “Short rentals” are a “problem” only for art cities and “today that level is not dissimilar even in medium-sized cities with high artistic value, which we can define as ’second best.’ In southern seaside destinations, the phenomenon generally does not develop, except in part, in historic centers, but maximally involves second homes for vacation use.”

Preiti shows us how the jagged presence of hotel principals leads us to have two models of tourism growth based on the different type of accommodation: “the first model has the driver in the greater hotel presence and the second is driven, on the contrary, by the supply of second homes” that are decisive for the development of locations where the hotel structure has never arrived or has closed over the last two decades.

Tables prepared by Sociometrica make the situation clear at a glance Considering, as always, the top 500 Italian tourist municipalities we see that as of February 2023 205,546 housing units are available on online platforms. If, however, we consider the summer period, then the supply grows to 267,076, which is 61,530 more. It is interesting to see the ranking of the top cities with supply of housing units for short rentals on the major online platforms (Tab. 4). As can be seen among the top 20 destinations, 16 are cities, while the remaining 4 are beach destinations, which naturally grow as availability in the summer period. For example, Olbia comes in at 3,048, placing ninth in the ranking and Alghero with 2,425 in eleventh. We will see later how especially in the south the weight of the supply of short rentals is very substantial. For the time being, the conclusion is that the phenomenon has developed mainly in large cities of art and then in medium-sized cities of art and finally in southern seaside destinations.

We have so far analyzed the size of rental units, but in order to understand their actual economic weight, we must also consider their occupancy rate on an annual basis. The average occupancy rate calculated over the 500 municipalities is 55.1 percent, but there is a wide range of variation in the distribution, thus making it appropriate to highlight some specific situations of particular interest.

The tourist destination with the highest occupancy rate is Rome, which reaches 88 percent, followed by other medium and large cities, including Florence, Bergamo, Padua and Venice. Among the top ten tourist destinations, there is only one beach destination, Positano, which attracts customers even off-season due to its characteristics, and Bellagio, a lake destination with a high degree of attraction year-round (Tab. 5)

Cross-referencing the data, again done by Bank of Italy, between level of spending and type of stay allows us to distinguish between the consumption of one and the other type. Therefore, let us consider, as already described, (Tab. 3) the total per capita expenditure per day of a guest in a hotel worth 156.20 euros and the equivalent type of expenditure for those who are guests in a short rental of 68.20 euros. Using these parameters we will be able to calculate the total tourist consumption expenditure of both the share of the market that goes to hotels and the share that goes to short-rental house offers.

The author of this article: Andrea Laratta

Giornalista. Amante della politica (militante), si interessa dei fenomeni generati dal turismo, dell’arte e della poesia. “Tutta la vita è teatro”.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.