There is a new Melozzo da Forli. Extraordinary discovery in Perugia

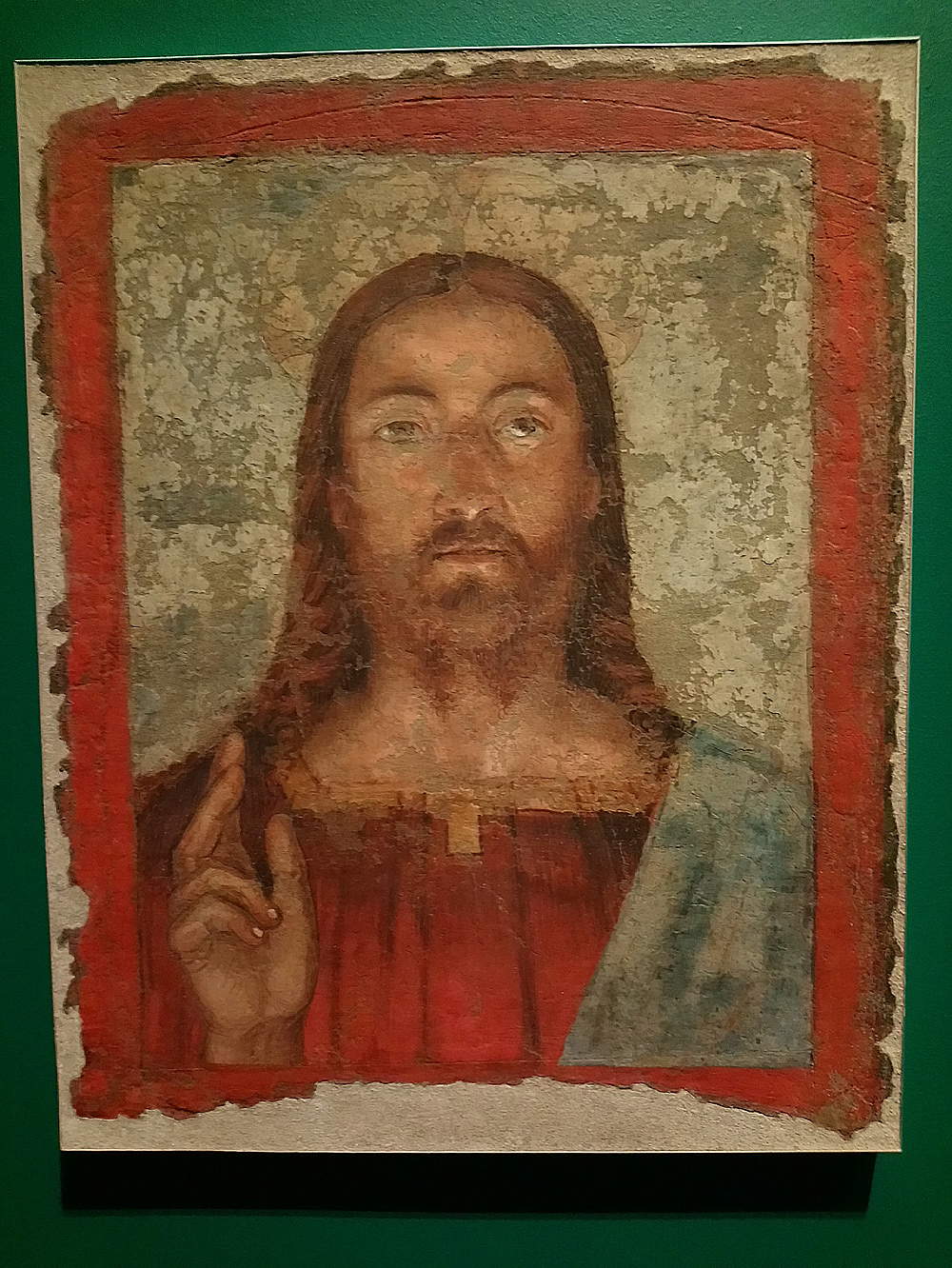

A new work by Melozzo da For lì (Melozzo degli Ambrosi, Forlì, 1438 - 1494) has been discovered: it is a Salvator Mundi “re-emerged” from the storerooms of the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia, on the occasion of the exhibition L’ altra galleria, which opened on September 22. This is an extraordinary discovery, certainly one of the most important in recent years, and even though it has not yet been published in scholarly circles (it will be shortly), several scholars who have had the opportunity to view the painting have spoken favorably about its attribution to the Forlì master. The discovery is all the more remarkable when one considers that Melozzo da Forlì is an extremely rare painter: a total of about twenty movable works that are referred to him (including detached frescoes and fragments of wall decorations), to which are added fresco cycles and a scant group of attributed works.

The first person to formulate Melozzo’s name for the painting, a fragment of a fresco reported on canvas, “rediscovered” in the deposits of the Umbrian museum, was the art historian Gabriele Fattorini, a specialist in the fifteenth century and a student of Luciano Bellosi, whom we reached to let him tell us the details of the amazing discovery and whom we thank for his availability: specifically, this is a work covered by later repainting, and for that reason it was thought to have been executed in the fourth decade of the 16th century by an anonymous Raphaelesque painter. “When I saw this painting in its grid, in the storerooms of the National Gallery of Umbria,” Gabriele Fattorini told us, “I asked to have it looked at, and it seemed to me to be a painting of great quality, although very, very ruined. So I asked for an opinion from the director, Marco Pierini, telling him that in my opinion it was worth restoring it, so that I could see what came out of it, because to me it looked like it could be a work referable to an important hand of the second 15th century.”

|

| A room in the exhibition The Other Gallery at the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Melozzo da Forlì, Salvator Mundi (1475-1485; detached fresco reported on canvas; Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

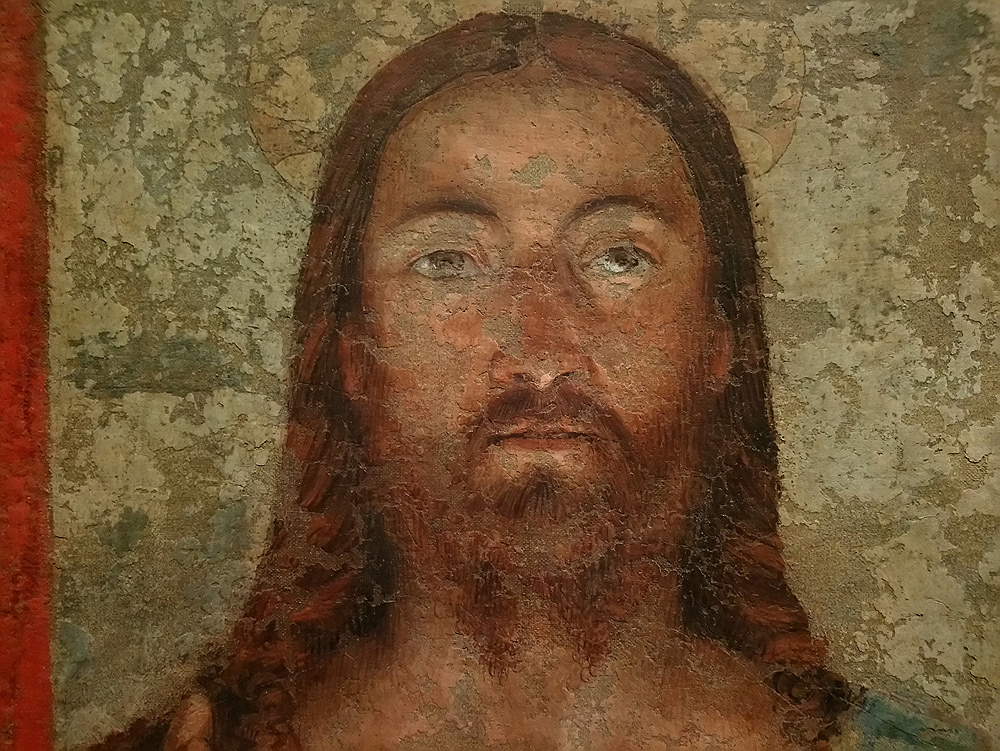

| Melozzo da Forlì, Salvator Mundi, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

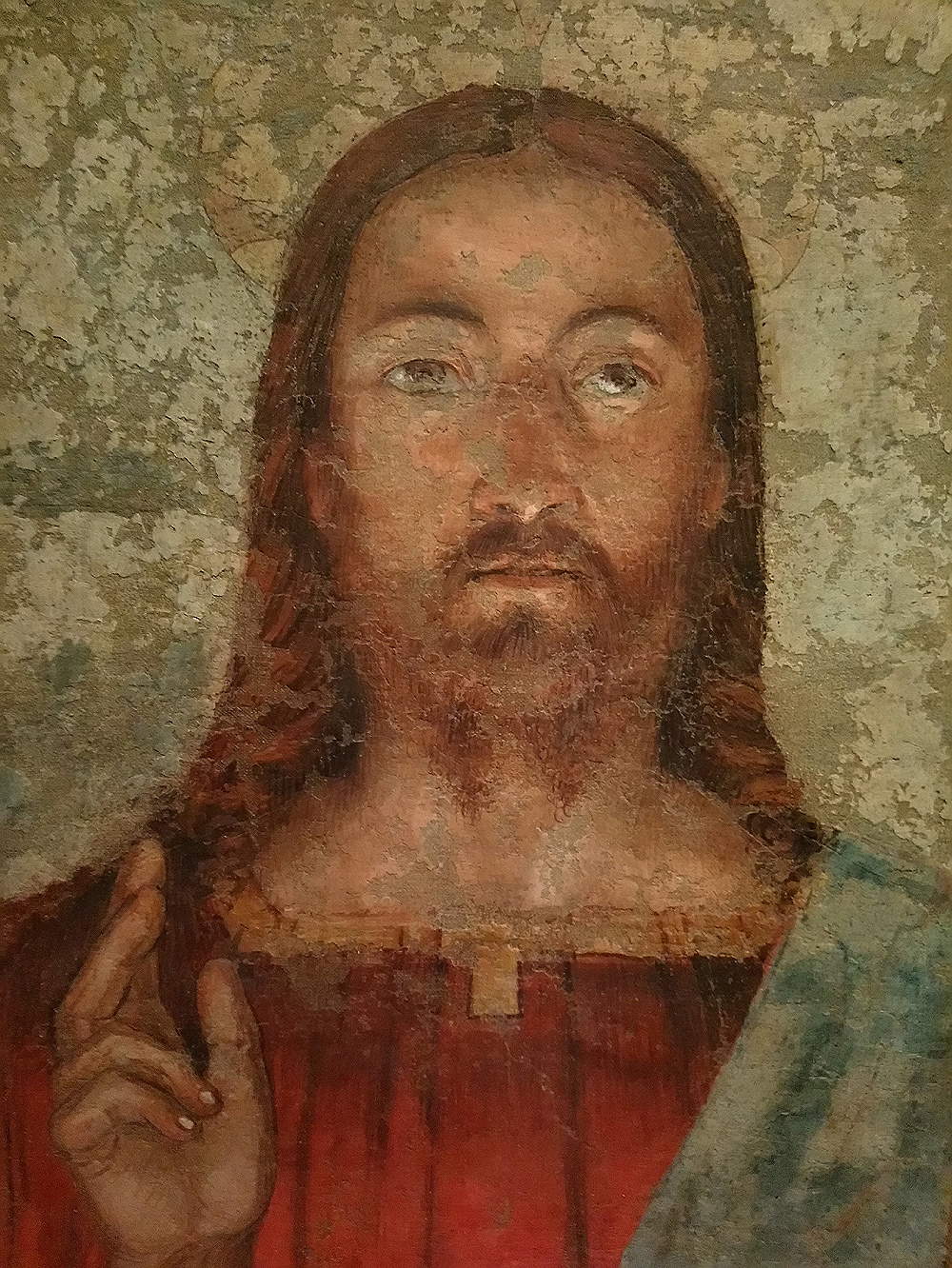

| Melozzo da Forli, Salvator Mundi, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre sull’Arte |

The restoration was then conducted on time, by restorer Francesca Canella. It was an underestimated work, the scholar explained. “It is in fact from Palazzo Pontani,” an ancient 15th-century building in the historic center of Perugia. “The problem is that the paintings from Palazzo Pontani were detached during the nineteenth century (also with detachments of unexceptional quality), ended up in the Gallery, and were all referred, by virtue of the age of the main cycle in one room, to the 1630s, and were labeled as the work of a Raphaelesque painter of the 1630s. It has to be said that the main cycle in Palazzo Pontani is not something extraordinary, but this work has nothing to do with that cycle, it’s obvious, because if you look at it you understand that it is just completely different.” Over the centuries, the painting that is now attributed to Melozzo underwent rehashes that heavily altered it. “But once it was restored, on the occasion of the exhibition,” Fattorini continues, “the repaintings of the old 19th-century or even later restorations, which tended to make it look like a 16th-century, Raphaelesque work, were removed, and therefore a much much much brighter painting emerged, a painting by a master who had seen Piero della Francesca, who had moved from Piero to then take his own personal path. So, granted that it probably really comes from there, from Palazzo Pontani (but for that we will have to do further research), there is the question of whether in any seventeenth-eighteenth-century source the painting is mentioned, perhaps not with the attribution to Melozzo. But I think that name can be aimed at, despite the work’s unexceptional state of preservation. I have also reasoned about it with Marco Pierini and other friends.”

Fattorini and director Pierini, in fact, are not the only scholars who have seen the painting, which from September 22 everyone can admire in the exhibition rooms at the National Gallery of Umbria. “I talked about it with Alessandro Angelini,” Fattorini says. “As said, as soon as I saw it in the grid I realized it was an important painting. Then I sent the picture to Alessandro, and he replied agreeing that we were dealing with a remarkable artist. Then he saw the painting again from life: the effect was not extraordinary because of the repainting, but after I sent him the photo of the work after restoration, he was impressed. Then I mentioned the discovery to Andrea De Marchi: we exchanged messages, and he too agreed that it could be the work of Melozzo.”

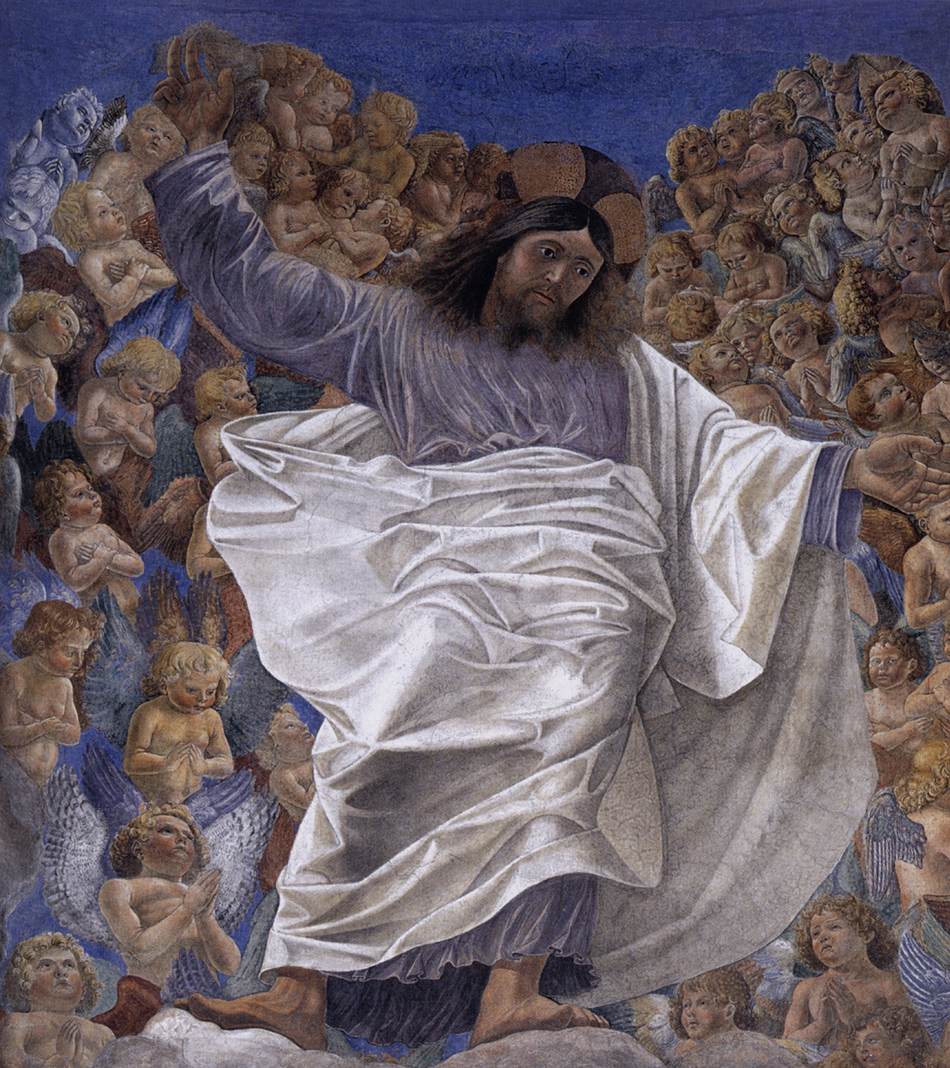

We also asked Gabriele Fattorini what were the decisive elements that could play in favor of Melozzo’s name. “The use of light, basically,” the art historian explained. Just look at the touches of light under the eyes and on the nose, which, in fact, really look like the work of a great painter. "It’s a very damaged painting but of great quality, even if it’s impossible to understand its original functionality: it was probably a kind of tabernacle, or something like that; it’s a figure of a Salvator Mundi thought to be seen from below, so it immediately refers to the perspective culture of the 1780s. Above all, it seems to me to be a painting of great quality. Besides that of Melozzo, the only name that came to mind was that of Pietro di Galeotto, a rather mysterious painter, whom we now know quite well, however (in Perugia, for example, there is a Flagellation of him). However, this is an artist of a lower quality, although a scholar like Bellosi wanted to attribute that Flagellation even to Bramante. The world that brings to mind this Blessing Christ is either that of Melozzo or that of the young Bramante, but of the latter we know so little that it is impossible to think of an attribution, and instead as the work of Melozzo we think mainly of the culture of the fragments of the frescoes of the Holy Apostles."

|

| Pietro di Galeotto, Flagellation, (1480; oil on canvas, 196 x 134 cm; Perugia, Oratory of San Francesco |

|

| Melozzo da Forlì, Angel Musician with Lute (c. 1480; detached fragment of fresco, from the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Rome, 101 x 70 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Vatican Picture Gallery) |

|

| Melozzo da Forlì, Ascension of Christ (c. 1480; detached fresco fragment, from the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Rome, 280 x 200 cm; Rome, Palazzo del Quirinale) |

The next step, as anticipated, will be scientific publication. “At this moment,” Gabriele Fattorini declares again, “I am studying the painting: obviously in the exhibition catalog, which will come out in a few weeks, the painting will have its own card, and then I plan to write more and present it during a day of studies that Marco Pierini is organizing for early December. There, I will explain in more detail the reasons for the attribution.” There are, however, already traces on which Fattorini’s work will be based, and which could open up unprecedented scenarios on the artist’s activity. “The painting,” the scholar concludes, “will have to be investigated as a work from the late 1970s to the 1980s in Melozzo’s Roman period: evidently he from Romagna went to Rome or returning from Rome to Romagna will have passed through Perugia and will have left here a work that did not require too much work ... and who knows for whom he made it.”

The National Gallery of Umbria, however, seems to have few doubts: the catalog for the exhibition The Other Gallery, as mentioned, has yet to come out, but the caption confidently reads “Melozzo da Forlì,” with no question marks and no acronyms such as “attr.” or the like. And the goodness of the discovery is also convinced by Marco Pierini, with whom we had the opportunity to have a word in Perugia. “The discovery of a Melozzo in the storerooms of the National Gallery of Umbria,” said the director, “is an extraordinary discovery, because not only do we acquire a work of great quality, even if in a modest state of preservation, but because it foreshadows the presence in Perugia, probably between the 1570s and 1580s, of one of the greatest painters of the Italian Renaissance. So it also opens up a whole track of research for art historians to beat in the coming years.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.