On Feb. 18 at the Palazzo dei Diamanti, the desired exhibition on the “Renaissance in Ferrara” will happily open, where the figurative arts - maximally the pictorial arts of the great masters Lorenzo Costa and Ercole de’ Roberti - will compose a world rich in culture, extraordinarily original compared to the coeval splendors that other cities-guides grasped at the golden age of Italian history. Ferrara is, as always, cradle and radiant commutator of lofty wonders! The incomparable Palazzo dei Diamanti-the most beautiful mansion in the world-has prepared its own new arrangement of reception and pathways, having equipped the rooms with the very current necessary, and hidden, equipment of every modern museum.

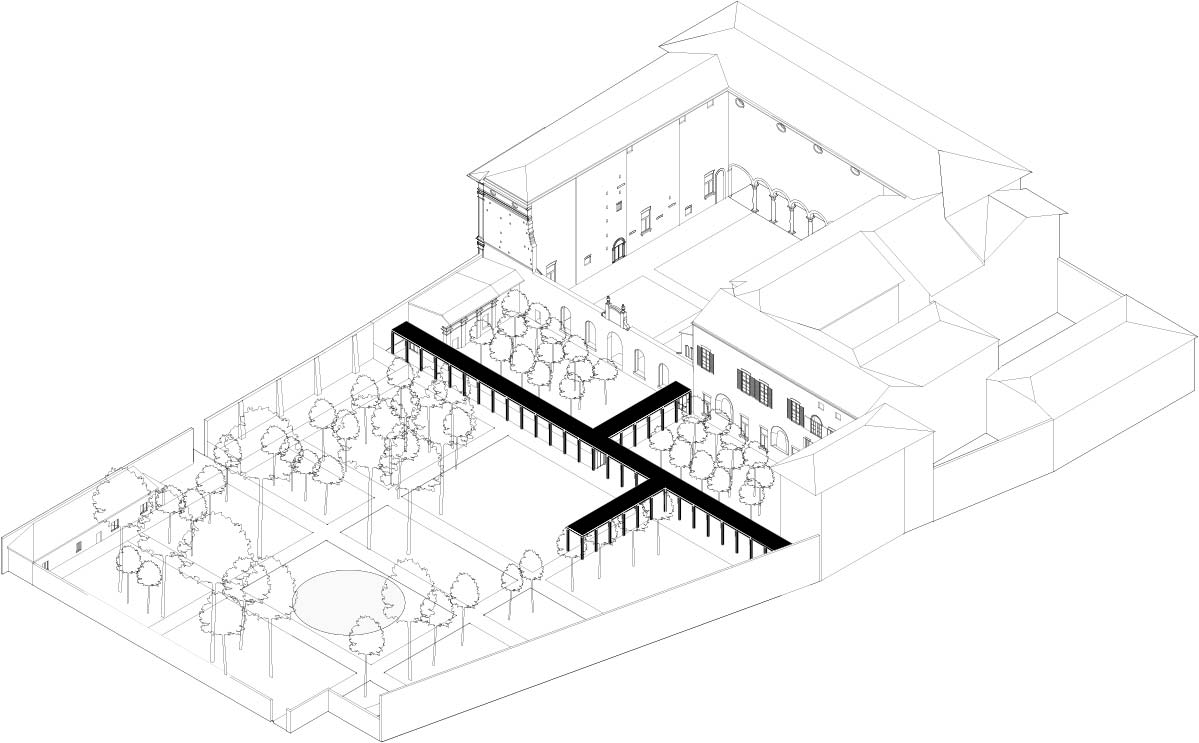

The scheme of the rational arrangement makes the Palace capable of every service and perfect logistics of routes. These include the delightful verzicante walk in the brolo

Happily, the first exhibition event makes use of an ideal female dedication: it is Portia, the most noble Roman woman realizing in herself every virtue of the Latin lineage who welcomes and invites us to the ducal city. This pre-invitation of ours that is meant to be “curiosus” does not forget the curators, Michele Danieli and Vittorio Sgarbi, as well as the valuable Press Office of Anja Rossi and the welcoming courtesy of Cristina Lago

In the names of the two artists we have mentioned, the time span targeted by the exhibition looks at the second half of the 15th century with some glimpses into the following century: the intense studies collected in the catalog and the literature that this event makes flow to the public give more reason for the essential importance of the Ferrara forge within the complexity of figurative relations, Italian and European, that touched the peculiar spirit of the very lively capital of the Po Valley within the vast cultural and social phenomena of the time. This exhibition should not be missed!

A certain preparation that we might call here “of customs and characters” can introduce you to the historical as well as chronicle scenario surrounding the work of the creative protagonists. Marquis Nicolò III d’Este (1383 - 1441) held the traditional papal investiture of the lands of Ferrara with rare political skill, passing through complex events such as the Western Schism, then serving Martin V, and even managing under Pope Condulmer (Eugene IV who was Venetian) to keep in papal hands the Polesine and the course of the Po di Maestra, whose control was economically coveted and disputed between Ferrara and the Serenissima. Two were the activities that most struck the popular imagination about the proud marquis: the construction of a large number of castles, almost all of which were vividly colored on the outside, and the tireless production of sons so much so that the saying still remembered today read “on this side and on the other side of the Po, three hundred sons of Nicolò.” Shortly before his death he designated a spurious son to the succession, and Pope Eugene accepted it. Lionello was cultured and unlearned, a classical linguist, bent on the noble life and the arts; he had relations with Venetian painters, with the very young Mantegna, with Pisanello, with Leon Battista Alberti, and with sculptors of merit. It was to his credit that the humanistic season began, and by the time of his early death (1450) he was twenty-year-old Cosmè Tura, the first great Ferrarese master who brought to Ferrara the echo of Piero della Francesca but also the imaginative severity of the northern schools.

Lionello was succeeded by his brother Borso (1413-1471), also an illegitimate son, whom Pope Nicholas V accepted, and who chose a type of life balanced between a vision of a return to the legitimate dynasty, peace over military alliances, and an almost phantasmagorical accentuation of festivals and jousting occasions, hinging on the famous “delights” that became numerous, enriched by the arts and gardens, and punctuated by games and receptions of all kinds. Borso never wanted to marry, enlarged the city and sought the favor of the people in every way: by his intervention he even went so far as to regulate the rate of widespread female services (“no more than quattrini four per dulcitudine”). He consolidated possession of the imperial fiefdoms of Modena and Reggio and procured tokens of the highest prestige such as the famous Bible, illuminated by Taddeo Crivelli and aids from 1455 to 1461-the most beautiful book in the world-which he then took to show to Pope Paul II, taking great care to bring it back. Shortly before his death he obtained from the same pope the title of Duke: a great blow to the entire dynasty, in the context of the takeover of power by another son of the indefatigable Nicolò III who, in his manly production, had also left a legitimate offspring.

During the period of Borso’s reign, the arts were widely cultivated: architecture for palaces and villas; literature with Guarino Veronese and Maria Matteo Boiardo; theater with the rising star of Nicolò da Correggio (master of delights and close friend of Leonardo); and painting with the luminous presence of Francesco del Cossa, the serene Lorenzo Costa, and the tumultuous genius of Ercole de’ Roberti. One problem with respect to the masters of color was their meager payment, so much so that they left Ferrara for Bologna. It would then be the turn of the new duke, Ercole I (1431 - 1505) to have de’ Roberti back in town to open yet another talent-rich painting season, and also to decide on the urbanistic glory of the Addizione Erculea thanks to the supernal mind of Biagio Rossetti.

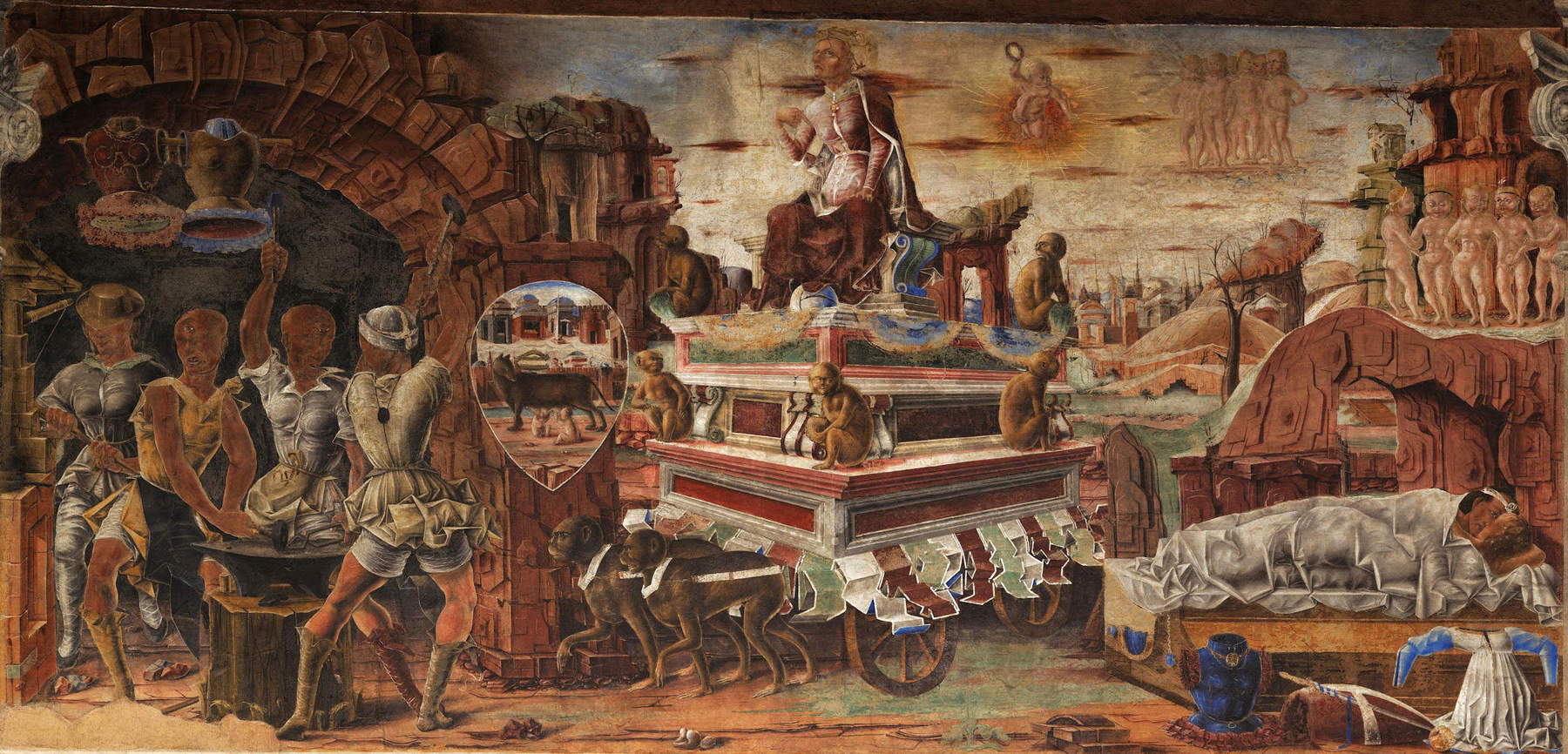

Before ideally witnessing the moment of the fugitive painters, it is good to dwell on the last fresco of Ercole de’ Roberti’s early phase when the dashing young man painted the Mese di Settembre at Schifanoia (1470). We must therefore recommend that the wise visitor to the exhibition culturally pick up the enjoyment of the vaunted urban “delight” to rightly place it within the continuity of the fascinating artistic expansion that took place in the heart of Ferrara’s Renaissance season. The “month of September” appears as a thundering, bewildering whirlwind that brings together myth and alchemy, cryptic symbolism and sensuality in action, dynastic ambitions and fabrial necessities; all against the backdrop of a “rising city” and fiery celestial favors. On the chariot stands Vulcan-mythically the ugly god who was fed by apes, but as necessary as an artificer-who appears effeminate in that he is inflamed with love, and even such is seen in the workshop where with the serving Cyclopes he prepares Aeneas’ weapons. The shield of the Trojan hero glows in the center carrying the suckling she-wolf and the two little twins who will begin the Roman lineage: a blood hook for the Este family who had lofty ambitions. And on the thalamus below, among the stigmata rocks to usbergo, Venus’ thanksgiving to her despised husband who finally wins the “semper optatus amplexus.”

Everything here is angular since our Hercules-pictor launches himself into a dissolved contest with the great Cosmè, as the last entanglement in an atmosphere of armigerous dispute that by now Boiardo posed in his timbral verses.

After his commitments in Schifanoia, Francesco del Cossa settled permanently in Bologna, where he would find honors and important commissions, and where he died at the age of 42 in 1478. He was followed in the city of Bologna by Ercole as a faithful colleague, who was to complete some masterpieces of the highest caliber: we recall the Griffoni Polyptych and above all the astonishing Garganelli Chapel in St. Peter’s, which Michelangelo judged to be of value “equal to half of Rome.” In Bologna, de’ Roberti will acquire confidence in composition, timbral fortitude in colors, general clarity of classical observance. We can already feel the characters in the impressive predella of the Griffoni Polyptych (27.5 x 257 cm) where the complexity of the color composition continually confrica of shudders between canonical architecture and the poetics of ruins on many planes, tricking the figures into polemical glimpses. From the Garganelli walls we are left, as is well known, with the unforgettable head of the weeping Magdalene, which alone - to refer the verse back to Buonarroti - soars us in plenitude over the entire universe of the sacred and lost poem of Hercules.

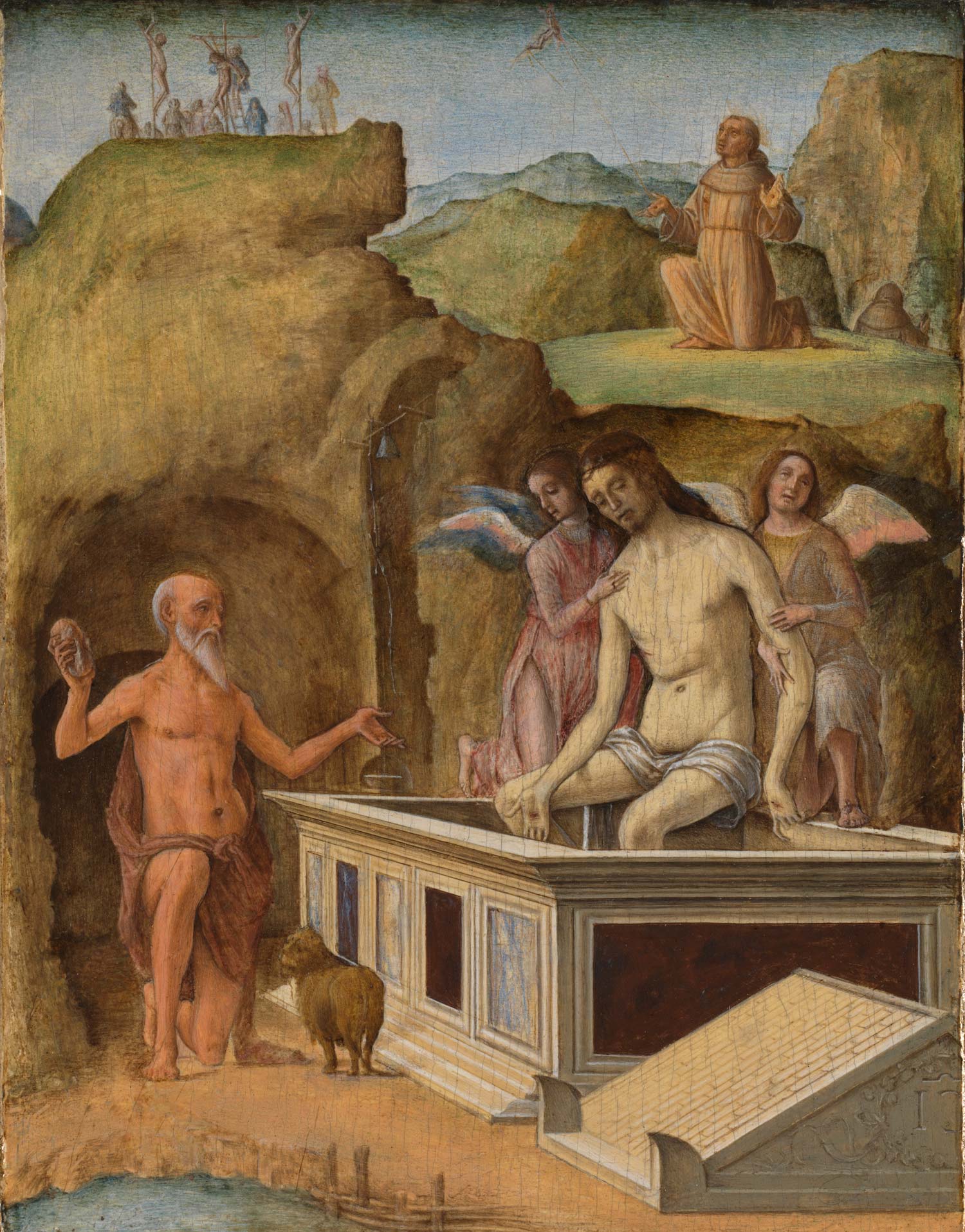

In the last decade of his life, de’ Roberti returned to the court of the Dukes of Ferrara, and for the Este family he fulfilled various tasks, including that of a trusted family man. He continued, however, to paint portraits and mainly religious subjects. The exhibition follows him closely as he, who will die not yet 50, gathers all the experiences of the great masters of his century, arriving at a synthesis of meditative depth and intimate relationship of the light-color phenomenon. In this way the prevalence of the clear Venetian sky is reconciled with the atmospheric experiences already indicated by Leonardo, which here in the Po Valley humidors become contemplative thicknesses and a reason for the balance achieved: almost immutable realm of the soul. In this sense are certainly to be read the Adoration of the Shepherds, and the enveloping mysticism of the Vision of St. Jerome with the Reception of the Stigmata of St. Francis, both now in London. On the other hand, the delightful Berlin Madonna can still be a source, by itself, of ineffable spiritual commingling with the clear-hearted observer. Ercole de’ Roberti’s eloquence then achieves the fulfillment that all fifteenth-century Ferrara painting had feverishly sought on sonorous, extroverted, expansive lines.

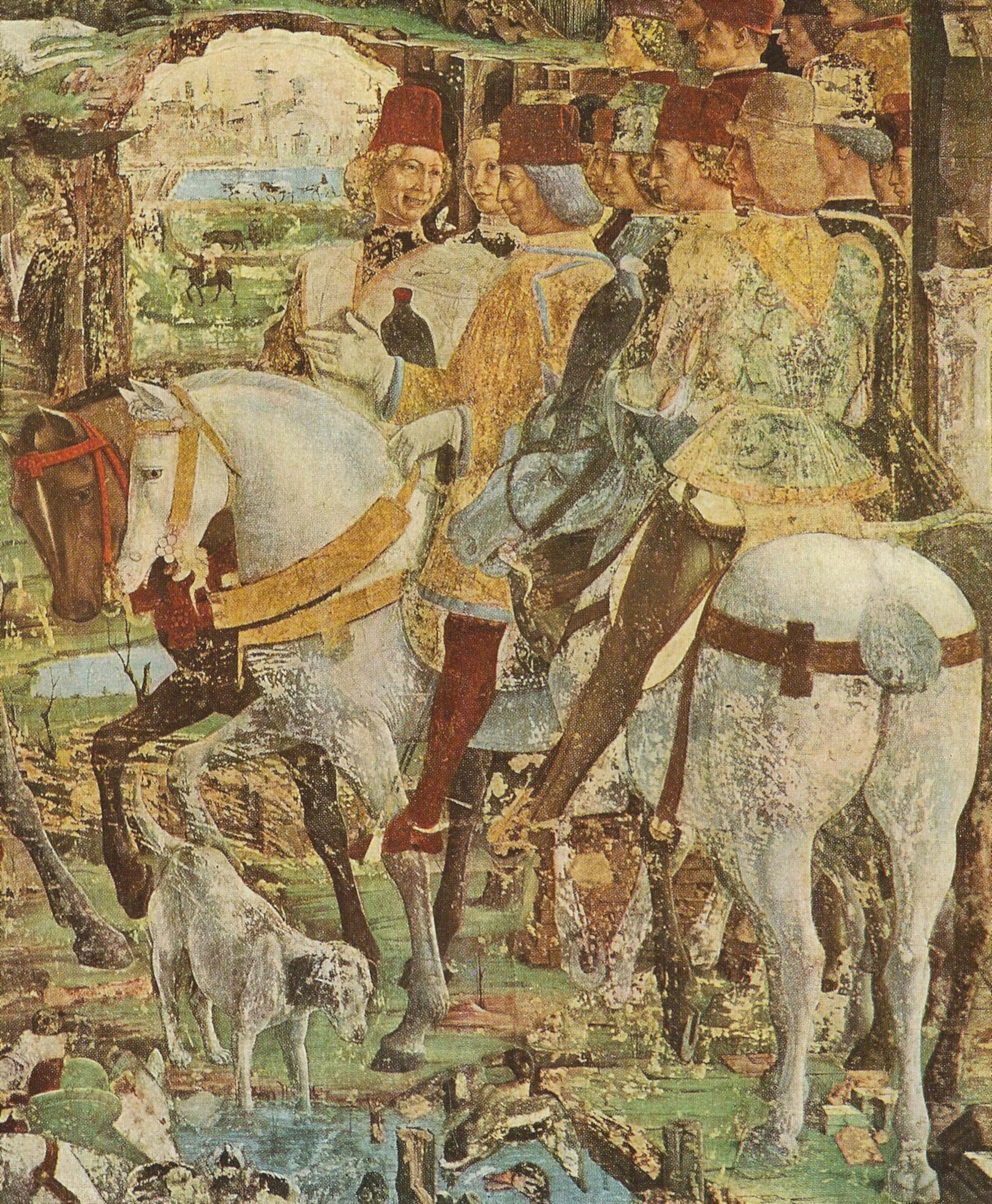

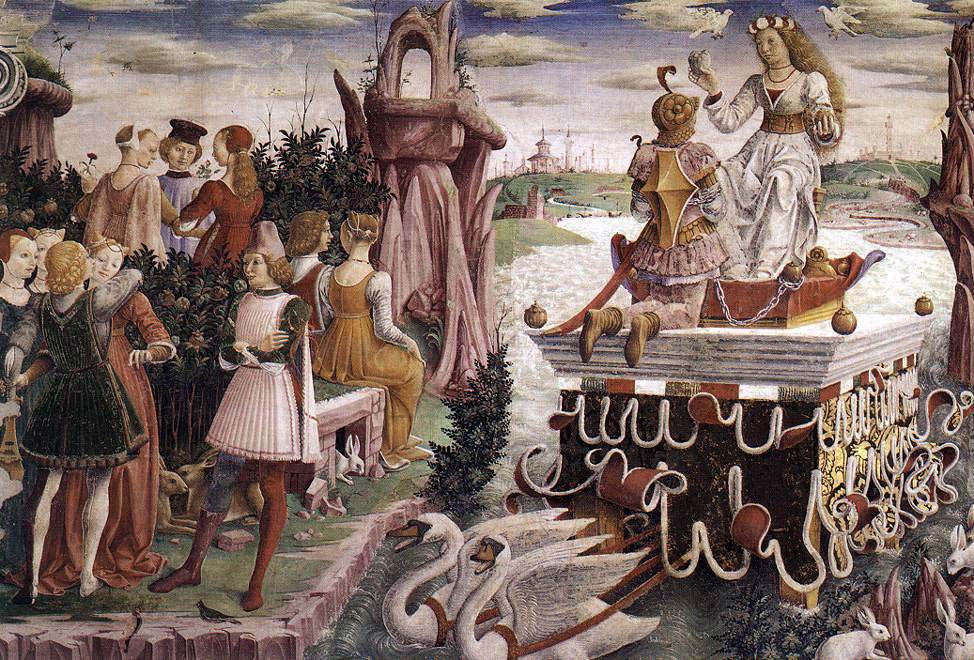

The personality of Lorenzo Costa (Ferrara, c. 1460 - Mantua, 1535) dominates the Renaissance of the Po Valley in a broad sense: inclined to be “always restlessly experimental” (Benati) he introduces himself to painting on the civic examples of Cossa and de’ Roberti but soon leaves for Florence and here absorbs the composure and clareness of Benozzo Gozzoli. Then in 1483 he moved to Bologna where he came to enjoy the full esteem of the Bentivoglio family for whom he worked for a long time balancing himself between the courtly Francia and the infrenate Aspertini, but remaining attentive to the Venetian conquests and the new magnificent manner of the Florence-Rome axis.

A sign of Costa’s versatility in the Bologna years, where he would produce himself with a truly notable range of expression, are the mythological plates dated around 1483 and dedicated to the exploits of the Argonauts as a scenic tale.

Lorenzo, who at the fall of the Bentivoglio family (1506) went to Mantua at the insistent invitation of Isabella d’Este Gonzaga, was not, however, a wavering artist or epigone, but a skillful builder of his personality in the field of painting up to the harmonious development in excellent terms of his manner, as will be fully grasped in the exhibition. Costa therefore was the true heir of Ercole de’ Roberti giving his own language a “very strong acceleration” and bringing it to the threshold of modernity.

We can recall the accomplishment of the great protagonist of the Ferrara Renaissance in the canvases of Isabella’s Studiolo in Mantua, but also in the other movable paintings that a patronage of rank requested of him, aiming finally at a portrait: a genre that tests every figurative artist and imposes on him a particular interpretative commitment. Here, too, Our Lord determines success by clearly bringing the effigy closer to the visual picture, endowing it with the appropriate attributes, but giving us the double space in the open air where elevating penance to God and the life-giving breath of nature coexist.

The conclusion of this invitation we can fulfill with the vision of the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Andrea Forlani’s beautiful photograph, placing ourselves under the marvelous historiated pilaster and the pungent corner balcony, a true directional invitation toward the ducal delights and the open sea.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.